In today's information age, obtaining facts is hardly a challenge. In fact, students are surrounded by information: Through online databases, books, articles, newspapers, and more recently through websites, blogs, and social networking interfaces, students have access to unprecedented amounts of information without ever leaving their study rooms. What remains a challenge, however, is the development of the skills that are needed to critique and process this easy-to-obtain information. Critical thinking is described variously, as “the capacity to work with complex ideas whereby a person can make effective provision of evidence to justify a reasonable judgement,” as “the shift of learners from absolute conceptions of knowledge towards contextual knowing” and as “an understanding of knowledge as constructed and related to its context” (Moon Reference Moon2008, 128).Footnote 1 Previous research demonstrated that critical thinking skills can be developed through a number of activities, including simulation, optical illusion exercise (Hoefler Reference Hoefler1994), statistical data analysis (McBride Reference McBride1996), classroom debates and guest speakers (Cohen Reference Cohen1993), multiple, short exercises (Atwater Reference Atwater1991), analysis briefs (Alex-Assensoh Reference Alex-Assensoh2008), and electronic discussions (Greenlaw and DeLoach Reference Greenlaw and DeLoach2003). In the political science classroom, writing assignments and their potential contribution to the development of these skills receive relatively less attention than in other disciplines. A two-stage writing assignment, described in this article, may be an effective way to teach undergraduate students these skills.

We particularly focus on writing assignments for two reasons: First, writing, as “thought on paper,”Footnote 2 can provide a unique opportunity to develop critical thinking skills, and second, our experience with writing assignments is commonly shared among faculty from across the disciplines. Students rarely pay attention to the feedback that instructors give on graded papers that leads to student repetition of the same mistakes. We advocate a carefully designed writing assignment that provides not only a unique opportunity for students to hone their critical thinking skills, but also provides students with incentive to pay attention to an instructor's feedback. The assignment, used in an introductory level comparative politics course, requires students to apply abstract theories to concrete cases and consists of two papers: a draft and a final. Although essentially asking the same question as in the draft paper, the final paper requires far more than simple editing, which is a common and limited revision practice among novice academic writers (Sommers Reference Sommers1980). Instead, the final paper instructions set higher standards and require additional steps. These steps include students conducting research to incorporate additional sources into the revision and writing a postscript that reflects on their learning processes. In this article, we describe the rationale, objectives, and stages of this writing assignment; explain its rubric; and provide sample paragraphs and postscripts written by students.

DEVELOPING STUDENTS' CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS

Critical thinking involves a set of strategies to help students develop reflective analysis and evaluation of interpretations or explanations, including one's own, to decide what to believe or what to do (Fisher Reference Fisher2001). It assumes an inquiry and hypothesis-based approach to ideas as well as thinking that is open to revision. Despite associations with negativity or mere complaint, critical thinking actually focuses on the rational and demonstrable. Associated with higher-order thinking, critical thinking involves “knowledge transformation” (Scardamalia and Bereiter Reference Scardamalia, Bereiter and Rosenberg1987) rather than the kind of knowledge-telling associated with production of lists or other memorized recitals of information. As such, critical thinking skills are among those that undergraduates are expected to master during their college education, regardless of discipline (Greenlaw and DeLoach Reference Greenlaw and DeLoach2003).

Acquiring critical thinking skills requires intellectual self-discipline that produces skillful and reflexive thinking. Of the many critical thinking instruments available for measuring critical thinking in college students, we chose the most traditional and commonly used Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal to develop our two-stage writing assignment.Footnote 3 The Watson-Glaser Appraisal identifies five levels of intellectual activity that are essential to critical thinking:

1. Inference: The ability to derive logical conclusions from the premises of varied approaches.

2. Recognition of Assumptions: The ability to recognize assumptions and presuppositions implicit in the approaches.

3. Deductions: The ability to judge whether propositions made by the approaches can be logically drawn from the evidence.

4. Interpretation: The ability to judge whether the conclusions and arguments made by the approaches can be logically drawn.

5. Evaluation of Arguments: The ability to distinguish relevant, strong, and weak arguments.

As this instrument suggests, critical thinkers engage in inferential analysis and in both recognition and evaluation of differing approaches and perspectives. Critical thinkers also demonstrate the ability to tease out the assumptions of the varied approaches and then stake an informed claim or make a judgment about the approaches based on available information and a deliberate process that is both analytic and synthetic. At the same time, critical thinkers also recognize that their claims are provisional or subject to revision based on new information. Obtaining these skills is important for college students, in general, and political science students, in particular: Specifically, the political science lower-division undergraduate must acquire these skills to evaluate texts, assess media reports, and construct better arguments, among the many central objectives of the political science curriculum. In short, college students need to develop these skills to think, write, and communicate effectively.

WRITING IS CRUCIAL IN CULTIVATING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS

We have long heard about the declining writing skills of students, a predicament periodically documented in the reports and statistics of public and nonprofit educational institutions alike, such as the Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences, The Consortium for the Study of Writing in College, and the National Commission on Writing in America's Schools and Colleges (Addison and McGee Reference Addison and McGee2010; Baglione Reference Baglione2008). These reports confirm what the education, business, and policy-making circles have long articulated, which is that “the quality of writing must be improved if students are to succeed in college and in life” (The National Commission on Writing 2003, 7). Despite its articulated importance over the past years, however, the quality of writing continues to pose significant challenges to educators. In a political science classroom, students' poor writing skills are revealed in a number of ways. These include such problems as

1. Weakly constructed and substantiated arguments

2. Less-than-careful reading of the instructions

3. Lack of precision

4. Lack of a clear and sustained line of thought

5. Difficulty with utilizing evidence to substantiate or challenge an argument

6. Weak or absent evaluation of the assumptions of the theory at hand

7. Lack of organized, convincing, rich, and elaborate responses to the question at hand

8. An inability or unwillingness to integrate the feedback that instructors provide on drafts

The act of writing, by itself, however, may offer an important opportunity for learning. In fact, writing has been posited as a unique mode of learning (Emig Reference Emig1977). Case studies and student self-reports also suggest that writing is among the strategies students find most helpful to develop critical thinking skills (Tsui Reference Tsui1999, Reference Tsui2002). Furthermore, research in disciplinary writing suggests the potency of the so-called write-to-learn tradition as a subset of the writing-across-the-curriculum movement (McLeod Reference McLeod1987). This pedagogical tradition has been recently updated through comprehensive sets of direct instructional strategies, which rely heavily on writing (Bean Reference Bean2011). As the National Commission on Writing's (NCW) report (2006) emphasized, “Writing is not simply a way for students to demonstrate what they know. It is a way to help them understand what they know. At its best, writing is learning” (51). As a result, “Writing is so essential to learning” that “one cannot be educated and yet unable to communicate one's ideas in writing form” (Paul and Elder Reference Paul and Elder2007, 4).

Traditional, formal, or “high stakes” (Elbow Reference Elbow, Sorcinelli and Elbow1997) writing assignments often fall short in addressing the aforementioned problems in the college students' writing; assignments often also fail to help students develop critical thinking skills. In a traditional writing assignment, students are expected to demonstrate the knowledge and skills that they have acquired either in class or on their own. Instructors grade the assignments, providing feedback that identifies strengths and weaknesses, and expect students to reflect on the responses and incorporate the feedback into their subsequent writing. This expected communication between the instructor and the student, however, often does not occur for several reasons, not least of which is that students are often not offered an immediate opportunity to apply new knowledge gleaned from the feedback. In other words, when revision is not allowed or encouraged, student improvement is less likely. Simple failures of communication both by the instructor and the student during the feedback loop can further hinder student improvement (Hodges Reference Hodges, Sorcinelli and Elbow1997; Lunsford Reference Lunsford, Sorcinelli and Elbow1997; Sommers Reference Sommers1982; Underwood and Tregidgo Reference Underwood and Tregidgo2006). As a result, many of the challenges we see in the writing of introductory-level students are repeated again and again when they write for upper-division courses.

The paired assignments we posit here reflect careful assignment design using staging and scaffolding of writing assignments, both of which provide opportunity for meaningful feedback and student demonstration of improved thinking, writing, and learning. Feedback loops build opportunities for communication between the student and instructor during the development of writing, rather than only as evaluative information provided after an assignment is finished and graded. Such loops facilitate both the learning content and writing improvement. Scaffolded writing assignments, defined as progressive assignments that build increasingly complex skill sets, also provide tangible demonstration of improved performance of thinking and writing—in our case the construction of more sophisticated argumentation through the use of external sources.

Our design further extends the writing assignment beyond the formal performance of writing to also include a postscript or memo that provides students with space for reflection, self-assessment, and meta-cognition. This approach taps into both declarative and procedural knowledge (Anderson Reference Anderson1976), which is the notion that students are often able to articulate or declare their writing intentions before they are able to apply or demonstrate these at a satisfactory level, a phenomenon repeated throughout human performance. This performance difference, between what is intended and what is achieved, is a productive space consistent with Vygotsky's (Reference Vygotsky1978) notion of the “zone of proximal development” or the optimal area for learning. As detailed in the following text, a carefully crafted writing assignment, like the one we propose, can set the conditions for student engagement and enhanced learning opportunities.

PREPARING A TWO-STAGE WRITING ASSIGNMENT WITH POSTSCRIPT

The writing assignment we posit here integrates critical thinking thanks to a recursive writing process. Here, meaning undergoes accretion and refinement as a result of the student's revision process. This approach challenges simple linear processing and the common student belief that after the paper is turned in, the thinking is over, the job is done. The assignment, instead, consists of two papers, a draft (table 1) and a final (table 2). In the first stage of the assignment (Paper I), students must write a paper addressing the question as illustrated in column 1 of table 1, specifics of which are described in column 2. Column 3 and column 4 of table 1 provide lists of style requirements and the objectives of the assignment, respectively. The question requires students to examine the question of health care in the United States, from the perspectives of two political ideologies, namely liberalism and social democracy. Specifically, students are asked to identify and evaluate the solutions of these ideologies to the health-care challenge in the United States. Although this question may not seem especially challenging at the outset, note that neither the United States as a case study, nor health care as a topic, is discussed anywhere in the course or textbook. Asking that ideology be applied to a novel topic and an uncovered case is intentional; it aims to engage students in thinking without influence from specific material covered in class or by the textbook. For this assignment, simple recitation or recycling of classroom notes is therefore inadequate, while application of ideas to a new situation is required.

Table 1 Paper I (Draft)

Table 2 Paper-II (Final)

The draft paper consists of three major parts. In the first part students explain each political ideology. Benefiting from the course material that describes various political ideologies, students are expected to uncover the implicit assumptions and describe the basic arguments made by liberalism and social democracy (recognition of assumptions). In the second part of the paper, students apply the political ideologies to the health care issue, positing what the position of each ideology would be in relation to the ongoing health-care debate in the United States (inference). In the last part, by comparing and contrasting these two positions, students need to evaluate the merits of the arguments associated with the ideologies and construct their own arguments (interpretation and evaluation of arguments). Because these first papers are not meant to be research papers, students only rely on the course material that provides basic descriptions of these ideologies without searching for further evidence about the nature of the health-care issue and debate. After the paper is turned in, students receive extensive feedback on their drafts based on the substance and style requirements of the rubric illustrated in table 3.

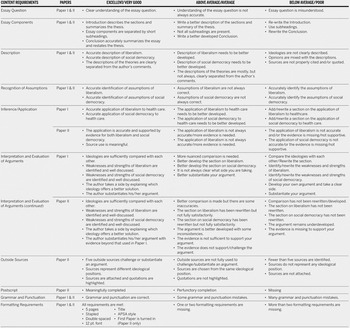

Table 3 Rubric

The second stage (Paper II) of the assignment challenges students to think critically about the conclusions they have already drawn in light of new information (deductions). This goal is addressed through student-conducted research, which adds a number of sources representing various ideological positions on the health care issue. Searching for outside sources not only exposes students to the first steps of conducting research, but also forces them to read a variety of articles from which they then must choose. Students are required to identify and use at least five sources to substantiate or challenge an argument. We also require that all sources are attached to the papers with the quoted sections highlighted so that the instructor or teaching assistant can evaluate the student's use of sources in quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing, and citation.

In addition, most parts of the final paper, as illustrated in column 2 of table 2, remain the same. However, as the students return to their work in Paper II, they reflect on the earlier draft (Paper I), on the instructor's feedback, on the new assignment requirements, and on the new source material. Moreover, students are expected to write better and more detailed interpretations and evaluations than they achieved in the first paper as required by the final paper's question. In other words, the second paper requires revision based on feedback and additional information. This revision requires a rethinking of initial premises, which encourages several distinct critical thinking skills: the evaluation of previous claims in light of new information, the critical examination of assumptions defined in the first draft, inferences drawn on an increasingly complex set of information, and interpretation based on both old information and new information. For the revision, students are also strongly encouraged to use the university's writing center to obtain peer feedback and develop sustainable, self-initiated revision processes. In short, the two-part assignment engages students in an increasingly complex academic conversation that is enriched through the addition of new sources and additional perspectives that must be thoroughly considered and evaluated for the second paper.

To emphasize the importance of each stage of the assignment, both papers carry the same grade value—15% of the final grade. Receiving good feedback on the first paper, however, does not guarantee a good grade on the second paper. Because the second paper requires additional steps and the standards are higher (see the grading rubric at table 3), a student could receive a lower grade on the second paper. For accurate evaluation of the improvement between the two versions, students are required to submit their first papers with the second (final) paper as well as to include copies of the outside sources, as previously mentioned.

The postscript, in which students self-assess their revision and reflect on what they have learned from the entire writing assignment, is one of the most important requirements of the second paper. This exercise is often referred to as metacognition, or the kind of thinking about thinking, or taking a “critical (metacognitive) stance towards the actual process of critical thinking and its representation” that lies at the heart of critical analysis (Moon Reference Moon2008, 126). Students have the opportunity for self-reflection on the progress and the evolution of their ideas. Furthermore, they can articulate their aims, shedding light on their intentions, even when the actual performance may fall somewhat short.

We find that the rubric, illustrated in table 3, helps convey our objectives to students and clarify our expectations. Rubrics, or scoring guides, are helpful for at least three reasons: (1) They make it easier for students to understand the requirements of an assignment; (2) they help students understand the rationale of their grades by specifically seeing the relationship between comments on their papers and the evaluation criteria presented in the rubric; and (3) they help both instructors and teaching assistants/graders maintain standards and consistency.

EVALUATING PROGRESS: SAMPLE PARAGRAPHS AND POSTSCRIPTS

Students demonstrate significant progress between the two papers. In many cases, they realize that their understanding of the concepts has been inadequate. More generally, the second papers present, in general, clearer and more accurate definitions. In revising their first paper (draft), students' arguments become more coherent, substantiated, and developed. Their distinction between the ideologies becomes clearer, and their grammar and punctuation are generally correct. On average, the second papers have a higher average, by about 10 points, although some papers earn lower grades perhaps, in part, because the second papers are graded more strictly. In the first paper, most papers are located somewhere between Average/Above Average (column 2) and Below Average/Poor (column 3). In the second assignment, papers that clearly fall into the Below Average/Poor category are relatively few, while those falling into the Excellent/Very Good Category (Column 1) and the Average/Above Average category are many.

The draft paragraph, that follows, demonstrates one of the most common mistakes made in the first papers—the inaccurate definition of ideologies. Social democracies are often used interchangeably with socialism, and classical liberalism, which is an ideology that “favors a high degree of individual freedom and a weak state in order to ensure the greatest prosperity even if this means tolerating inequality” (O'Neil Reference O'Neil2010, 64), is often confused with the North American version of the term, which “typically implies a stronger state and greater state involvement in economic affairs” (Ibid.) The revision process not only allows students to correct their mistakes, but also to adopt a more global perspective by moving beyond the American case:

Sample Paragraph 1

Draft: Socialism has been a political ideology that has been used by numerous countries throughout history; some have found it very successful while others did not last long under this form of government. The Former Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (U.S.S.R.) declared itself a socialist state in the early 1920s and became a world super power for much of the twentieth century until collapsing in the early 1990s. Currently, China still considers itself a socialist state and has seen a rapid growth in its economy in the past decade.

Final: By regulating and avoiding privatization of these social expenditures, social democratic countries can ensure equality among its citizens. Social democracy has been a political ideology that has been used by numerous countries throughout history and aspects of it can be found in numerous governments in European countries.

Many students also have difficulty incorporating evidence into their arguments. The draft that follows applies the liberal ideology to healthcare without use of outside sources, although the second one, the revised paragraph, incorporates several sources to explain what liberal ideology would offer to discussions of the 2010 health care law. Additionally, comparing the two versions suggests that a revision that incorporates outside sources helps students become more aware and critical of their own biases. This review allows students to see differing frameworks and perspectives that challenge their existing beliefs:

Sample Paragraph 2

Draft: In applying this ideology to the health care issue, liberalism would see the new health care bill as unacceptable and unconstitutional. Universal health care not only restricts the effectiveness of competition in the economic aspect of the health care industry, but also gives the government too much control over people's lives. Individual liberties should not be sacrificed in order to make sure everyone gets equal benefits. A liberal would say that life is inherently unequal because people are inherently different. Some people work harder than others and therefore earn more benefits. Health care should follow the capitalist free market system that liberalism supports. It should be very loosely regulated by the state, but for the most part free, private and competitive.

Final: Liberals have fought the new legislation because they fear that government involvement in health care will “undermine American family values” (Outside Source #1), result in a “detrimental effect on innovation” (Outside Source #2), and create an “'Orwellian' financial cap on the value of human life” (Outside Source #3). Giving the government enough power to control such a massive economic and social system as health care would go completely against liberal values of individual freedom and minimal government. In fact, some say that giving the government power over universal health care is stretching “Commerce Clause powers beyond its current high watermark,” (Outside Source #4). Most of all, liberals fear that “If government can waive a magic wand and lower costs … why stop at health care?” (Outside Source #3) If some individual liberties are relinquished for the common good, then who's to say that the government will not abuse that power further and infringe upon other individual rights? Keeping our current system would drive out excess profits and keep health care “affordable for all policyholders” (Outside Source #3).

In addition to their growth in comprehension that occurs as result of the drafting strategy, students also report that they appreciate writing the postscript because it provides an opportunity for them to reflect on the entire assignment and show awareness of their learning processes. In their postscripts, students specifically report three distinct benefits of the assignment. First, they state that a revision allowed them to have better understanding of the ideologies and the distinctions between them.

Sample Postscript 1: When revising my paper I changed the many mistakes in my definitions of liberalism and social democracy, and corrected the confusion of socialism as being the same as social democracy. I also included outside sources to reinforce my arguments of liberalism and social democracy and their positions on the current health care issue. I have learned many thing(s) about the ideologies of social democracy and liberalism and what positions they would take when confronting the health-care issue.

Sample Postscript 2: The most challenging part of this essay was attempting to keep my explanations concise. Both ideologies are very complex, and it was somewhat difficult not to over-analyze important issues. Through this paper I feel my knowledge of both ideologies has greatly improved, as has my ability to write concise analytical arguments.

Second, students report that their ideas have been challenged as a result of a more careful rethinking of the question, a process that is encouraged by instructor feedback and by the addition of perspectives from outside sources. As a result, students state that they revisited and developed their arguments in the second stage of the assignment:

Sample Postscript 3: The changes made to this paper between the first draft and second draft have improved it greatly. The suggestions made by the TA's were applied, and made the essay more coherent and effective. In the process of revising and adding outside sources it became abundantly clear to me that additional information solidifies the credibility of an argument, the outside sources provided offered a variety of opinions and valid quotes to integrate into the essay…. (I)t was challenging, but I believe this essay effectively demonstrates the importance of integrating outside sources in an argument.

Sample Postscript 4: This paper forced me to reevaluate what I thought I knew about both liberalism and social democracy. Both terms lumped into umbrella terms in meaning; however, the true meanings need to be traced back to their origins for complete understanding. A lot of our political understanding comes in the form of media spin and opinionated editorials that exacerbate misunderstandings of political ideology. This paper helped me better understand the basic tenets of both ideologies to better filter out invalid assumptions when these terms are applied.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, students report that they learn about the implications of abstract theories. They report connecting their learning to considerations of the real world consequences of the varied ideologies

Sample Postscript 5: This essay has helped me to learn how to produce a coherent argument and use sources to produce a strong argument. It also has helped me to better understand the liberal and social democratic ideologies by trying to apply what each ideology would think with regards to a very real issue, that being the health insurance law. Finally, the essay made me connect knowledge gained through this class to the “real world.”

Sample Postscript 6: Writing a five-page paper on these ideologies from just knowledge of the book made the fundamentals clear and examined to the full extent. Having learned these ideologies and having that clear understanding made it possible to connect what I learned from the book to outside sources. Now I not only have a clear understanding of the ideologies but can connect them to outside sources because of what I have learned. Even better yet I will now be able to look at a political system in the future and declare it as liberalism or the social democracy I have knowledge of.

CONCLUSION

Although critical thinking skills are essential for members of a “learning society,” a society that is open to progress (Barnett Reference Barnett1997, 159), critical thinking nevertheless remains an underaddressed objective of higher education. This shortcoming remains despite Barr and Tagg's (Reference Barr and Tagg1995) now-famous call for learning communities, in which students demonstrate discernable learning outcomes directly connected to curricular goals to replace teaching communities (the traditional model of higher education in which students are passive recipients of information). Faced with the significant challenge of the development of more critical and effective thinkers among our college graduates, we are undoubtedly past due in generating meaningful, if never wholly adequate, solutions. Although we do not wish to suggest that critical thinking skills can be summarily addressed through a pair of linked writing assignments, we do contend that the writing assignment we posit here offers distinct advantages over most traditional writing assignments. The linked writing assignment takes into account the learning needs of students; it builds incentive for students to attend to instructor feedback; and it provides opportunity for correction and refinement of ideas and their presentation. As such, we believe that this assignment addresses many of the challenges we face not only with student writing, but with student thinking and learning. We encourage other instructors in political science to consider the systematic use of writing, and in particular feedback loops and staged, scaffolded writing assignments, to advance the development of better citizen-thinkers and engaged members of the introductory political science course.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An earlier version of this article was presented at the The Institute for Teaching and Learning (TILT) Summer Conference on Learning, Teaching, and Critical Thinking, May 19, 2010, Fort Collins, CO. We would like to thank the teaching assistants Dawn King and George Stetson for proposing the initial idea and Mathew Luizza for helping us develop it. Special thanks to Jamie Barringer and Amy Lewis for their help.