This essay explores the causal relations between the greatest economic and social transformations of the early colonial period in West Africa: the “cash-crop revolution”, “the slow death of slavery”, and debt bondage.Footnote 1 The development of export agriculture, in place of the export of slaves, defined the “modern” pattern of the region’s economies: a comparative advantage in (and dependence on) the produce of the soil, and unequal but wide ownership of the means of production, in contrast to the domination of the slave trade by rulers and large merchants. The ending of slave trading, slavery, and human pawning overturned the major institutions for the mobilization of labour from beyond the family (though all intersected with family relations). Both processes have inspired substantial historiographies; but the connections between them have been relatively little examined. However, many pertinent observations and ideas can be found in these literatures, not least in work produced during the last decade. The aim of this essay is to develop a synthesis, to provoke debate, and to suggest lines of further research. I focus on the French and British colonies, which in 1914 comprised about 94 per cent of the region’s population and more of its area.Footnote 2

The discussion begins with an introduction to the historical context and historiographical issues. I then examine the economic considerations in the formation of colonial governments’ policies towards slave trading and slavery, before assessing the contributions of slave labour to the growth of cash-crop production. The analysis then moves to the various mechanisms by which the expansion of export agriculture shaped the ways in which slavery declined: especially the destinies of former slaves and former masters. I consider the effects of emancipation on the economies, short- and long-term. Finally, I briefly explore the implications of the interaction of cash-cropping and the ending of slavery for inequality and social hierarchy: the proliferation of peasant households, and the persistence or otherwise of the old elites.

History

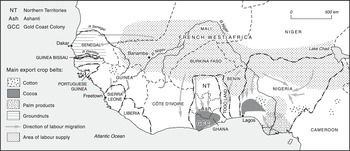

The emergence of export agriculture began during the protracted abolition of the Atlantic slave trade, decades before the European Scramble for Africa (the latter happened essentially between 1879 and 1903). The major products were groundnuts (peanuts) and palm oil. The former were produced for export on the coasts and estuaries of the western Sudan (mainly from Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea Bissau)Footnote 3; the latter from the forests of the Guinea coast (especially from Sierra Leone to south-eastern Nigeria and into Cameroon).Footnote 4 The 1880s to the 1900s saw the global frenzy for wild rubber, which West Africans helped to supply, from what became French Guinea east to what is now Ghana (Figure 1 overleaf)

Figure 1 West Africa in 1914. The political boundaries shown are as of 1914; the bolder lines distinguish territories belonging to different colonizers, while the less bold lines distinguish different colonies of the same power. The countries have been given their postcolonial names except for the German colony of Togoland, whose territory today comprises the republic of Togo and part of Ghana. Guinea-Bissau was Portuguese. The Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Nigeria were British colonies. The others were French.

.

Under colonial rule the agricultural-export economies spread from the coast to incorporate the whole of West Africa. The zones of export production were extended inland and new ones were opened, spearheaded by newly built railways. The major producing areas were the forest zones, for cocoa and palm oil, and those parts of the savanna that were both suited for groundnut growing and had relatively low transport costs: primarily the Senegambian groundnut basin, and the area of northern Nigeria in range of the railway, which reached Kano in 1912. South-west Nigeria and the Gold Coast shifted from palm oil to the exotic tree crop, cocoa. The adoption of cocoa, and also of groundnuts as an export, was largely at the initiative of indigenous producers and traders. In the northern Nigerian case it confounded British hopes that the colony might become a major supplier of raw cotton to Lancashire.

These were the more prosperous parts of the region (the growth of their output is summarized in Table 1 below). The rest of West Africa mainly comprised inland savannas, where a short planting season and particularly thin soils combined with high transport costs. These areas also became integral to cash-crop production, but in less lucrative ways. French Soudan (Mali) and northern Côte d’Ivoire, for example, became growers of cotton (in some cases under coercive pressure, direct or indirect, to do so) and/or, by the 1920s, suppliers of migrant wage labour to the main cash-crop districts. In various parts of the region local trade in food crops expanded to serve the centres of export-crop production and marketing.Footnote 5

Table 1 Main agricultural exports from main producing colonies, 1890–1914 (metric tons)

*For comparison, in 1900 Lagos accounted for 56 per cent of the total (see Berry, cited below).

Note: – means no figure available. In Nigeria in this period exports of cocoa beans, palm oil (and palm kernels) and groundnuts came from the south-west, south-east and (at least after 1912) north respectively.

Sources: Sara S. Berry, Cocoa, Custom and Socio-Economic Change in Rural Western Nigeria (Oxford, 1975), p. 221; Gerald K. Helleiner, Peasant Agriculture, Government, and Economic Growth in Nigeria (Homewood, IL, 1966), Table IVA8; Polly Hill, The Migrant Cocoa-Farmers of Southern Ghana (Cambridge, 1963, repr. Hamburg, 1997), p. 177; G.B. Kay with Stephen Hymer, The Political Economy of Colonialism in Ghana (Cambridge, 1972), p. 336; Susan M. Martin, Palm Oil and Protest: An Economic History of the Ngwa Region, South-Eastern Nigeria, 1800–1980 (Cambridge, 1988), p. 148; James F. Searing, “God Alone is King”: Islam and Emancipation in Senegal: The Wolof Kingdoms of Kajoor and Bawol, 1859–1914 (Portsmouth, NH, 2002), p.199; Kenneth Swindell and Alieu Jeng, Migrants, Credit and Climate: the Gambian Groundnut Trade, 1834–1934 (Leiden, 2006), pp. 23, 101, 149.

Meanwhile, the sale and holding of slaves, along with human pawning, had declined; unevenly over time and space, often very slowly, but in most areas decisively by 1930. It is important to emphasize both the seismic scale of the overall change, and the very gradual approach taken by the colonial powers. At the time of the colonial conquests, slaves comprised a large minority of the populations of most societies in the region, and a majority in certain desert-edge populations (typically sedentary farmers, under itinerant Tuareg masters). The most systematic data for the incidence of slavery in West Africa come from careful examination, in context, of admittedly very imperfect French surveys carried out in 1894 and 1904 (by the latter date, many slaves had left on their own initiative). Martin Klein estimates that, for French West Africa as a whole, over 30 per cent of the population were slaves at the turn of the century.Footnote 6 For the largest pre-colonial state in the region, the Sokoto Caliphate (centred in what is now north-west and north-central Nigeria), Paul Lovejoy and Jan Hogendorn put the slave population at the time of conquest (1897–1903, by Britain, France, and Germany) as “between a quarter and a half of the population of the Caliphate, which certainly numbered many millions and perhaps as many as 10 million”.Footnote 7

Britain and France had already proclaimed the abolition of slave trading and slavery in their colonies long before they became rulers of most of West Africa. Before the Scramble, Britain colonized the Gold Coast proper (the southern quarter of what is now Ghana), and proclaimed the abolition of slave trading, slavery, and debt bondage.Footnote 8 But during and following the Scramble itself, such urgency was usually absent; though European officials and politicians made this as little obvious as possible to voters and humanitarian lobbies back home.Footnote 9 Admittedly, in some cases the slave trade was promptly banned and enforcement attempted, as in Ashanti and northern Ghana from 1896.Footnote 10 Moreover, the conquerors sometimes used proclamations of slave emancipation to undermine the resistance of African rulers, as the French did in various places and as the British did in the Benin kingdom in southern Nigeria in 1897.Footnote 11 In the latter case, however, as Sir Frederick Lugard, later the first governor-general of Nigeria, was to comment, it proved “necessary […] to legalise the institution under some other name, as was in effect done by the House Rule Proclamation” of 1901, which forbade servants from leaving their masters.Footnote 12

During the conquest the French army needed to reward its soldiers, most of whom were African, and for whom the most valuable booty at the time was slaves. Colonial commanders, and the civilian administrators that followed them, were under-staffed and very much needed the cooperation of allies and of local chiefs in general. The latter relied on slavery for many of their own staff. Klein has documented persistent, though not consistent, acquiescence in the continuation of slave trading, let alone slavery, by French officials in the years of conquest and early administration.Footnote 13 Near the Nigeria border in German (and briefly French) Cameroon, the emir of Madagali enslaved over 2,000 people that he captured in raids on “pagan” mountain peoples in his neighbourhood, between 1912 and 1920.Footnote 14 By 1912, however, in most parts of West Africa regular slave raiding and trading had been suppressed, and cases were more likely to concern clandestine kidnapping of children. Meanwhile, in most of the region the measures taken against slavery itself had been largely confined to abolishing the legal status of slaves: as happened in Nigeria in 1900–1903 and in French West Africa most clearly in 1905. This meant that colonial administrators and courts would not return runaways. Without the backing of the coercive power of the state, slavery as a widespread social institution was doomed to wither.

That process was accelerated by the actions of slaves themselves, variously taking advantage of the military defeat of their masters or believing that the colonial state would ensure that they would not be returned to their masters, or anticipating formal emancipation. Some of the colonial conquests triggered mass departures of slaves, notably in southern Yorubaland (in south-western Nigeria) during 1892–1895.Footnote 15 The most dramatic exodus, involving hundreds of thousands of slaves, was centred on Banamba and spread to neighbouring areas of Malinamba. The result was that slavery as a system fell apart between 1905 and 1910. The scale of the 1905–1906 mass departures from Bambara forced the hands of colonial administrators who had initially hoped that “servants” would stay with their masters.Footnote 16 Other slaves stayed put and often negotiated or were given improved conditions. Klein estimates that in French West Africa as a whole “probably over a million” slaves left their masters between 1905 and 1913.Footnote 17

Yet in certain colonies, slavery persisted even in law. In northern Nigeria an estimated 200,000 women were legally bound under a form of slavery disguised as concubinage until 1934. If the law in northern Nigeria contained a big loophole, in Sierra Leone the loophole was coextensive with the law. As late as 1927 an ordinance was passed allowing masters to use “reasonable force” to recapture runaways. The consequent political uproar in Britain and in the International Labour Office led to the legal status (only) of slavery being abolished the following year.Footnote 18 In Mauritania, slavery has been even more persistent, but over most of the region slave status as a source of labour was at most marginal by 1930.

Historiography

There are substantial literatures on both these transformations. The origins of the wage labour market, and even more of export agriculture, were the focus of much of the first generation of continuous professional research into West African economic history, from the later 1950s to the end of the 1970s. Much of this writing showed no awareness that slavery had even existed in the nineteenth century. This seems odd because almost any acquaintance with books published on West Africa before or during the early twentieth century would have corrected that impression.

One can only speculate that the economists who pioneered the literature projected backwards from the composition of the West African labour forces of their own day, subtracted hired labour, and were left only with free family labour. Thus the assumption was that the labour came overwhelmingly from farm-owners themselves and (“free”) family members until the family labour forces were supplemented, as the colonial period went on, by migrant wage labourers.Footnote 19 The latter moved seasonally between the zones of cash-crop cultivation and their own homes, which were in areas where soil quality and/or transport costs were such as to render export production on their own account unprofitable. Elliott Berg’s pioneering study of “The development of a labour force in Sub-Saharan Africa” (1965) located the “recruitment problem” in the period c.1880–c.1930. The author proceeded to define this problem as “the transfer of labour resources out of the villages of the subsistence sector into paid employment”.Footnote 20 Slavery within Africa is not specifically mentioned in the article, even though it gave attention to the use of forced labour by colonial governments.Footnote 21

That the original labour force was overwhelmingly family-based was also an undocumented premiss of the then dominant economic interpretation of cash-crop expansion. This was the “vent-for-surplus” model, which attributed the economic growth to the application to agriculture of previously idle labour and land.Footnote 22 The notion that the labour was mobilized from a reserve of leisure would have been hard to reconcile with the proposition that labour was scarce enough for there to be any sort of market for labour, whether for labourers or for their services. That contradiction was not pointed out in those of the early critiques of vent-for-surplus that mentioned slavery.Footnote 23 Probably this was because the scholarly literature on nineteenth-century pre-colonial slavery and its eventual demise was very scattered until the mid-1970s, when it took off sharply.

Partly because it would have seemed inappropriate at the time, slavery within Africa had not figured on the research agenda in the era of decolonization, which was the period when African history became the subject of regular professional study. This changed in the 1970s, particularly at the initiative of French Marxist scholars seeking to identify the characteristic “mode(s) of production” of pre-colonial Africa.Footnote 24 The flow of research on slavery within Africa, and on its eventual decline, has barely faltered since. Among other findings, this work has shown that slavery was much more widespread in the pre-colonial nineteenth century than was previously supposed, and also that its incidence was not stable. Rather, the use of slaves within West Africa became considerably more common as the Atlantic slave trade declined, facilitated by the downward pressure on the price of slaves in West Africa as shipments fell.Footnote 25 Slave use rose further in the later nineteenth century when state-builders, above all Almami Samori Ture, took and sold captives on a massive scale to finance purchases of horses and guns.Footnote 26 Thus the twentieth-century demise of slavery reversed a trend as much as it abolished a status quo.

Also, the monographic evidence is very much that the expansion of slave-holding responded to the demand for additional labour by rulers, merchants, and heads of households engaged in commodity production.Footnote 27 The expansion of the latter was not limited to palm produce and groundnuts for the Atlantic trade. It also included a major growth of market activity in the economies of the central Sudan, centred on the Sokoto Caliphate, and in their forest trading partners. The inhabitants of slave villages or plantations grew some of the grain and most of the raw materials for the handicraft cotton textile industry of Kano and other towns, the products of which were sold almost throughout West Africa.Footnote 28 Despite this economic angle, the focus of the growing historiography of abolition has been elsewhere: on the interaction of colonial policy and slave agency (through runaways, revolts, and negotiations with masters) in the ending of slavery.Footnote 29

Yet the idea that there were causal relations between the cash-crop revolution and the ending of slavery was not new – just neglected. As early as 1926, while the historical transformations were themselves still incomplete, Alan McPhee’s contemporary economic history of British West Africa claimed for the Gold Coast Colony (the part of what is now Ghana south of Ashanti) that the abolition of slave dealing and the legal status of slavery there in 1874 had “negligible” effect until changes including “the development of the cocoa industry” dealt it a “staggering blow” by, he implied, creating a “free labour market” offering “alternative employment” to former slaves.Footnote 30 In 1973, for West Africa as a whole, A.G. Hopkins argued that export agriculture helped freed slaves establish themselves as farmers and migrant labourers. This helped make possible a “transition from slave to free labour […] without widespread economic and social dislocation”.Footnote 31 These studies, in identifying and in McPhee’s case highlighting a causal relationship from the growth of export agriculture to the accelerated ending of slavery, raise an issue which, as will be seen below, has now attracted more attention.

A causal relationship in the opposite direction was hinted at but not elaborated in three works by Marxist scholars from the 1960s to early 1980s. In his history of French colonial rule in Africa, Jean Suret-Canale devoted a section to “The Decline of Slavery”. He asserted that African “domestic slavery […] presented a serious obstacle to colonial exploitation”. This was on the grounds that slavery reduced the labour productivity of both the enslaved person and the potentially indolent master.Footnote 32 But most of the section described the compromises that the French felt obliged to make in implementing their commitment to abolition; and if the eventual result was higher productivity, the book does not confirm it.Footnote 33

In a later study of Nigeria, Sheila Smith set out to examine the role of the colonial state in the transformation of Nigeria into a primary produce exporter. She described “the abolition of slavery” as one of “the active interventions of the state [that] were crucial in generating and maintaining the conditions for the production of cash crops for export”.Footnote 34 But she did not say why abolition was one of these conditions, and her section on abolition was devoted to the difficulties faced and compromises made by the British during the process. These included economic disruption that would have resulted had abolition been sudden – which it was not.Footnote 35 Smith’s otherwise incisive article nowhere specified how abolition actually constituted a condition for the production of agricultural exports. Finally, Mansur Muhtar, for northern Nigeria, offered such a proposition: that by transforming “unfree labour into a pool of free men”, abolition could raise productivity.Footnote 36 Whether there is evidence for this remained – and still remains – to be seen.

Recent monographic research has begun to put the stories of export agriculture and the decline of slavery together, and to examine the evidence on possible causal interconnections. In 1983–1984 B.A. Agiri described the succession of slave, pawn, and wage labour in agriculture during the growth of cocoa-farming in southern Yorubaland.Footnote 37 In 1993 Lovejoy and Hogendorn, in a major study of the end of slavery in northern Nigeria, though primarily concerned with the legal and social status of slaves and former slaves, devoted a chapter to “The colonial economy and slavery”. They concluded “The increased opportunities for slaves to earn cash income that were available from 1912 [after the opening of the railway from Kano to the coast permitted groundnut exports to take off] were instrumental in easing the transition from slavery to freedom”, though “most” former slaves “did not escape poverty, and many of their descendants are poor today”.Footnote 38 More assertively, in 2002 James Searing argued that “the dynamic growth of the peanut economy explains the rapid decline of slavery in the peanut basin” of Senegal. Specifically, his study of two former Wolof kingdoms in Senegal emphasizes the crucial role of cash-cropping in providing economic alternatives for slaves looking to leave their masters.Footnote 39 In 2005 I examined in some detail the relations between the adoption of cocoa-farming and the decline of slavery and debt bondage in the former kingdom of Asante, in what is now Ghana.Footnote 40 The sections that follow explore the issues across colonial West Africa as a whole.

Abolition: economic considerations in colonial policy

That the colonial administrations would legislate against the trading and holding of slaves was a political given. The only question was how much scope for compromise and ambiguity – ultimately, how much time for delay – they were to be allowed by their political masters in the imperial capitals. The latter had to respond to the intermittent nagging of missionaries, anti-slavery organizations and awkward members of parliament. Indeed, they were answerable ultimately to voters who had been told that the abolition of slavery was one of the aims of Empire, and who probably thought that it had already been achieved. The issue to be discussed here is whether economic considerations on the spot encouraged militant action or, rather, compromise and delay.

An important recent book by Kenneth Swindell and Alieu Jeng claims that “although many West African [colonial] administrators were fearful of the flood of slaves into the towns, and the creation of lawless vagrants, they were attracted to the idea that abolition was essential for the creation of a wage labour force and expanded production”.Footnote 41 While the fears are readily documented, it is hard to find evidence of serving officials in West Africa, in advance of the fact, wanting to see slave labour replaced by wage labour. Like the three Marxist scholars mentioned earlier, Swindell and Jeng provide no such evidence. In the case of William Merlaud Ponty, Governor of Haut-Sénégal-Niger (including what is now Mali) and later Governor-General of French West Africa, Klein describes his welcome for the free labour market as “retrospective”; following the disintegration of slavery in the French Soudan because of the exodus of 1905–1908.Footnote 42

Regarding slave trading, rather than slavery, there was a pragmatic economic case for ending it swiftly, because it basically pre-supposed raiding or kidnapping. The violence involved, though largely restricted to areas outside the home territories of powerful states such as the kingdom of Asante and the Sokoto Caliphate, was inconsistent with the interests of trade and the generation of taxable income. The vast areas depopulated by Samori represented agricultural and fiscal waste as well as human suffering. Even so, we have seen that initially French officials were not always keen to act against the trade, because their allies among the African rulers drew income and personnel from it.

On slavery itself, colonial officials appear to have been unimpressed by Adam Smith’s famous contention of 1776 that free labour is more efficient than slave labour. Indeed, over the century and more that followed, even the leaders of the abolitionist movement were never collectively confident about it.Footnote 43 By the turn of the twentieth century, for European commentators and administrators, the experience of the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean had compounded this caution.Footnote 44 There, sugar exports fell while the former slaves’ living standards rose.Footnote 45 The freed slaves had preferred to work for themselves rather than for their former masters; in this period, such work tended to counted for little or nothing in the official mind.

This perception was expressed by Mr Denton, Acting Governor of Lagos, in 1898: “I much fear that as they [the slaves] can find the means of subsistence ready to hand without work they will cease to do anything in the way of cultivating the land as soon as the restrictions of domestic slavery are removed”.Footnote 46 “Suppress the slaves” [sic], wrote a French local administrator in Senegal in 1904, “and the fields will remain uncultivated and the colony will be ruined”.Footnote 47 Georges Poulet, author of a major report on the issue of emancipation for the French government, in 1905, believed that a radical policy of emancipation in French West Africa could cost “half a billion francs” in lost revenue.Footnote 48 In Sierra Leone, the Creole elite of Freetown – ironically, themselves descended from freed slaves – maintained a long-running argument (notably through their press) against abolition on the grounds that it would damage the economy of the interior of the colony, reducing trade and increasing vagrancy.Footnote 49 In Nigeria in 1904 the British administrator (“Resident”) in Ilorin, in the north of Yorubaland, feared that if the slaves were freed the

[…] farmers could not pay for sufficient hired labour to keep the Province in its present flourishing condition and the markets would suffer severely. Again, if these slaves […] were forced to be free, the old master would not be likely to feed and house them and they would have to shift for themselves. There would then be a great danger of them turning into highway robbers […].Footnote 50

As this illustrates, Klein’s comment that the colonial state saw freed slaves “as vagabonds and potential criminals who sought freedom not to work but to avoid work” is applicable, as a generalization, to British as well as French West Africa.Footnote 51 Productivity and public order were thus jointly threatened.

A more qualified view was expressed in a contemporary (1907) study of the labour problem in French African colonies. Robert Cuvillier-Fleury put a more charitable gloss on the “refusal” of freed blacks to work, which he considered the experience to date. He attributed it to distaste for manual work resulting from the experience of slavery.Footnote 52 Understandable as such distaste was, the implication was that abolition would reduce, not raise, productivity. Cuvillier-Fleury qualified his argument by suggesting that “agricultural crisis”, where slavery had already been abolished (as in the Caribbean), might have been avoided had the slaves been put through a transitional state of semi-constraint to allow them to adapt to eventual freedom.Footnote 53 He thought that in Africa the abolition of the slave trade had already led to an amelioration of slavery, converting it to an esclavage de case.Footnote 54 The implication is that when slaves in Africa were eventually freed, their contempt for work would also have been ameliorated. While insisting that in Africa, too, “[t]he free man is generally less lazy than the slave”, he considered that freed domestic slaves would be capable of responding to economic incentives.Footnote 55 Thus, presumably, the end of slavery in Africa would not produce agricultural crisis after all. While less pessimistic than the likes of Denton, this is hardly in the optimistic tradition of Adam Smith.

Productivity was not the only consideration for those charged with making and implementing colonial policy. Disruption and distribution mattered too. As things stood at the beginning of colonial rule, slaves were a large and integral part of the workforce. If they left their masters there would be a shock to output and revenue, even if they immediately set about finding work, whether for themselves or for wages.

In this context, it should be noted that the pre-colonial slave trade functioned as a labour market, moving slaves to the areas where the prospective masters could pay most for them, because they could obtain relatively high market returns from slave labour. This meant that the major slave-importing societies were those most engaged in the production of commodities, whether for markets within Africa or for overseas. A major example was the kingdom of Asante, where kola was produced for sale to Hausa traders from the Sokoto Caliphate to the north-east; and where gold and (from the 1880s) rubber was produced and sold on the Gold Coast to the south. Most of Asante’s new slaves were imported from the north, very often sold by those same Hausa traders, having been seized in the northern savannas, where opportunities for commodity production were less lucrative.Footnote 56 Another example was the Gambia, growing groundnuts for sale to European ships, and again importing slaves from its hinterland.

The mass return of freed slaves would benefit the areas to which they returned. But it would reduce productive capacity, at least temporarily, in the more market-oriented economies from which they were freed (or freed themselves). This shortfall would last at least until a free labour market could tempt them back for hired labour, or attract replacements. In 1893 the commissioner of the North Bank district of the Gambia wrote that

To proclaim the freedom of all slaves […] would have the effect of paralysing all trade and cultivation, as all the hard work is done by the slaves; their masters, being either too old or unaccustomed to hard work to take to it all at once. The slaves would all return to their country, and the population be considerably reduced.Footnote 57

Both British and French officials were especially concerned about the implications of abolition for the chiefs, on whom they depended for day-to-day control and government of the mass of the population. Officials were keenly aware that the chiefs depended on slaves for both administrative and productive labour. Chiefs themselves were quick to remind the Europeans of this, in protests against abolitionist proposals. The most powerful Futa chief, Abdul Bokar Kan, wrote to the French governor of Senegal in 1889: “it is impossible for us to live without slaves because they work for us. Slaves for us are as money and merchandise are among you”.Footnote 58 In response to the mass exodus of slaves from the Banamba area in what is now Mali in 1905, Maraka chiefs threatened a tax strike if the French did not use force to stop it. The administration started to oblige, forcibly returning a group 200 slaves to the town of Kita, but ultimately could not hold the line.Footnote 59 In Sierra Leone, the chiefs who led the Hut Tax Revolt of 1898 “listed government efforts to dismantle domestic slavery as one of the most important of their reasons for taking up arms”.Footnote 60 Thus, a quick abolition would badly disrupt the income and probably executive capacity of chiefs, and their might in the eyes of their subjects. Longer-term, too, the viability of colonial rule through the chiefs (whether it was official, as in the British case, or de facto, as often in the French) could be compromised by a redistribution of the control of labour, and therefore of access to income, from the rich and powerful to their former slaves.

Finally, the reason why slavery paid in nineteenth-century pre-colonial West Africa was that, with land abundant (physically and institutionally) and labour scarce, free wage rates would have been relatively high.Footnote 61 Indeed, I have argued elsewhere for the case of the Asante kingdom that it would have been impossible to find a wage rate that would have been in the interests of both an employer to offer and a worker to accept. Thus, the economic alternative to slavery and slave trading would have been the absence of any market for labour at all, beyond casual employment.Footnote 62 This proposition was put at the time, in different words, in a petition to the governor of the Gold Coast from an Asante chief and elders in 1906: they said they depended on the labour of slaves and the descendants of slaves “as we have no money like white men to hire men to do necessaries for us”.Footnote 63 It may be added that the economic logic for labour coercion in the context of land abundance was being elaborated at the time by the Dutch economist, H.J. Nieboer (writing in English); and had been anticipated in part by Edward Gibbon Wakefield several decades before.Footnote 64 I am not aware of any evidence that colonial officials read or even knew of either Nieboer or Wakefield. But they had to deal with the kind of economic conditions that Nieboer, in particular, had described.

Where there was a substantial gap between colonial conquest and the abolition of, at least, the legal status of slavery, one might suppose that the eventual decision to act against slavery (whether its legal status, or compulsory emancipation) was a response to changed economic conditions: a shift to land scarcity and labour abundance. That would fit the theory of induced institutional innovation, the standard economic explanation of how institutions such as property rights in land and labour change: that they respond to shifts in the relative scarcity of factors of production.Footnote 65 An erosion of the abundance of land in relation to labour would be expected from the growth of export agriculture. But in West Africa, delayed as abolitionist measures often were, they were introduced before land–labour ratios had altered much. Elsewhere, I have shown this quantitatively for the case of Asante, where the British occupation began in 1896, cocoa was planted rapidly from 1901, and slavery was banned in 1908.Footnote 66 In sum, the effect of economic considerations on colonial policy was, if anything, to weaken rather than strengthen the case for prompt action against slavery.

Slave labour in the cash-crop revolution

In view of the pessimistic expectations of chiefs and European officials about the likely economic impact of an early abolition of slavery, it is not surprising to find that slaves made major contributions to the growth of export agriculture in the early years of colonial rule. We have already seen that they provided much of the labour during the expansion of commodity production during the pre-colonial decades of the nineteenth century, both for markets within the region and for the maritime trade. However, these contributions declined under colonial rule, more or less rapidly, with freed slaves providing increasing inputs.

We should begin by making two qualifications about the significance of slave labour for commodity production in the decades between the beginning of the end of the Atlantic slave trade and the Scramble. Both are relevant to what was to happen after colonization.

First, coercion was not always the only way of mobilizing labour from outside one’s household for farming. An alternative existed where the land concerned was exceptionally valuable, in the specific crops that it could support and in its proximity to market. In the Gambia from the 1830s, and later also in Senegal, groundnut production attracted voluntary immigration from the interior of western Sudan, the migrants effectively renting land, and sharing the groundnut crop with the landlord.Footnote 67 In noting the importance of this consensual labour, however, we need to remember also that of slavery. According to Swindell and Jeng, in 1894 “slaves outnumbered freemen by two to one” in the north bank district of The Gambia, “the historic core of the groundnut trade”.Footnote 68

Second, in south-eastern Nigeria slave labour made a bigger indirect than direct contribution to the growth of commodity production in the decades before the British conquest. The area of export production itself – the oil-palm belt – benefited from an unusually high density of population, enabling it to produce oil and kernels for sale without extensive use of slaves. But this was made possible by importing foodstuffs from its northern hinterland, which had a much lower population density, and where production relied heavily on the use of slaves.Footnote 69 Also just outside the oil-palm belt, the women weavers of the town of Akwete developed a new kind of luxury cloth to sell to the prosperous palm-oil producers. As their business expanded, weaving became a year-round, full-time rather than seasonal and part-time occupation. The weavers found time to specialize by delegating other tasks to slaves purchased with their profits.Footnote 70

Colonization was soon followed by further expansion of agriculture for overseas markets, as we have seen, including the adoption (where possible) of cocoa-farming. Colonial governments initially increased the use of one form of labour coercion: forced labour for the state, whether for the government or for (or via) the chiefs. Also, compulsory cultivation was one of the methods used by the French to promote cotton production, especially in the mid-1920s, though it always yielded very limited results.Footnote 71 Pressure by colonial authorities on farm owners was apparently much less effective than had often been true of the pressure applied by farm owners to slaves and pawns, as part of their workforces. The requisitioning of labour by the colonial state was particularly direct and prevalent in the French colonies, until its abolition with effect from 1946. Besides public works, such labour was also used to help French planters, unsuccessfully seeking to make Côte d’Ivoire into a settler colony. All over colonial West Africa, until after World War II, including in the British colonies, labour was also requisitioned through chiefs or village headmen to build roads, in the name of communal labour. This tended to diminish after the colonial powers reluctantly signed the international Forced Labour Convention of 1930.Footnote 72

The greater importance of forced labour in French than British colonies was partly a response to their relatively unfavourable environment: the French monopolized the Sahel, had most of the more arid savanna, and had the territories most distant from the sea. What is striking about colonial coercion in West African agriculture is how little it contributed to the overall growth of cash-crop output from the region. In the most commercially successful of the French colonies, Senegal, the growth of groundnut output dwarfed that which could be accounted for by administrative pressure or tax demands.Footnote 73 More so in the British case, the major commercial successes were southern Ghana (including Ashanti, i.e. colonial Ashanti) and southern Nigeria, which were distinct in having no direct taxation during their cash-crop take-offs.

Where the colonial period saw expanded production of an established export crop, as with groundnuts in Senegambia and palm produce in south-eastern Nigeria, slaves continued to contribute to the labour force, directly and/or indirectly as the case was. In the early 1890s, in areas including Asante and the Baule region of Côte d’Ivoire, as well as the western Sudan, many masters acquired additional slaves; encouraged by low slave prices following from the abundance of captives offered on the market in the 1890s, as a result of the enlarged scale of enslavement by the forces of Samori and others just before and during the early stages of the European conquests.Footnote 74 The use of slave labour was curtailed, sooner or later, by slaves running away, often without waiting for the formal abolition of at least the legal status of slavery. Alternatively, slaves remained in place; but generally did less or no work for their former masters.

In the late nineteenth century West Africans were active participants in the search, across the three tropical continents, to supply the new international market for rubber. In contrast to Leopold’s Congo, in West Africa rubber tapping was, throughout the boom, a field of indigenous enterprise. In the 1880s–1890s it was a fairly wild frontier, in the dense forests straddling the Gold Coast Colony, Ashanti, and Côte d’Ivoire. Slaves figured both as a source of labour and as the object of reinvestment of profits.Footnote 75 By 1910, the boom was over; except and until American companies established themselves in Liberia in the late 1920s, rubber was not profitable as a plantation crop in West Africa, apparently because the labour costs were too high.

African coercion was, at most, inconspicuous in the take-off of production of an exotic crop, cocoa beans, in the Akim Abuakwa district of the Gold Coast Colony, in the 1890s and 1900s, because of the precocious abolition of the legal status of slavery and debt bondage in the colony. Rather, a Gambian precedent was followed, in that farmers from neighbouring districts, short of suitable uncultivated land, voluntarily immigrated to exploit the Akim forest. In this case, however, the farmers drew on a combination of credit and their savings from earlier market activities to buy, rather than rent, the land from the local chiefs.Footnote 76 The Gold Coast Colony case is a famous story of free migrant enterprise. But the story needs qualification.

Raymond Dumett and Marion Johnson reported a “common trend” in the 1880s and 1890s for slaves to be replaced by pawns. The act of pawning had been banned along with slave dealing, but the law was enforced far less vigorously against the former than the latter. They quote a Basle missionary writing in 1895 that “thousands of boys and girls” were now living in pawnage in the Akwapim district, where slavery had “changed into the holding of pawns.” Dumett and Johnson suggested a supply-side link between the spread of cocoa cultivation and the growth of pawning, in that the former led to much litigation over land, leaving families in debt.Footnote 77 Though they did not explicitly link pawns with cocoa labour, it is logical to take the further step of positing that pawning contributed to the early cocoa-farm labour force in the eastern province of the Gold Coast. For they did note that, in general, “heads of farming families” were among those who turned to pawning as a substitute for slavery in the colony.Footnote 78 Moreover, Akwapim was the nursery of Ghanaian cocoa-farming, and Akwapims were very prominent among the migrant farmers who then spread it into the under-used lands of Akim Abuakwa.Footnote 79

Pawning, but also slavery and the chiefs’ right to summon their subjects to make farms for the chieftaincy, provided the extra-familial labour in what became the northern part of the Ghanaian cocoa belt. This was the forest heartland of the former Asante kingdom, where cocoa planting spread rapidly – largely at indigenous initiative – after the defeat of the anti-colonial uprising of 1900. A high proportion of the earliest cocoa farms in Asante were made by chiefs calling upon their subjects’ labour. On the early cocoa farms in general, first-generation slaves (many of them bought from Samori’s forces just a few years before) and pawns did much of the farm work.Footnote 80 Indeed, slavery contributed to family labour, where the children of (almost invariably) slave mothers and free fathers were incorporated into households via cadet lineages. The anthropologist Meyer Fortes made the following note on an interview he conducted in Asokore, in Asante, in 1945.

Wealthy cocoa farmers. (They are not very willing to talk about other people[’]s wealth. I asked if they knew anyone who had become wealthy only from cocoa farming.) At Nyamfa there was a man Kwame Dampa, who had very big cocoa farms wh[ich] he made in the early days. He had “[e]fie nnipa” (descendants of slaves) to work his farms and so got very rich. But if you do not have many sons or money to employ labour you can’t make big cocoa farms.Footnote 81

In the other major cocoa economy of early twentieth-century West Africa, south-western Nigeria, Sara Berry found that “several” of her “informants mentioned slaves as a source of labour on their families’ early cocoa farms”.Footnote 82 Agiri reported other cases, such as “the Oyede family in Ota” who, as of 1902, “employed slave labour to cultivate over twenty acres of cocoa, coffee and gbanja kola”.Footnote 83 In his research on the former Ijesha kingdom, John Peel found that, despite the flight of slaves following the colonial conquest, former warriors or their heirs “still were often able to command the loyalty of ‘slaves’: men who for whatever reason preferred to stay in Ilesha and who needed their former master as a patron”. Thus, “Ajayi Obe was able, when he planted cocoa after 1911, to call on the labour of a handful of former slaves of his father”. Later he gave them plots of their own but they “continued to give part of their time, usually the whole morning […] to their ‘master’, from whom they […] in the end received cocoa seedlings”.Footnote 84

Meanwhile, as Adeniyi Oroge showed, many of the wealthier Yoruba farmers had responded to the earlier (and continuing) slave departures by making use of iwofa, the Yoruba version of pawning. Unlike in the Gold Coast, in southern Nigeria even child-pawning was not outlawed explicitly until 1916 and not rigorously prosecuted until 1927. The result was a widespread resort to pawning in the early years of colonial rule. The incidence of pawning rose greatly (according to Oroge’s overview) before the administration took serious action against it in 1927. Pioneers of Nigerian cocoa-farming, such as J.K. Coker, a key figure in Agege Planters’ Union, relied heavily on iwofa.Footnote 85 Further north, in Ijesha, the outstanding pawn-master, Peel reported, “was Peter Apara who, according to his youngest son, had the service of upwards of 40–50 iwofa at times”, though more commonly pawns were used “in ones and twos”.Footnote 86 Nor was the use of pawn labour confined to export-crop producers, but included some of those who produced food for sale to those involved in cocoa production and marketing. Peel noted the case of a Yoruba commercial food-farmer who died in 1928 who had been considered “rich with up to 30 pawns”.Footnote 87

Slavery thus contributed to the inputs of labour for the cash-crop revolution of the colonial period. The role of first-generation slaves diminished most quickly. Slaves born in the household, on the other hand, being more integrated in the slave-owning society and without an original home to escape to, were most likely to stay and to keep working for their masters. Meanwhile pawning, long-established as it was, either continued alongside slavery until the simultaneous demise of both (Ashanti) or actually became much more common as a replacement for slave labour (Yorubaland). The latter trend turned out to be transitional.

The cash-crop “revolution” and the decline of slavery

The growth of export agriculture did much to determine the economic opportunities and risks facing slaves as they contemplated leaving their masters; and did much to decide the implications for the former masters. The influence of cash crops on slaves’ decisions has to be seen in the context of social and practical considerations. For instance, slaves seem to have been most likely to leave where they were present in large concentrations; and when they were relatively newly arrived, so that they could hope to find their kin and resume a life as a free member of a community, rather than having to start afresh on strangers’ terms. These conditions help account for the great Banamba slave exodus, to take the leading case.Footnote 88 Men, women and families left, especially men.Footnote 89 The tendency for first-generation slaves to be the quickest to leave did not always apply. The 1909 administrative report for the cercle of Kayes, in Mali, stated “It is only when [slaves] have accumulated some savings, acquired cattle, that they ask to return in the regions they came from.”Footnote 90 The decision to stay or go was indeed affected by economic risks and opportunities. A whole range of variations can be seen across the region.

In principle, the most economically attractive option was to become an independent cash-crop farmer (or farming household). This was open to those slaves who had originally been captured in areas suitable for export agriculture, providing they could re-establish their rights to land there. In Ashanti, slaves from what was now the Gold Coast Colony left relatively soon after the colonial government finally prohibited slavery in 1908, heading home to lands where cocoa growing was either established or being introduced. In both Asante (Ashanti) and Yoruba communities, as we have seen in Peel’s Ijesha case, some former slaves eventually became cocoa farmers in their own right. For some years at least, they were likely to need the patronage of their former masters, and provide him (as it usually was) with some labour; but this tended to dwindle, and become at most symbolic. In Asante some former slaves eventually became relatively wealthy, such that by the 1930s or at least 1950s they were no doubt among the high proportion of cocoa-farmers in Asante who hired labour. Meanwhile their social assimilation, though limited in that they were usually denied the chance to become chiefs, was assisted by a strong custom of not revealing people’s social origins. They could thus try to conceal their foreign and servile origins, with variable success.Footnote 91

In northern Nigeria, especially in Kano province, thousands of former slaves became smallholding peasants, growing groundnuts for sale. This outcome was encouraged by the colonial tax regime. For the British ended the exemptions from grain tax that many slave estates had enjoyed under the Sokoto Caliphate. This, and related tax reforms, gave masters an incentive to let their male slaves work on their own account, or ransom themselves, because the slave or former slave thereby became responsible for his own tax (the effect on female slaves was indirect but in practice similar). Also by their own initiative, thousands of slaves left their masters’ communities and established peasant households.Footnote 92

Meanwhile, or rather as early as the 1890s, many thousands of people held as slaves in the inland savannas of the western Sudan, and on the desert-edge, seem to have left their masters’ communities. Many joined the streams of migrants going into groundnut production in Senegambia. The annual report on French West Africa for 1910 stated that “former slaves of the Sahel descended in small bands into Senegal where they have covered the lands adjacent to the new Thiès-Kayes railroad with their plantings”.Footnote 93 Searing argues “that slaves from within the Wolof region took advantage of the same opportunities”. In their case they were already in, or near, groundnut-growing lands. “This seems the most likely explanation for the rapid decline of slavery in Kajoor and Bawol, where the slave populations seem to have evaporated without leaving a trace in the colonial archives.”Footnote 94

Leaving his master’s community, a self-emancipated slave could present himself to a landowner elsewhere as a free migrant in search of land to rent. Alternatively, he could join a peasant household in the junior status of an unmarried, dependent man. The first strategy would make most sense for first-generation slaves originally taken from beyond the groundnut basin, because free migration was normally seasonal, and a former slave could use the dry season to re-establish a home base. The second strategy would reduce the risks involved in staying all year in the basin, allowing some of the benefits of belonging to a household in return for dependent status. In both cases, the terms offered by local groundnut farmers would be similar to the work regime that slaves faced: giving the best part of their time to the work of the host/master.Footnote 95 Another option, noted by Swindell and Jeng in the Gambia, was that where slaves bought their freedom – as opposed to running away – the chiefs would allow them to cultivate unused land in the neighbourhood. That meant they could stay in the same community; but the previously unused land might be of relatively low quality.Footnote 96

In French Guinea (now the Republic of Guinea), as Emily Osborn has shown, rubber-tapping provided opportunities for former slaves during the early years of colonial rule. Osborn quotes a report by Auguste Chevalier, a French official and agricultural specialist, in 1910. “Chevalier explained that during an 1899 [journey] through the region, he had ‘met natives every day crossing through the bush, slaves fleeing or released sofas [slave soldiers] […] They were going to look for their natal villages to establish themselves there’.” Returning “in 1910, he noted […] : ‘These same individuals […] today […] have rebuilt their old villages; they have exploited the vines of rubber or kola plants. They have lived for more than ten years in a state of absolute peace and their families are secure’”.Footnote 97

For those slaves who wanted their own farms, rent-free, but who had no rights to land in an export-crop zone, there was the possibility of establishing food farms in their original home. For cash they would have either to plant whatever cash crop would grow, probably getting only slight returns because of soil quality or distance to market. Even in such a context, however, former slaves were in some cases able to return with valuable new knowledge or assets. Brian Petersen’s study of Buguni, in what is now southern Mali, found slaves returning home with different kinds of millet, rice, or maize; many brought back materials to plant fruit trees; others had worked as weavers, blacksmiths, or in other trades; or at least they brought the knowledge that farming groundnuts in Senegal was remunerative.Footnote 98 On the other hand, the results of these crop shifts were modest enough to be reversible: when the purchasing power of cotton producers dwindled in the Depression, there was a revival of pawning.Footnote 99

The final possibility, for slaves, was to stay in order to retain a degree of security, and perhaps a little property, and in expectation of less harsh treatment from the master in future.Footnote 100 Such household-level reform might happen either through direct negotiation, or if the master felt it expedient to be less demanding. With other slaves having run away, and with the option of buying new slaves closed by the suppression of the slave trade, masters had incentives to compromise. In Wuli, on the north bank of the Gambia river, the agricultural labour required of (non-court) slaves was reduced “from six to five and then to four days per week”.Footnote 101

Emancipation reduced inequality, but took unequal forms. It is generally thought that the majority of slaves were female.Footnote 102 But the labour-market opportunities for freed slaves were mainly for men. This applied both to the young adults joining groundnut-growing households in Senegal as dependent labourers and to the cocoa labour market in the Gold Coast Colony and Ashanti.Footnote 103 Female slaves were more likely to stay with their masters, not least because they were likely already to have had children with a free man. But for those slaves who stayed, female as well as male, the longer-term tendency was for them to achieve greater autonomy. In the more prosperous parts of the cash-crop economies, at least, women were often able to capitalize on the secondary economic effects of export agriculture – when these developed sufficiently. In Ashanti, for example, cocoa income was often spent in food and other local markets, providing cash-earning opportunities for traders (mostly women) and food-farmers (very often women).Footnote 104

The inequalities of emancipation operated along space and ethnicity as well as gender. For a former slave participating in cash-crop production, much depended on whether they did so as a local citizen, or as a stranger. The first migrant labourers to work on the cocoa farms of the Gold Coast Colony were often Ewes from southern Togoland, many of whom came from districts just as suitable for cocoa growing as those where they were employed. Some of them brought cocoa seedlings back home to plant for themselves. Thus, they could forsake the labour market for the produce market.Footnote 105 North of the Gold Coast Colony, in Ashanti, most of the migrant labourers came from the savanna. They therefore did not have the option of entering cocoa-farming back home. They and their successors continued to work for wages (or, increasingly, crop shares) in the cocoa belt, rarely achieving the ownership of a farm of their own.Footnote 106 Regional inequality was a marked feature of the cash-crop economies of twentieth-century Africa: cocoa economies generally being wealthier than groundnut or palm-produce producers, and cash-crop growing areas being better off than their labour-supplying hinterlands. The fortunes of former slaves more often reflected this pattern than qualified it.

Yet there was a huge gain for the labourers, arising from the fundamental economic effect of the spread of export agriculture. It brought West Africa’s lands more fully and more lucratively into production. Along with the population growth to which it gave financial support, it increasingly made land less abundant and labour less scarce.Footnote 107 In the abstract, this made labour power less valuable. But by the same token, it made it profitable for many masters to become employers. Thus, the slave trade was succeeded, over much of the region, by a consensual market for seasonal or annual labour. This gave migrant labourers opportunities not only to sell their labour – if they did not have the right kind of land in the right place to sell their produce – but also later to renegotiate and improve their contracts.Footnote 108

What of the masters? Those whose slaves stayed generally had to accept reduced economic returns on slave ownership; and even those returns were in long-term decline. Of those masters who lost their slaves, some had to contract their operations: their farming and/or trading activities were shrunk by loss of labour. This seems to have been a common experience in Igboland (in south-eastern Nigeria).Footnote 109 In what is now Mali, the Maraka elite of Banamba, shorn of their slaves by the exodus, had to make a profound adjustment: to performing their own work (making more intense use of self and family labour) and reducing their consumption, including their expenditure on religious institutions. In trade, with a reduced labour force, they lost market share.Footnote 110

In Guinea many of the former slave masters did rather better, becoming independent rubber traders, thereby avoiding having to labour for themselves once they lost their slaves. “For them, the ‘crisis’ of slave departures occurred not with the initial departure of slaves, but when the price of rubber plummeted in 1913.”Footnote 111 In handicrafts, in south-east Nigeria, the women cotton weavers of Akwete apparently adjusted to the end of slavery by relying on family labour, and, in respect of spinning, by using imported cotton yarn instead of local, hand-spun, yarn.Footnote 112

Others made the transition from masters to employers. That they could do so – where they could – showed that the economic conditions that had made markets for long-term labour impossible without some form of coercion, no longer existed. Where returns to labour in cash-crop farming were high enough, farmers could afford to hire labour. This did not apply to cotton or anything else in the more remote savannas. In contrast, it became very common with cocoa growers everywhere (though not all the time, depending especially on the producer price of cocoa).Footnote 113 In the case of cocoa, the capacity to hire labour reflected not only the price but also the nature of the crop. In planting cocoa trees, labour created a stock of capital, the returns on which could be used to pay for later rounds of labour services. In Nigeria, the same individuals who had been the largest users of pawn labour on cocoa farms took the lead in making the transition, and became the largest employers of hired labour. According to Agiri, the biggest cocoa farmer, J.K. Coker, “started as early as 1904 employing about 200 unskilled Yoruba labourers annually, with six or seven headmen”.Footnote 114 Oroge maintained that the majority of them were actually on the iwofa system, and that this was true of the Agege cocoa plantations generally.Footnote 115 But this does not contradict Agiri’s claim that “[t]he annual contract [in southern Nigerian agriculture] […] was developed on the Coker farms”.Footnote 116 In Ashanti too, cocoa earnings enabled masters of slaves and pawns, and chiefs who had summoned their subjects to make farms for them, to become employers instead. The relative smoothness of this transition was helped by the relatively high prices that generally characterized the pre-1914 era.Footnote 117

Abolition and economic growth

The prevailing resource mix had made slavery profitable during the pre-colonial nineteenth century. For economic growth, the main weakness of West African slave systems was the fact that new slaves were imported not from overseas, but from within the region. Therefore, while the inhabitants of the more powerful states were protected from slave raids, the size of the markets for their products was limited by the insecurity and losses of people and property that were imposed on neighbouring areas by slave raiding, and by wars financed by the capture and sale of slaves. From this starting point, let us consider the broad economic implications of the ending of slavery.

It can hardly be argued that abolition was essential to the expansion of cash-crop production that occurred from the 1890s through the 1920s. The original growth of groundnut and palm-oil exports before the European conquests proved that steady growth of output could be achieved using slave and pawn as well as family labour. Again, the various forms of coerced labour made a major contribution to the further growth and diversification of commodities and zones of production that occurred during the early colonial period. If cocoa farmers could hire labour in Ashanti and south-western Nigeria in the 1910s, this was to a great extent thanks to the proceeds of trees already planted by slaves and other coerced labourers.

Where slaves left suddenly and in large numbers, the immediate effects on output must have been negative; at least while the runaways made good their escape and found themselves ways of participating in the economy on new terms, often in new places. Lovejoy and Hogendorn have emphasized that flight of slaves was a major cause of the “economic dislocation” that led to famines “at different times in various parts of Northern Nigeria” between 1902 and 1908.Footnote 118

For export crops, consider Senegambian groundnuts in the late nineteenth century. The volume of Senegalese groundnut exports did not regain (and surpass) their 1882 level until 1898. Searing argues that this can only partly be explained by price falls, and that “the chaos created by the conquest and the flight of slaves in the period” also contributed.Footnote 119 A similar case can be made about the Gambia in the 1890s. As Table 2 shows, there was a sudden and drastic fall in exports from 1893 to 1895.

Table 2 The Gambia groundnut shock of the 1890s

Note: Gambian groundnut prices do not appear to be available for most of these years, so Senegalese ones are used instead (from Searing).

Sources: Swindell and Jeng, Migrants, Credit and Climate, pp. 23, 71, 101; Searing, “God Alone is King”, p. 199.

Swindell and Jeng attribute the fall to “weak groundnut prices and erratic rainfall”.Footnote 120 These are part of the story but, as Table 2 also indicates, not all of it. In May 1894, the travelling commissioner for the North Bank of the Gambia reported on slavery that “[t]he Jolas are settling this question by running away”.Footnote 121 This was presumably a response either to the British occupation of the previous year, or, perhaps more likely, to the new Slave Trade Abolition Ordinance, which preserved slavery but set a fee for slaves to ransom themselves and made slaves free on the death of their master. As in other parts of West Africa, some slaves immediately outdistanced the government action, literally. While the Mandingo slaves were staying, added the commissioner, “the Jolas […] will all make their escape sooner or later”.Footnote 122 Four years later he confirmed that the prediction had come true, at least for Jola men: “After the British occupation in ’93, all the male slaves principally Jolahs ran away, leaving behind only hereditary and old slaves, and female Jolahs.”Footnote 123 A high proportion of the slaves leaving their masters is another possible explanation for the drastic drop in groundnut exports, and the timing fits it better than the other explanations. Also, it was in the 1890s, according to Peter Weil’s fieldwork, that the number of days of agricultural work per week that was required of slaves in Wuli was repeatedly reduced.Footnote 124 This probably began after the Ordinance, in an attempt to stem the flight of slaves.

The combined effect of fewer slaves and shorter weeks would have reduced the masters’ output. When the former slaves managed to settle permanently, they would have resumed producing groundnuts, on their own or better terms. Hence, we would expect to see a sharp decline in exports followed by a probably equally sharp recovery. This is exactly what happened. The Gambian case illustrates what was probably a wider pattern: that while trends in export production responded to prices, rainfall and other conditions, mass departures of slaves would exert sharp downward pressure – temporarily.

A more enduring change for which the dwindling availability of slave labour was held responsible was the end of indigenous gold-mining by traditional methods in Ghana (an occupation that was the origin of the name “Gold Coast”). In 1931 the colonial chief census officer wrote that shafts made by traditional methods “are now no longer worked, as with the disappearance of slave labour the results would not possibly be sufficient to cover the expense”. In Ashanti, where the industry had lasted longest, village elders told a government anthropologist in 1925 “We have now stopped mining because it only pays when you have slaves.”Footnote 125 The fact that the same had already occurred in the late nineteenth century in the Gold Coast Colony may be related to the earlier abolition of slavery there. However, it is possible that the change of labour institution masked a shift in the structure of the economy, from traditional gold mining to export agriculture, that was occurring anyway. For if slave labour had continued to be available, it seems likely that masters would have re-directed it into cocoa production.

In the long term, the ending of slavery surely increased the growth potential of West African economies. There was the enormous gain by the ending of slave raiding, the “collateral damage” of which perpetuated the relative underpopulation of the region, and the threat of which prevented the cultivation of land in vulnerable areas (and left them more susceptible to tsetse fly infestation, and therefore to the livestock-killing animal version of sleeping sickness).Footnote 126 Again, while the slave trade was itself a labour market, duly channelling labour to where it was most valuable in market terms, the markets in voluntary labour services that replaced it surely performed that economic function more efficiently.

Whether slavery (as opposed to slave trading) and slave ownership were less efficient than the institutions that replaced them is much less certain. Slaves generally had some of their labour time available to themselves, and in principle they could keep any property they obtained.Footnote 127 It is also unlikely that masters allowed them to slack. In Sierra Leone in 1906 slaves were reported to work longer hours on the farm than free men.Footnote 128 Again, Cuvillier-Fleury assumed that masters enjoyed lives of indolence. That may have been true of some, but it hardly applies to the Juula traders of western Sudan, nor to their Hausa counterparts in central Sudan, whose work was conspicuously arduous and determined, even if they rode rather than walked. Nor does it apply to the Soninke entrepreneurs, who pursued an interlinked combination of agricultural, industrial, and commerical activities in the search for wealth.Footnote 129 Nor does it fit with the Asante moral economy of accumulation, subscribed to by both commoners and chiefs, in which there was always the incentive to acquire even more through the efforts of oneself – and one’s dependents, slaves included.Footnote 130 So while it is plausible that the end of slavery improved labour productivity, this is not entirely clear.

The purchase of a slave was an investment, a transaction in the capital as well as the labour market. In areas suitable for large livestock, notably in the middle Niger Valley, emancipation stimulated investment in cattle, sheep, and goats. In the process, according to Richard Roberts, the ownership of livestock was diversified, breaking down the pre-colonial tendency towards ethnic monopolies.Footnote 131 Both these related changes, in principle, would be conducive to long-term economic growth.

Swindell suggested that abolition, by causing a proliferation of domestic units as well as allowing more people to make their own decisions, may have led to higher fertility; with peasant families choosing to have more children for economic reasons than did larger, slavery-based establishments.Footnote 132 If that was so, it could have been a major economic benefit of emancipation, because it reduced the region’s historic scarcity of labour. As Swindell admitted, the issue is complicated and the argument speculative; but well worth future attention.

A final economic advantage of emancipation is that, irrespective of its intrinsic economic pros and cons, slavery was increasingly unacceptable in twentieth-century international relations. When Cadburys’, the Quaker-owned British chocolate manufacturer, stopped buying cocoa from San Thomé and instead started buying in the Gold Coast, between 1907 and 1909, it was in response to a scandal over “slave-grown” cocoa in the Portuguese colony.Footnote 133 It has become probably even more true since, that to have a coerced labour force exposes the economy to at least the risk of trade and investment boycotts.Footnote 134

A levelling process?

According to a much-debated thesis, most influentially put by Hopkins, the transition from the Atlantic slave trade to “legitimate commerce” in the pre-colonial nineteenth century saw the entry of small producers into production for export markets and undermined the economic position of the large merchants and rulers who had dominated the export of slaves.Footnote 135 The end of slave labour, and the transition from the internal slave trade to markets in labour hired for the season or year, can also be seen as entailing a shift of wealth and power from elites to small producers. As with the debate on the nineteenth century,Footnote 136 though, this generalization requires qualification. The economic premiss of Hopkins’s thesis applies in the colonial period too: that cash-crop production in West Africa had no significant economic advantages of scale, so that a small producer could supply a kilogram of groundnuts or cocoa beans as cheaply as a large producer. But, as in the preceding period, that was not the only determinant of the distribution of output and income. Moreover, it did not mean that larger producers were necessarily less competitive either.Footnote 137

In the region as a whole, the main direction of change in social and economic organization was the proliferation of independent farming households, relying mainly on free family labour. This emergence or enlargement of the peasantry was especially true of the savannas, from the groundnut basin of Senegal, through Mali and on as far as (though less so in) northern Nigeria.Footnote 138 In the forest zone too, many new, and relatively small, households were formed. In Ilorin, on the northern edge of Yorubaland, local economic opportunities were fairly restricted. So, whereas in Senegal the new peasant households could expect to profit directly from the cash-crop economy, beyond the cocoa belt in south-western Nigeria former slaves left their masters, not so much in the hope of making fortunes as of establishing a means of coping independently.Footnote 139 In general, households in relatively poor areas – whether within Yorubaland, and in the region generally – often relied on the new markets for long-term labour to secure cash incomes.

In northern Nigeria peasant autonomy was balanced by disadvantage, in that they suffered the financial burden of the regressive tax system that had encouraged masters to either free them or allow them to live and work alone. In the latter case, they had to pay a fee, murgu; and in all cases they were subject to direct taxation. On the other hand, very gradually, many of the slaves who had continued to cultivate for their masters acquired effective ownership of the usufructs.Footnote 140

The creation of hundreds of thousands of new households by people freed or freeing themselves from living as slaves in larger households headed by their master, or on plantations, clearly shifted the control of labour down the social scale. In some cases, “when the slaves left, the owners wept”. For south-eastern Nigeria, Don Ohadike argued that, unlike in the pre-colonial nineteenth century, when the Aro elite adapted with some success to the transition from the Atlantic slave trade to palm-oil exporting, “colonial Igboland is not a case where the old entrepreneurial class had adjusted to the new economic system, but one in which their death occurred before a new one was born”. When a new indigenous entreprenurial class eventually emerged, later in the colonial period, many of its members were former slaves or their descendants. The latter had often taken advantage of missionary education where the chiefs had not.Footnote 141 Meanwhile in Senegal, a new Muslim elite emerged, alongside that associated with the old slave-owning royal dynasties: the Murid order. Many of the people who settled as peasants in the villages that the Murids founded during the early colonial period were former slaves.Footnote 142 The peasants donated labour and cash to the scholarly leadership, but according to Searing, otherwise lived their economic lives in the same way as fellow Wolof households outside the order.Footnote 143

Finally, in certain other areas prior arrangements, economic geography, and colonial support enabled previously slave-holding elites to retain and reproduce their relatively strong economic positions after emancipation. We have already observed the capacity of Asante chiefs to give themselves a head start in the cocoa era, by having farms made for them by their subjects. More widely in cocoa-growing areas, the fact that this particular crop was capable of generating returns on labour sufficient to employ hired labour gave a long-lasting significance to the use of slave and pawns to make early cocoa farms. The energies of these human assets were thereby converted into new forms of capital – cocoa trees – that produced flows of income for their masters, enabling them to employ free labour after the slaves and pawns had left.

This legacy does much to explain the unequal distribution of income among cash-crop growers later in the colonial period, despite the absence of economic advantages of scale in production. Crucially, the local elites controlled the land; so that, as we have seen, migrants from the savanna could not acquire ownership of it.Footnote 144 It is worth noting that the individual who emerged as leader of African commercial farmers in colonial Côte d’Ivoire, and went on to become the first president of the independent republic, Felix Houphouet-Boigny, “by his own testimony, was from a former slave-owning, elite family”.Footnote 145

Conclusions

The pioneer literature on the cash-crop revolution overlooked the possibility that it was causally linked to the ending of slavery, because it tacitly assumed that slavery was unimportant in the late pre-colonial and early colonial economies of the region. Subsequent research revealed that there was extensive commodity production in the decades before colonial rule, for internal as well as external markets, and that enslavement and the internal slave trade was the main means of recruiting labour from outside one’s existing household. Indeed, with land abundant and labour scarce, it is unlikely that markets for long-term labour would have existed without the coercion that generated slaves and human pawns.

In this setting, it is not surprising that the expectation of some writers that abolition was necessary for the rapid growth of cash crops turns out to be unfounded. Slave labour had been fundamental to the expansion of commodity production in various parts of the region during and after the decline of the Atlantic slave trade and before the European conquests. Insofar as economic considerations entered the internal policy debates of the colonialists, they pointed firmly against the rapid and compulsory freeing of slaves. Rather, the colonial administrators’ approach was usually gradual, and often took the form of making slavery legally unenforceable rather than making it a crime. Slave (and pawn) labour duly made an important contribution to the growth of export agriculture in the early years of several colonies. When and where slaves departed in large numbers – often fleeing at their own initiative – the result was often to dislocate economic activity. The colonial interventions, intentionally moderate though they were, crucially weakened the coercive basis for slavery, and thus undermined the institutional framework inherited from before colonial rule. In the long term, however, the abolition of the slave trade, and indeed of slavery itself, surely increased the economic potential of the region.