Mennonite Plautdietsch (ISO 639–3: pdt) is a West Germanic (Indo-European) language belonging to the Low Prussian (Niederpreußisch) subgroup of Eastern Low German (Ostniederdeutsch), a continuum of closely related varieties spoken in northern Poland until the Second World War (Ziesemer Reference Ziesemer1924, Mitzka Reference Mitzka1930, Thiessen Reference Thiessen1963). Although its genetic affiliation with these other, now-moribund Polish varieties is uncontested, Mennonite Plautdietsch represents an exceptional member of this grouping. It was adopted as the language of in-group communication by Mennonites escaping religious persecution in northwestern and central Europe during the mid-sixteenth century, and later accompanied these pacifist Anabaptist Christians over several successive generations of emigration and exile through Poland, Ukraine, and parts of the Russian Empire. As a result of this extensive migration history, Mennonite Plautdietsch is spoken today in diasporic speech communities on four continents and in over a dozen countries by an estimated 300,000 people, primarily descendants of these so-called Russian Mennonites (Epp Reference Epp1993, Lewis Reference Lewis2009).

Linguistic research on Mennonite Plautdietsch is extensive, spanning the past eight decades. General grammatical descriptions are provided by Quiring (Reference Quiring1928) for a 1920s-era Chortitza Colony variety; Baerg (Reference Baerg1960) for a single Molochnaya Colony variety spoken in Kansas; Mierau (Reference Mierau1964) for several unspecified varieties spoken in western Canada; Avdeev (Reference Avdeev1965), Kanakin & Wall (1994) and Nieuweboer (Reference Nieuweboer1999) for several Altai region varieties spoken in western Siberia; and Siemens (2012) for a diachronically-oriented perspective on the development of Mennonite Plautdietsch more generally. Both Goerzen (Reference Goerzen1950, 1952) and Lehn (Reference Lehn1957) present studies on phonology and phonotactics, focusing on post-1920 Chortitza Colony varieties spoken in western Canada, while Brandt (1992) describes the phonology of several northern Mexican Plautdietsch varieties related historically to Canadian varieties. Perhaps the most detailed studies of Mennonite Plautdietsch phonology and morphology are Jedig (Reference Jedig1966) for western Siberia and Buchheit (1978) for Nebraska, the former study tracing the development of the phonology from its Middle Low German roots, the latter concentrating on synchronic phonological and morphological processes. Naiditch (Reference Naiditch and Braun2001, 2005) follows Jedig (Reference Jedig1966) in describing the diachronic development of the consonant and vowel systems of an unspecified variety of Mennonite Plautdietsch, while Wiebe (Reference Wiebe1983, 1993, a.o.) presents a series of psycholinguistically oriented studies on orthographic representation and phonological knowledge with a community in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. Although substantial research from both synchronic and diachronic perspectives addresses phonological organization, the authors are not aware of any phonetic descriptions of any variety of Mennonite Plautdietsch to date.

The present illustration concentrates on one lesser-studied variety of Mennonite Plautdietsch commonly associated with the Old Colony (formerly Reinländer) Mennonites, members of one conservative Mennonite denomination who immigrated to western Canada from present-day Ukraine primarily in the 1870s (see Redekop Reference Redekop1969, Reger & Plett Reference Reger and Plett2001). As a result of repeated rounds of mass emigration on the part of Canadian Old Colony Mennonites to Latin America during the twentieth century, significant Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch speech communities exist today in Mexico, Paraguay, Belize, and Bolivia. Other varieties of Mennonite Plautdietsch are attested in Canada, as well, and have received some previous linguistic attention (e.g. Goerzen Reference Goerzen1952, Mierau Reference Mierau1964, Moelleken Reference Moelleken1972). This description is based on the speech of the second author, born in 1926 in Blumenheim, Saskatchewan. The second author was raised in an Old Colony Mennonite home and acquired Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch as his first language (see Driedger Reference Driedger2011). His translation and production of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ in Mennonite Plautdietsch is provided below.

Consonants

Mennonite Plautdietsch has 29 phonemic consonants, as illustrated by the above word list. Where available, Mennonite Plautdietsch items were selected to illustrate the consonantal contrasts before /o/ in a stressed syllable, preferably in word-initial position. In cases when this environment was not available, a non-initial stressed syllable was sought which presented the necessary consonant before a nuclear /o/ (e.g. Jitoa /jɪ.ˈtoa/ ‘guitar’). If neither of these conditions could be satisfied, items were selected where the relevant consonant preceded /a/ (e.g. /s/ in Massa /ˈma.sa/ ‘knife’, /x/ in Pracha /ˈpra.xa/ ‘beggar’). These environments were sufficient to demonstrate all consonantal phonemes except /lʲ/, which is only attested word-finally in Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch (e.g. Baulj /baʊlʲ/ ‘bellows’, contrasting with Baul /baʊl/ ‘ball’). While the glottal stop is treated here as an independent phoneme (see Siemens Reference Siemens2012: 73), this segment appears only as a syllabic onset in lexemes which would otherwise lack one (e.g. oam /ʔoam/), and could thus potentially be treated as a phonetic segment, instead.

Notably, the phonemic inventory of Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch contrasts palatalized and non-palatalized velar stops, as in koasch /koaʃ/ ‘healthy’ vs. Kjoasch /kʲoaʃ/ ‘cherry’, Hack /hak/ ‘hoe’ vs. Hakj /hakʲ/ ‘hedge’. While /kʲ/ occurs frequently in both syllable-initial and final positions, /ɡʲ/ is significantly more restricted, rarely occurring outside of syllabic codas and in relatively few lexical items overall. Moreover, /ɡʲ/ only infrequently provides the basis for any phonemic contrast: the word list provided in Epp (Reference Epp1996) presents only rikj /rɪkʲ/ ‘rich’ vs. Rigj /rɪɡʲ/ ‘back (body part)’, and Akj /akʲ/ ‘corner’ and Agj /aɡʲ/ ‘edge of cloth, fringe’ as contrastive pairs. In other varieties of Plautdietsch, these same segments are realized as [c] and [ɟ] (Siemens Reference Siemens2012: 93–98) or [tʲ] and [dʲ] (Reimer, Reimer & Thiessen 1983: 24), respectively. The presence of these phonemic palatalized velar stops is rarely encountered in related Germanic languages. Siemens (Reference Siemens2003, 2012) suggests that these stops are an areal feature indicative of historical membership in the Baltic Sprachbund, while Naiditch (2005) and others trace these phonemes’ emergence through regular diachronic sound changes, while not ruling out contact influences altogether. Palatalized non-velar stops may also occur when followed by /j/, as in Eedjen /əɪdʲən/ ‘gutters’, and may be part of a larger palatalization process.

Allophonic variation is reported between an alveolar trill [r], an alveolar tap [ɾ], and a retroflex approximant [ɹ] for /r/ in some varieties of Mennonite Plautdietsch, with the trill and tap occurring in free variation and the retroflex allophone only appearing in non-intervocalic coda position. This variation was first noted for speakers of Mennonite Plautdietsch in Mexico by Moelleken (Reference Moelleken1966, 1993), who argues on the basis of comparative research on contemporary non-Mennonite varieties of Plautdietsch that the retroflex approximant is not a recent innovation prompted by contact with English. Given the historical relationship between the Mennonite Plautdietsch speech communities in Mexico and their source communities in Canada, it is not surprising to find such variation attested in the Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch represented in the speech of the speaker described here (e.g. Däaren [de.əɹn] ‘doors’, foahren [fo.əɹn] ‘to drive’, Korn /kɔɹn/ ‘corn, maize’). The [ɹ] allophone is reportedly a sociolinguistically-marked variant associated with this particular variety and is subject to commentary by other Mennonite Plautdietsch speakers in Saskatchewan (Jake Buhler, p.c.).

Unlike several other, related West Germanic languages, word-final obstruents do not demonstrate final devoicing, maintaining phonemic contrasts in this environment; cf. beed /bəɪd/ ‘Bid!’ (2sg imper) vs. Beet /bəɪt/ ‘beet’, weed /wəɪd/ ‘Weed!’ (2sg imper) vs. weet /wəɪt/ ‘knows’.

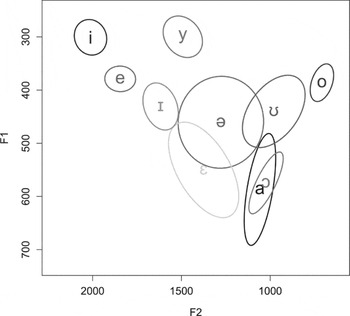

Mennonite Plautdietsch has 10 phonemic vowels, as illustrated in the vowel chart below and in the F1-F2 vowel space plot in Figure 1. Considerable variation exists between varieties of Mennonite Plautdietsch in their realization of the phonemic vowel inventory, although these distinctions remain poorly documented. The following concentrates on the realization of vowel phonemes in Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch, leaving phonetic comparison with other varieties of Mennonite Plautdietsch as a topic for further research.

Figure 1 F1-F2 plot of vowels from a combination of words and non-words (approximately 20 tokens per vowel), produced with the phonTools package in R (Barreda Reference Barreda2012).

Vowels

While the distinction between monophthongs is presented here as being primarily a qualitative one, quantitative differences are also observed, with the mean durations of /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /y/ before /t/ and /d/ in word-initial, stressed syllables all being longer than those of /ə/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ɔ/, and /ʊ/ in the speech of the second author. This may suggest that vowel quantity may serve as an additional cue to phonemic identity, in addition to the qualitative differences noted below.

Monophthongs in Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch maintain a contrast in roundness only in the front high vowels (e.g. Biet /bit/ ‘a bite’ vs. buut /byt/ ‘builds’), with the absence of a corresponding high back rounded vowel phoneme /u/ in this variety explained historically as the result of so-called ‘spontaneous palatalization’ (see Naiditch 2005: 80). Such asymmetry in the inventory is not paralleled among the diphthongs, however, where /u/ is found in items such as wua /vua/ ‘where’, and is distinct from /ya/ in items such as Buua /bya/ ‘builder’. Monophthongs are also often centralized in unstressed position, as in the reduction of /a/ to [ə] in romma /ˈɾɔ.ma/ [ˈɾɔmə] ‘around’ in connected speech.

The realization of several of these vowel phonemes in Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch differs in some respects from what would be anticipated from the IPA symbols used to represent them here. In the speech of the second author, the front vowels /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ have lowered to [ɛ] and [æ], respectively, and /ʊ/ has centralized to [ɵ], leaving the entire high back vowel space empty of monophthongs. Notably, as seen in Figure 1, no difference in F1 or F2 values for /a/ and /ɔ/ is found in this variety, with these phonemes being realized as [ɐ] or [ɑ]. Instead, this phonological distinction is likely maintained as a difference in length and, to a lesser extent, F3 values. In a small sample of these vowels appearing in stressed, word-initial syllables before /t/ and /d/ (n = 36), instances of /a/ demonstrate almost twice the mean duration (291 ms) of instances of /ɔ/ (158 ms). To the authors’ knowledge, a phonemic length cue in any of the Plautdietsch monophthongal vowels has not been reported in the previous literature, although occasional reference is made to the (non-phonemic) length characteristics of /a/ (see Jedig Reference Jedig1966).

Diphthongs

Mennonite Plautdietsch has eleven phonemic diphthongs:

Reduction of the /a/ off-glide in diphthongs is occasionally found in closed syllables and in rapid speech, as in woamen [ˈvoəmən] ‘warm:m.sg.acc’ and Nuadwind [ˈnuədvɪnt] ‘north wind’ (see Buchheit Reference Buchheit1978: 40–41). The variety of Canadian Mennonite Plautdietsch considered here does not provide evidence of the phonemic contrast reported in Epp (Reference Epp1996) for other varieties between /iə/ (Biee /biə/ ‘bees’; contrast not present in this item in Canadian Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch) and /ia/ (Bia /bia/ ‘pillow case’). Similarly, differences are reported across varieties of Mennonite Plautdietsch not only in the phonemic composition of the diphthong inventory, but also in their realization, with some varieties noting reduction of /aʊ/ to /ɒ/ or /ɔ/ (see Kanakin & Wall Reference Kanakin and Wall1994, Moelleken Reference Moelleken1966).

The phonemic status of several of these diphthongs deserves closer attention. The distribution of /eɔ/ is predictable in this variety of Canadian Mennonite Plautdietsch, appearing before non-palatalized velar consonants, e.g. Böagen /ˈbeɔɣən/ ‘bow’, möaken /ˈmeɔkən/ ‘to make’, but stoakjste /ˈʃtoakʲstə/ ‘strongest’. It could thus be seen as an allophone of /oa/, which is consistent with the distribution of [oa] across both prevelar and non-prevelar contexts in other varieties of Plautdietsch where /eɔ/ (or, in varieties with a rounded variant of this phoneme, /œa/) is not attested (see Loewen Reference Loewen1998). Exceptions to this generalization exist, however, as in Joakob ‘Jacob’ (although the /eɔ/ variant of this form is also attested, i.e., Jöakob), motivating treatment as a separate phoneme. As well, the phoneme /uɪ/ is apparently restricted in this variety to a single lexical item, the interjection fuj ‘Yuck!’.

Triphthongs

Little consensus exists between previous analyses of triphthongs, which are often discussed with diphthongs. With one exception noted below, all triphthongs in this variety involve a final off-glide /ɪ/, which some have analyzed as coda /j/.

Monosyllabic contrasts between diphthongs and purported triphthongs are rare but identifiable, as in wäa /vea/ ‘who’ vs. Wäaj /veəɪ/ ‘roads’, wea /via/ ‘was’ vs. Weaj /viəɪ/ ‘cradle’, and Boa /boa/ ‘bear’ vs. Boaj /boəɪ/ ‘mountains’, as seen in the above wordlist. It is typical for orthographies and phonological analyses of Canadian Mennonite Plautdietsch to recognize at least the triphthong /əɪa/ as distinguishing sets of minimal pairs such as Beea /bəɪa/ ‘beer’, Bia /bia/ ‘pillow case’, and Bäa /bea/ ‘berry’; vea /fəɪa/ ‘four’, Fia /fia/ ‘fire’, and väa /fea/ ‘before’; and Heea /həɪa/ ‘honey (term of endearment)’, hia /hia/ ‘here’, and häa /hea/ ‘hither’. For the second author, however, this triphthong is typically perceived as two syllables (e.g. /bəɪ.a/ Beea ‘beer’), as is the case with /oəɪ/, leaving the monosyllabic status of these two vowel sequences in question.

Whereas other Canadian and American varieties have maintained a distinction between /əɪa/ and /ia/ consistently, the variety of Old Colony Canadian Mennonite Plautdietsch considered here preserves the contrast only in a limited number of lexical items, following an earlier merger of *eea and *ia to /ia/. This merger appears characteristic not only of the present variety, but also of most varieties spoken by descendants of the earliest Mennonite emigrants to the Americas from the Chortitza and Bergthal colonies, as is apparent in the absence of this contrast from the phonemic inventory of Mexican Old Colony Mennonite Plautdietsch found in Moelleken (Reference Moelleken1966). Phonemic descriptions of contrasting non-merged Canadian and American varieties are found in Goerzen (Reference Goerzen1950), Baerg (Reference Baerg1960), Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Reimer and Thiessen1983), Epp (Reference Epp1996), Loewen (Reference Loewen1998), and Neufeld (Reference Neufeld2000). Unlike several of these non-merged Canadian varieties, the variety considered here lacks the triphthong /əʊa/ altogether (see Loewen Reference Loewen1998: 136–137).

Stress and intonation

Primary stress is generally predictable based on the morphological structure of the item, falling on the first non-prefix syllable. Verbs ending in -earen represent an exception, with the penultimate syllable receiving primary stress, e.g. passearen /pə.ˈsia.ɾən/ ‘to happen’, opperearen /ɔ.pə.ˈɾia.ɾən/ ‘to operate’. Similarly, some borrowed lexemes show non-morphologically determined stress patterns, such as Perischkie /pə.ɾɪʃ.ˈki/ ‘pirozhki, fruit-filled pastries’ (< Rus. пирожки, Ukr. пиріжки) and Warenikje /və.ˈɾɛ.nɪ.kʲə/ ‘perogies’ (< Ukr./Rus. вареники); as do occasional items in the native Plautdietsch lexicon, such as (han) kefoojen /kə.ˈfəʊ.jən/ ‘to throw down forcefully’ and unjarenaunda /ˌʊ.ɲa.ɾəˈnaʊn.da/ ‘amongst, amidst, mixed’. Stress may be contrastive, as in the following examples:

While stress is comparatively well documented in existing Mennonite Plautdietsch dictionaries and grammatical sketches, intonation remains without any detailed analytical treatment to date. Baerg (Reference Baerg1960: 68–87) offers an impressionistic description of the intonation system of Mennonite Plautdietsch, providing hand-illustrated intonation contours for several sentence types (e.g. information and polar questions) and focus conditions. Mierau (Reference Mierau1964: 26–28) likewise briefly notes distinctive intonation contours correlating with declarative, interrogative, and imperative modes, though acknowledging that this characterization is ‘admittedly an oversimplification’ (p. 28) and that intonation in Mennonite Plautdietsch represents an area for further dedicated research. The sentences listed below, all variations of Jehaun haud ‘en oolet Peat ‘John had an old horse’ and Haud Jehaun ‘en oolet Peat? ‘Did John have an old horse?’, illustrate the prosodic contours commonly associated with neutral declarative statements (falling intonation), contrastive focus (pitch peak on contrasts), and clarification and polar questions (falling intonation with rise on last syllable).

Transcription of recorded passage

There is no single, standardized orthography for Mennonite Plautdietsch at present with general acceptance across all diasporic speech communities. Several distinct standard orthographies have been proposed, and appear to have converged in many respects upon similar conventions for representing phonemic contrasts common to most varieties (Reimer Reference Reimer1982, Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Reimer and Thiessen1983, Epp Reference Epp1996, Loewen Reference Loewen1998, a.o.; see Nieuweboer (Reference Nieuweboer1999: Chapter 6) for an overview of Plautdietsch orthographies). In the absence of an accepted orthographic standard for this variety, however, and in light of the sometimes controversial nature of orthographic choices in Mennonite Plautdietsch speech communities (see Cox Reference Cox, Newman, Baayen and Rice2011), the passage from the ‘North Wind and the Sun’ is presented below in both the orthography originally chosen by the second author, as well as in the Plautdietsch adaptation of the Sass orthography outlined in Epp (Reference Epp1996).

/de ˈnuədvɪnt ɛn de zɔn ˈʃtɾəɪd![]() zɪkʲ | veə dɑʊt ˈʃtoəkʲstə viɑ | ɑʊs əɪn ˈfəʊtjɛɲa mɛt ən ˈvoəmən ˈmɑʊnt

zɪkʲ | veə dɑʊt ˈʃtoəkʲstə viɑ | ɑʊs əɪn ˈfəʊtjɛɲa mɛt ən ˈvoəmən ˈmɑʊnt![]() | ˈɛnjəˌvɛkəlt ˈʔɑʊnkʲɛɪm | zɛɪ bəˈzɔnən zɪkʰ | dɑʊt dɛɪ | veə dem ˈfəʊtjɛɲa dɑʊt ˈiəʃtə vʊd ˈkʲɛnən zin ˈmɑʊnt

| ˈɛnjəˌvɛkəlt ˈʔɑʊnkʲɛɪm | zɛɪ bəˈzɔnən zɪkʰ | dɑʊt dɛɪ | veə dem ˈfəʊtjɛɲa dɑʊt ˈiəʃtə vʊd ˈkʲɛnən zin ˈmɑʊnt![]() ʔytɾaˑkʲən ˈmeʌkən | dɑʊt ˈʃtoakʲstə vʊd ˈzɛnən | dɑn pyst de ˈnuədvɪnt zə ˈzɛɪa ɑʊs hɛɪ kʊn | obə jə ˈdɔla hɛɪ pyst | jə ˈdɔla ˈvɛkɛld de ˈfəʊtjɛɲa zin ˈmɑʊnt

ʔytɾaˑkʲən ˈmeʌkən | dɑʊt ˈʃtoakʲstə vʊd ˈzɛnən | dɑn pyst de ˈnuədvɪnt zə ˈzɛɪa ɑʊs hɛɪ kʊn | obə jə ˈdɔla hɛɪ pyst | jə ˈdɔla ˈvɛkɛld de ˈfəʊtjɛɲa zin ˈmɑʊnt![]() ˈɾɔma zɪkʲ | ˈɛntliç jəɪf de ˈnuədvɪnt noˑ | dɑn ʃəɪn de zɔn voəm | ɛn fuəts tɾɔk de ˈfəʊtjɛɲa zɪkʲ den ˈmɑʊnt

ˈɾɔma zɪkʲ | ˈɛntliç jəɪf de ˈnuədvɪnt noˑ | dɑn ʃəɪn de zɔn voəm | ɛn fuəts tɾɔk de ˈfəʊtjɛɲa zɪkʲ den ˈmɑʊnt![]() yt | ɔn zəʊ mʊst deɪ ˈnuədvɪnt ˈtəʊʃtoˑnən dɑʊt de zɔn dət ˈʃtoəkʲstə ˈviɑ/

yt | ɔn zəʊ mʊst deɪ ˈnuədvɪnt ˈtəʊʃtoˑnən dɑʊt de zɔn dət ˈʃtoəkʲstə ˈviɑ/

Original orthography (Driedger Reference Driedger2011)

Dee nuad Wint onn dee Sonn streeden sikj, wäa daut stoakste wia, auss een Footjänga met een woamen Mauntel enjewelkjet aun kjeem. Sie besonnen sikj, daut dee, wäa däm Footjänja daut ieschta wud kjennen sien Mauntel üttrakjen mäaken, daut stoakste wud sennen. Donn püst dee nuad Wint soo seea auss hee kun, oba je dolla hee püst, je dolla wekjeld dee Footjänga sien Mauntel romma sikj. Entlijch jeef dee nuad Wint no. Donn scheen dee Sonn woam, onn fuats trock dee Footjänga sikj dän Mauntel üt, onn so musst dee nuad Wint too stonen, daut dee Sonn daut stoakste wia.

Sass orthography (Epp Reference Epp1996)

De Nuadwind un de Sonn streeden sikj, wäa daut stoakjste wea, aus een Footjänja met een woamen Mauntel enjewekjelt aunkjeem. Se besonnen sikj, daut dee, wäa däm Footjänja daut easchte wudd kjennen sien Mauntel uttraikjen möaken, daut stoakjste wudd sennen. Donn puust de Nuadwind soo sea aus he kunn, oba je dolla he puust, je dolla wekjeld de Footjänja sien Mauntel ‘romma sikj. Endlich jeef de Nuadwind noh. Donn scheen de Sonn woam, un fuats trock de Footjänja sikj dän Mauntel ut, un soo musst de Nuadwind toostohnen, daut de Sonn daut stoakjste wea.