Teaching policy analysis is a demanding and rewarding task for an instructor. The concepts and their application are challenging; however, when students master policy analysis, they gain a crucial tool for diagnosing and addressing society’s most complex policy problems. During a full semester, instructors teach students the concepts needed to understand the policy analysis process, engage in primary research, and critically analyze problems and possible solutions in applied projects. In this flood of concepts and application, students can default to memorizing terms and gathering source after source rather than critically applying the concepts to define problems or select appropriate criteria. As Bardach (Reference Bardach2011, 12–13) pointed out, students often focus on gathering evidence to the detriment of thinking “because running around collecting data looks and feels productive, whereas first-rate thinking is hard and frustrating.” How do we encourage students to focus on thinking rather than on memorization and data gathering?

Our solution is for students to perform an initial policy analysis based on an assigned film before completing an applied policy analysis later in the semester. This two-step assignment structure supports key pedagogical objectives within the resource constraints of a full semester. As Bardach (Reference Bardach2011, 11) wrote, “Policy analysis is spent in two activities: thinking and hustling data that can be turned into evidence. Of these two activities, thinking is by far more important, but hustling data takes much more time.” In a film-based policy analysis, students identify and analyze policy problems in a film without referencing outside resources. This practice focuses student effort on thinking rather than on data collection for the first assignment of the semester. Students then devote time and attention to specifically developing the multiple cognitive processes necessary for analytical work. Bloom’s (Reference Bloom1956) taxonomy outlines the six cognitive steps necessary for higher-order thinking: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. In the film assignment, students demonstrate knowledge and comprehension of the foundational concepts and procedures used in policy analysis. When this base is established, students then develop the remaining higher-order thinking skills in Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Krathwohl, Airasian, Cruikshank, Mayer and Pintrich2000). By definition, policy analysis involves both application and analysis. In addition, students must make evaluative judgments at multiple stages in the assignment, which are discussed later in this article. Finally, the written product involves the creation of a coherent report that synthesizes the component parts, reasoning process, and final recommendations. Deliberate emphasis on the cognitive processes involved in policy analysis, combined with the research skills learned in the second assignment, equips students with the skills that faculty and employers know matter in the policy realm (Castillo Reference Castillo2014).

Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy outlines the six cognitive steps necessary for higher-order thinking: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. In the film assignment, students demonstrate knowledge and comprehension of the foundational concepts and procedures used in policy analysis.

Students benefit from the two-step structure of the film and applied assignments because the film assignment explicitly engages them in the fundamental tasks of policy analysis, but it limits the amount of new material they must master. The film analysis effectively isolates the research and outcome-projection sections of policy analysis for emphasis in the applied project later in the semester. Therefore, student time and instructor feedback early in the semester is devoted to developing what Bardach termed “first-rate thinking” (Reference Bardach2011, 12). Because the assignment is explicitly framed as an exercise focused on thinking, it communicates to students the importance of the higher-order cognitive processes that undergird high-quality analyses. Concentrating attention on logical thought processes builds a strong foundation for further training in policy analysis. Instructors can focus on facilitating the development of analytical and evaluative thinking rather than spend time checking sources, rerunning calculations, and guiding student research. The film assignment, therefore, has many of the same benefits of “mini-projects” at the beginning of the semester advocated by Vining and Weimer (Reference Vining and Weimer2002) in their sheltered-workshop approach. In the mini-projects, as in the film analysis, students are isolated from the idiosyncratic demands of complex applied projects and instead focus on learning and integrating the core skills of policy analysis. At the same time, giving the assignment a low weight in the grading schema provides an opportunity for low-stakes feedback early in the semester. This early feedback maximizes opportunities for growth, learning, and excellence in the applied project (Boice Reference Boice2000).

In addition to pedagogical benefits, a film-based analysis has practical benefits for both students and faculty. First, faculty members receive better work products in both the film and applied assignments because students focus on separate skills in separate assignments. This makes grading considerably more enjoyable. Second, the assignment provides a high ratio of pedagogical “bang” for grading “buck.” Applied analyses are challenging to supervise and grade because instructors must learn enough about the topic to judge student performance and provide feedback. Even a relatively focused set of student topics can quickly become overwhelming. For example, grading and providing feedback on a set of assignments on the shared-economy might require that instructors understand the intricacies of zoning, inspection and property-tax policies (e.g., AirBnB), taxi and limousine regulation and automobile insurance (e.g., Uber), and local sales and use taxes (e.g., SnapGoods). Doing this once in a semester is difficult; twice in the course of a semester can be overwhelming.

SELECTING FILMS TO MAXIMIZE LEARNING

A film-based assignment functions best when students view films that challenge them to identify policy problems but do not explicitly define them. Selecting movies that meet this objective can be difficult. Most documentaries and many feature films are created with a specific problem definition in mind. For example, Guggenheim’s (Reference Guggenheim2010) Waiting for “Superman” uses personal vignettes of students entering lotteries for charter-school slots to highlight equity issues in education around the country. However, assigning this movie as the subject of a policy analysis is not particularly useful. Guggenheim already framed the problem (i.e., poor public schools) and is implicitly framing the criteria by which it should be judged (i.e., equity and fairness of lottery systems). A policy analysis of this film would be simply a book review. Many feature films are similarly constructed. For example, the film Erin Brockovich (Soderbergh Reference Soderbergh2000) explicitly frames environmental problems and identifies the stakeholders involved.

Animated films are a useful alternative for several reasons. First, students initially enjoy them because they bring a lighthearted moment to a course about society’s unsolved (and often unsolvable) problems. Second, in contrast to documentaries, the primary conflict in animated films is typically a relational conflict among several main characters. Animated films are structured this way because children are unable to think abstractly about larger issues. This prevents the central conflict in the film from being framed systemically. After students finish watching an animated film, they are left with an enjoyable experience but a film in which policy problems lurk in the background and remain undefined. Where is government involved in the story? Is there a market failure present? Are equity issues at stake? Animated films therefore force students to identify and make judgments about which public-policy problems are present. Third, in contrast to animated films, nonanimated films often invoke real policy problems; students begin to focus on understanding the facts and figures of the particular context rather than the first-rate thinking that the assignment is designed to encourage.

Although there are solid pedagogical reasons for using animated films, some students and instructors may think that using them trivializes the important work performed by policy analysts. Most of the pedagogical benefits of the assignment can be realized using non-animated films. For example, the assignment can be adapted to offer students a choice of animated or non-animated films or to eliminate the animated films entirely. In previous semesters, we offered Good Will Hunting (Van Sant Reference Van Sant1998) as a choice for students. Footnote 1 The story line focuses on the personal growth of the lead character, but multiple social issues are evident in the film and provide opportunities for analysis. After experimenting with both types of films, we settled on animated films for our classes. In our experience, the more that a film mirrors real life, the more students rely on common politically acceptable solutions and technically feasible policy alternatives. Students tend to default to the standard rhetoric and dominant perspectives surrounding an issue without exploring transformative policy options. Learning still occurs, but we have found that the divide blurs between focusing on “first-rate thinking” in the film assignment and research in the applied assignment. That said, whichever genre is chosen, the use of non-documentary feature films provides a powerful complement to other class assignments. The most important learning objective—to focus on and improve evaluative thinking—is served.

THE ASSIGNMENT: APPLYING THE STEPS OF POLICY ANALYSIS

For the film-based policy analysis, students are randomly assigned a specific movie or offered a choice of several movies to watch. After the students view the movies, they walk through the steps of the policy-analysis process and execute them using the movie as the situational context. Footnote 2 In our courses, we use Bardach (Reference Bardach2011) and Weimer and Vining (Reference Weimer and Vining2011) as primary texts. The assignment follows five broad steps of policy analysis: defining the problem, establishing criteria, developing alternatives, conducting the assessment, and making a recommendation. Learning objectives in the assignment, however, include developing proficiency in the specific eight steps outlined by Bardach which provide further elaboration on policy analysis tasks. Students are expected to produce a concise written report of the analysis, which is the basis for their grade. Those who analyze the same movie may be grouped together in class for comparative discussion to further facilitate learning. Doing so can be used to focus discussion on a particular step of policy analysis. After their papers are submitted, students take time in class to discuss with others who viewed the same movie which problems they identified or solutions they generated. For example, they may debate and justify whether their problem definitions are clear and whether they warrant government intervention. Recognizing that other people viewed the same film and identified different policy problems helps students to understand that problem definition is more complex and challenging than they initially may believe.

For the purposes of this article, we outline how this exercise would be used to follow Bardach’s eight steps analyzing the film Ratatouille (Bird and Pinkava Reference Bird and Pinkava2007), which is a coming-of-age movie about love, grumpy authority figures, and cooking in a Parisian restaurant. A young dishwasher tries to save his father’s restaurant and win the heart of a young chef by learning how to cook. The fantastical part of the story is that a rat with gourmet tastes controls the dishwasher’s actions in the kitchen, thereby transforming him into a master chef. In the end, a food critic must decide whether the food is sufficiently excellent to overcome the stigma of rats cooking it and to keep the restaurant open.

Step 1: Defining the Problem

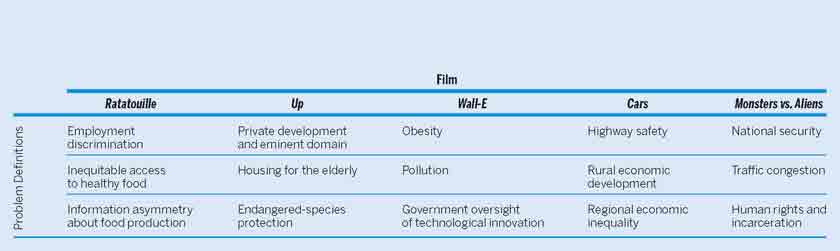

First, students are asked to identify and describe a policy problem presented in their movie. Because animated films are framed as a relational tale among the main characters, students must begin by asking, “Where is the public-policy problem?” For Ratatouille, students identified various public-policy problems lurking in the background. One student decided that because the clientele of the restaurant did not know that rats prepared the food, there was an information asymmetry. Customers assumed that they knew who prepared the food, but the producer knew differently. A second student decided that favoring human over rat employees constituted employment discrimination. A third student claimed that because rats were banned from eating at the restaurant, people and rats had inequitable access to healthy food. Table 1 lists these and other examples from selected animated movies. None of the problems is explicitly depicted in the movies. The plots revolve around characters, but public-policy issues exist in the background. For this step, students must demonstrate that they understand when government intervention is appropriate and make the case for it by using evaluative thinking.

Table 1 Animated Films and Sample Public-Policy Problems Identified by Students

Step 2: Assembling Evidence

Assembling evidence about the scope and background of the problem is time-consuming. Gathering information is also required to consider feasible solutions and conduct an assessment in later stages of policy analysis. These tasks are what render client-based policy analyses impractical in many compressed time frames. Assembling evidence requires its own art. Footnote 3 This necessary skill is best developed with an appreciation for effective strategies in conducting high-quality research. As Bardach (Reference Bardach2011, 12–13) stated, “The principle—and exceedingly common—mistake made by beginners and veterans alike is to spend time collecting data that have little or no potential to be developed into evidence concerning anything you actually care about.” Technology makes it easy for students to default to poor information-gathering strategies, which further contributes to the wealth of low-quality information students sometimes use to support their analyses. The most readily available research found in an Internet search may not be relevant or credible.

External research is prohibited for this assignment, which allows for a quick turnaround time and initial feedback to students. However, students are expected to suggest evidence—whether theoretical, empirical, or expert opinion—that would support their claims. Student papers that suggest an information asymmetry between food producers and consumers in Ratatouille indicate an awareness of economic theory as a resource for theoretical support for their arguments. Another student might suggest that the latest Paris Department of Labor reports indicate a certain number of discrimination complaints filed by rats seeking jobs. The reasoning relies on assessments about the type of information that would be relevant and appropriate in the analysis. This deliberately reflective exercise forces students to “think and keep on thinking about what you do and don’t need to know and why” (Bardach Reference Bardach2011, 12), thereby training them to be efficient data collectors in future analyses rooted in real-world contextualized problems. Footnote 4

To solve the public-policy problem they identified, students must understand which tools are available to policy makers and then logically connect them to their problem definition.

Step 3: Constructing Alternatives

To solve the public-policy problem they identified, students must understand which tools are available to policy makers and then logically connect them to their problem definition. Footnote 5 Students often wrestle with creating alternatives that logically follow from their specific problem definition and instead immediately focus on feasible or common solutions. This exercise requires students to think creatively and logically to apply appropriate policy tools to a specific problem. A pedagogically helpful aspect of the film assignment is that students are willing to consider alternatives that are too politically incorrect to bring up when discussing real-life examples. For example, a student who defined the problem in Ratatouille as unequal access to quality food gave three alternatives: (1) rats steal food from restaurants that make no accommodation to allow them access to food; (2) rats work as kitchen staff in exchange for food; and (3) rats and humans are served the same food at segregated restaurants. These options are logically connected to the student’s problem definition despite the fact that options (1) and (3) are infeasible in their real-world parallels. Separate-but-equal facilities for rats and humans will emerge as a policy alternative in this setting; however, it has almost no chance of being considered an option in a discussion of racial discrimination in the United States. Without being constrained by socially acceptable or popular solutions evident in real-world debates, students focus their evaluative thinking on the relationships among specific problems, their causes, and the corresponding solutions.

Step 4: Select Criteria

Bardach’s fourth step is constructing criteria by which to choose among the alternatives. Students often struggle to choose relevant criteria and to develop concrete indicators that are amenable and useful in selecting among the alternatives. Textbooks often include lists of commonly used criteria such as efficiency, equity, liberty, and political feasibility. Students may readily choose some from the list that are correct and helpful, but this assignment requires them to offer reasoning for their choice of particular criteria. They are urged to specifically confront the normative nature of policy analysis in choosing which qualities attach worth or value to possible policy solutions. What makes one policy good or better than another? In our experience, the greatest challenge for students is adapting conceptual criteria to concrete and useful measures regarding a particular social issue. Students may correctly identify equity as an important criterion in addressing the Ratatouille problems of employment discrimination and access to healthy food. However, further thought must be given to defining that concept in an operational form. Access to healthy food may be measured in terms of the number of accessible restaurants or stores or the overall quantity of food options available, regardless of the delivery mechanism.

Step 5: Projecting Outcomes

The fifth step is to project outcomes. As Bardach (Reference Bardach2011, 47) stated, this is “the hardest step” of policy analysis because of the massive uncertainties inherent in predicting the future. Although students cannot practice forecasting or calculating possible outcomes, the assignment requires careful deliberation about likely outcomes. They must offer some basis or explanation for their projections, which forces them to examine the assumptions inherent in their solutions. Would rats want to work in the food industry to either gain employment or provide access to healthier food? What is the likelihood that rats would be punished for stealing food? How many rats would be willing to risk such punishment? Making assumptions explicit is required when projecting outcomes, whether extrapolating projections from empirical evidence or simply using logical arguments.

Step 6: Confronting Tradeoffs

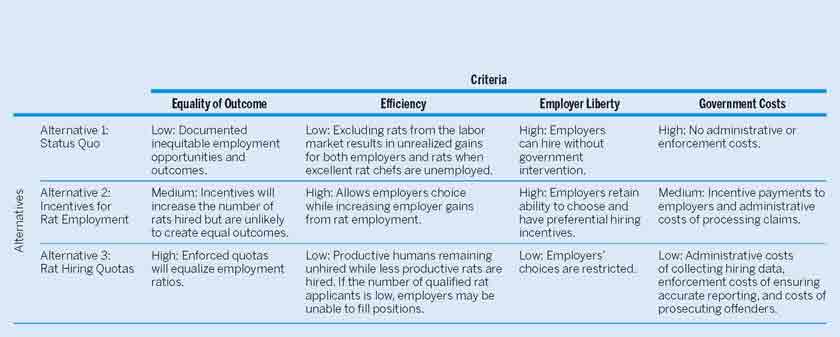

The sixth step is to confront the tradeoffs among the alternatives. Here, a decision matrix is a helpful tool (MacRae and Whittington Reference MacRae and Whittington1997). Table 2 represents one student’s example. Students often struggle to create their criteria–alternatives matrix. Footnote 6 Although this may seem basic given the work already accomplished in the analysis, this step helps them to synthesize their findings and produce a concise product focused on prioritized information. Their first attempts often omit crucial points or include too much information. We emphasize to students the limited time that policy makers have to read an analysis and how frequently they will turn directly to a table as a summary of the document. Every word counts. The decision matrix also forces students to systematically compare and evaluate the alternatives based on the criteria rather than choose which one is easiest to explain or represents their favorite option. Rarely does one alternative dominate on every criterion, so they must determine and defend their weighting of criteria and corresponding choices.

Table 2 Example Alternatives–Criteria Matrix for Employment Discrimination in Ratatouille

Steps 7 and 8: Deciding and Telling the Story

The seventh and eighth steps are to make a recommendation and to tell the story. If the matrix has been completed satisfactorily, the recommendation should immediately flow from the analysis and evaluation inherent in projecting outcomes and confronting tradeoffs. Students practice telling their analytical story in a format that busy policy makers can read rather than in a traditional academic paper, which is an important skill (Pennock Reference Pennock2011). Learning to write an executive summary, formatting the document in a way that makes it easy to skim and understand, and writing clearly are all practiced in this exercise. With such a tight page limit, students must determine the most important ideas and words to include. A common mistake of students—despite the weight given to each section in the grading rubric—is to spend considerable time on the movie synopsis rather than the analytical arguments.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a film-based policy analysis helps instructors to meet many of their pedagogical goals while simultaneously addressing the time and resource constraints they face in managing client-based projects or other preparation-intensive alternatives (e.g., simulations and case studies). Students are required to think critically through every step of the policy-analysis process. Whether in defining the problem or determining appropriate criteria, students must demonstrate deliberative judgment and assessment. The concentrated attention given to the thinking processes, apart from time-consuming research tasks, supports key pedagogical objectives and trains students for work in the policy world. The use of animated films, in particular, ensures that the problem is not already explicitly framed for students and also provides a brief respite in a semester replete with serious and complex social problems. Using the assignment as an introduction to policy analysis with an additional follow-up assignment affords the opportunity to ensure that students have the necessary knowledge and comprehension of key theoretical frameworks before conducting an applied policy analysis.

We offer the film-based analysis exercise as an additional teaching tool to complement existing strategies. In our classes, it has proven to be an effective strategy to orient students to the steps of policy analysis, to review student skills and preexisting knowledge to modify the semester course plan, and to facilitate higher-order thinking necessary for conducting policy analysis. Given the low time investment, the pedagogical yields are high.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the editors, three anonymous reviewers, and participants at the 2014 Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Spring Conference for comments and suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript.