And the Injun goes “How!”: Representations of American Indian English in white public space

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 January 2006

Abstract

This article describes linguistic features used to depict fictional American Indian speech, a style referred to as “Hollywood Injun English,” found in movies, on television, and in some literature (the focus is on the film and television varieties). Grammatically, it draws on a range of nonstandard features similar to those found in “foreigner talk” and “baby talk,” as well a formalized, ornate variety of English; all these features are used to project or evoke certain characteristics historically associated with “the White Man's Indian.” The article also exemplifies some ways in which these linguistic features are deployed in relation to particular characteristics stereotypically associated with American Indians, and shows how the correspondence between nonstandard, dysfluent speech forms and particular pejorative aspects of the fictional Indian characters subtly reproduce Native American otherness in contemporary popular American culture.I would like to thank the Woodrow Wilson Foundation and the University of Michigan for their support. This manuscript has also benefited from the following individuals' comments and suggestions: Gerald Carr, Eve Danziger, Philip Deloria, Joseph Gone, Jane Hill, Judith Irvine, Webb Keane, William Leap, Bruce Mannheim, and the anonymous reviewer. For their time and effort, I am truly grateful. All errors are my own.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2006 Cambridge University Press

INTRODUCTION

In the popular 1997 movie Con Air, starring Nicholas Cage and John Malkovich, a wrongly accused convict on board a prisoner transport flight (“Con Air”) witnesses a highly racialized attack(West 1997):

Even though the ethnic identity of the unnamed character isn't spelled out for the audience, it is clear that he is an American Indian (Native American). Curiously, it is not he himself who projects this identity, but rather the commentary and actions of Parker, an African American character, that unambiguously define this character as Indian. In doing so, Parker draws on a body of preexisting “Hollywood Indian” racial characterizations that are a part of “white public space” (Hill 1998).1

I use the terms “Hollywood Indian,” “Hollywood Injun” or “White man's Indian” when referring to stereotyped images of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and “Native American,” “American Indian,” or “Indian” when referring to indigenous peoples themselves in order to reinforce the distinction between “American Indian English,” which refers to a variety of English dialects, and “Hollywood Injun English,” which I define as a stereotypic non-Native fictional representation of American Indian speech.

Such racialized representations in film and other media have been the object of extensive analysis. Some of the most frequent representations portray American Indians as timeless, silent, savage Plains warriors (Churchill 1998; see also Berkhofer 1978, 1988), as in the allusions in Pinball's monologue above. Most linguistic research on American Indian representation has focused on the language used to describe Indians and not on their imagined speech.2

With the growing concern for transforming, altering, or eradicating homogeneous Indian representations, many researchers have begun to focus on the deconstruction and reconstruction of these images. This research has gone in three directions: pejorative images in literary and historical accounts (Cassuto 1997, Churchill 1998, Deloria 1998, Dilworth 1992, Lewis 1988, Macaruso 1984, Mieder 1993, Sawaya 1991); racially loaded terminology (Forbes 1995, Krishnamurthy 1996, Yellow Bird 1999; see also Bataille 2001); and analyses of the objectification of the “Indian” in public and popular domains, such as the media (Berkhofer 1978, 1988; Churchill et al. 1978; Churchill 1998; Ewers 1965; Green 1988a, 1988b; Kilpatrick 1999; King 1998; Mihesuah 1996; Nason 2000; Purdy 2001; Reed 2001; Rollins & O'Connor 1998; Stern & Stern 1993; Strong 1996, 1998; Sturm 2000; see also Bataille 2001). Throughout this literature, two dominant themes surface: the distinction between the “good” and the “bad” Indian, and the distinction between the “white” and the “nonwhite.” The relationship between these two themes predictably relates the “good” Indian with “whiteness” and the “bad” Indian with “Otherness.”

This article contributes to the work that critically assesses images of indigenous peoples produced by a dominant majority, expanding on previous research by focusing on language and, more precisely, on fictional representations of speech, and asking the following questions: How has Native American speech been imagined and represented in white public space? What linguistic features are highlighted and reproduced in this fictional dialogue? And in what ways do these fictive linguistic portrayals racialize and denigrate contemporary Native Americans? To answer these questions, I analyze the performed speech of Indian characters in eight films, three television episodes from two popular shows, and two contemporary greeting cards – a small sample, but illustrative of the limited repertoire Indian characters have to draw from. Emerging from this analysis is a description of a style of speech that I call “Hollywood Injun English” (henceforth HIE), a composite of grammatical “abnormalities” that marks the way Indians speak and differentiates their speech from Standard American English (SAE).

The first section grammatically analyzes Hollywood Injun English. It shows the ways in which HIE deviates from some standard variety of American English. The second section compares HIE with varieties of “real-life” American Indian English (AIE). Beginning with early pidgin varieties described by authors, adventurers, and captives and moving through the analysis of contemporary styles of AIE as described by linguists, we see that white public space offers a limited set of tokens to serve as indexes of “Indianness.” After having identified the grammatical structure of HIE and to some extent its origins, the third section analyzes two scenes from two different films to show how this linguistic template articulates with the images being portrayed in these films. However, while the HIE style can index many specific pejorative or demeaning characteristics, a full analysis of these is more than can be accomplished here. The fourth section discusses the ways in which this HIE style covertly perpetuates a racialized and racist image of Native North Americans.

Whether or not Indian characters are still being written as simple noble savages, subtler stereotypical attributes are still being referenced by actors attempting to sound like “authentic” (Hollywood) Indians. As they perform, they draw on and reproduce a static, monolithic imagery of Native voices. Thus, HIE is a good example of what Judith Irvine and Susan Gal have called “linguistic images,” “images in which the linguistic behaviors of others are simplified and seen as if deriving from those persons' essences rather than from historical accident” (2000:39). These “linguistic images” are also part of a larger national U.S. imaginary that routinely portrays minority (and immigrant) speech styles in a dysfluent, “Othered” fashion. And because these racialized styles of speech are an extremely salient and naturalized part of cultural representations, they can be readily performed by both children and adults in the United States (Andersen 1992), suggesting that we are socialized early on to practice linguistic segregation. These linguistic images contribute to the construction of the dominant white public as being indigenous because it is linguistically unmarked and “correct,” thus serving to erase Native North American diversity, primacy, and contemporary presence.3

Throughout the rest of this film, the only other scene that the Indian character is visible in is when, having survived Pinball's fire, he is killed by the DEA officials.

HOW! WHITE MAN: THE GRAMMAR OF HOLLYWOOD INJUN ENGLISH

Linguistic anthropologists and other linguists often talk about styles of speech, speech registers, or ways of speaking. In such cases they are usually referring to nonconventionalized forms of speech used in everyday conversation, not “abnormal types of speech” (for an exception see Sapir 1958 [1915] on Nootka; see also Basso 1979). Here, however, the focus is on just such a speech style, one that underscores and reinforces certain aspects of a generic Indian image.4

Following Mendoza-Denton 1999 (see also Bell 1984, Eckert & Rickford 2002, Irvine 1985), I would argue that HIE is a style of speech (as opposed to a register, dialect, genre, etc.) because it is deviant, mutable, self-consciously constructed, and extremely concerned with connecting to the audience and the audience's imagination of Indians (as opposed to invoking a particular situation or context, it elicits a particular memory or romanticized idea of Indianness).

With respect to Native American speakers' perceptions of other community members' speech, some people find that these public representations are exactly what they hear – a substandard form of English – and these people are critical of those who use any AIE variety. However, these critics themselves have chosen not to speak any AIE variety and tend to be proud of the fact that they speak a standard English dialect.

Berkhofer 1978, 1988 makes a similar observation with respect to the themes or images surrounding the “white man's Indian.” He notes that “along with the persistence of the dual image of the good and bad and general deficiency went a curious timelessness in the defining of the Indian as other” (1988:528). So, throughout the various transformations Indian images underwent, particular dualities and contrasts remained. The same can be said of the linguistic side of the imagery.

As we will see, the grammatical structure of HIE parallels quite closely that of “foreigner talk” as discussed by Ferguson (1996 [1971]). What marks the speech as HIE, however, is the deployment of certain phrases and lexical items found only in HIE and derived from various Native American languages and historical speeches and treaties performed by American Indian individuals (Berkhofer 1978:88, 220–21; Marsden & Nachbar 1988:608). This, coupled with other features, transforms the generic foreigner talk into the more specific Hollywood Injun talk. These are some of the resources actors draw on to enhance the portrayal of Indianness.

The distorted representations of American English that serve to mimic Native American speech (linguistic structures that non-AIE speakers can easily produce) have distinct patterns in prosody, morphosyntax, and lexicon (referring in particular to lexical borrowings and figurative phrases). Phonologically, Hollywood Injun English sounds like standard American English. There are only four utterances in the data that distinctly differ from some Standard American English pronunciation.7

Leechman & Hall 1955 and Miller 1967 actually provide some phonological generalizations for AI(P)E based on the linguistic representations in texts.

Changes in voice quality can sometimes be used to identify IE, as in an Indian chief speaking in a deeper, throatier voice or Pinball Parker's shift in voice quality in the opening example. This is true for all cases of IE, though. This is also a primary difference between IE and Mock Spanish, where phonological alterations play an integral part in this mimicked representation (see Hill 1993a, 1993b, 1995), perhaps because people hear different dialects of Spanish spoken whereas few people have heard or are even aware of the fact that there are many dialects of American Indian English.

The abbreviations for the sources are the following:

All the examples in (2) show extensive use of pauses, as well as pausal lengthening. They also reveal that the pause can be placed almost anywhere, either at a phrasal boundary or at a word edge. For example, in (2b), the pauses break up the phrase to humiliate him, with pauses at both edges of the word humiliate. The atypical use of pauses has a leveling effect on intonational contours, which creates a ponderous, monotonic pace suggestive of a lack of fluency (or a type of ungrammaticality), especially in those cases where the pause is not placed at a phrasal or syntactically defined constituent boundary.

Though often used to indicate a nonnative, incompetent speaker of English, in other instances this ponderous style may be used to represent an eloquent speaker performing oratory. Sometimes this oratorical style occurs within dialogue. In these cases, the style of speech is usually executed by an elderly (contemporary) Indian character or a historical figure of some social importance. For example, when Pocahontas's father, Chief Powhatan (voiced by Russell Means), speaks in the Disney film Pocahontas (1995), his style is slow, careful, and articulate, eloquent in both conversation and speech making. Consider the following two excerpts (the length of time in seconds is provided in brackets at the end of each utterance, and the rate of articulation tabulated dividing the number of words in each utterance by the length of time) (Gabriel et al. 2000 [1995]):

In this example, both individuals' rates of articulation are fairly similar. Chief Powhatan's pacing for lines 1 and 2 has a rate of 1.75 and 1.6, respectively.When in dialogue with Kekata, shown in lines 3, 4 and 5, the rates of articulation are fairly comparable: 2.5, 2.6, and 2.5, respectively. In the next example, a difference emerges between the speaking rates of Chief Powhatan and Pocahontas (Gabriel et al. 2000 [1995]).

Taken in pairs, the rates for lines 1 and 2 are 3.5 and 2.7; for lines 3 and 4, 3 and 2.3; for lines 5 and 6, 4 and 3; and for lines 7 and 8, 4 and 2.3. In each pair, the rate of articulation for Pocahontas is approximately 1 word per second faster than that for Chief Powhatan. These differences in the rates of articulation across these characters suggest that there is a correspondence between the pacing of dialogue and the character's (and possibly the actor's) age. This pattern links oratory with aging and elders, depicting it as a practice associated with old age, authority, and past knowledge. By contrast, the younger Indian characters appear to have not yet acquired either the style of speech or the social right to perform it. Interestingly, the fact that this style of oratory is performed primarily, if not exclusively, by elderly Indian characters parallels the heritage language distribution of many Native communities. Most remaining speakers of indigenous languages are elders, while most young people do not, or cannot, speak their ancestral language at all.

Morphosyntactically, the four grammatical markers used in HIE are lack of tense, deletion (of various grammatical elements), substitution, and lack of contraction. Lack of morphological tense is the most consistent and predominant pattern throughout all the dialogue transcribed and applies only to verb forms (tense may still be indicated adverbially). Deletion affects subject pronouns, determiners, and auxiliary or modal verbs. Substitution affects subject pronouns, replacing them with either a full noun or the corresponding object pronoun. Lack of contraction affects the merging of be or have verbs (non-modal auxiliaries and copulas) with the preceding subject pronouns and the merging of the negation marker, not, with the preceding verb.10

This would probably affect modal auxiliaries as well, predicting that we should not find forms such as I'll or He'd, but only I will and He would (when, of course, the modal is not deleted as in 4c below).

Lack of tense marking is the most prevalent marker. The productivity of this pattern is partially due to the available deletion of the auxiliary or modal verbs. Since auxiliaries or modals are typically inflected for tense and number agreement, the deletion of such an element would result in the deletion of tense marking. Examples of tense modification are given in (4). Next to each example is the probable standard American English version:

All of these examples display verbs without tense marking, which identifies the speech as nonfluent, indexing the speakers' unfamiliarity with English and hence their foreignness. Similarly, these forms also suggest that these characters, who are unfamiliar with English, are in some way linguistically underdeveloped or lacking in grammatical competence. Child language studies have shown that children often omit tense or any other morphological marking in early speech production, with mastery of this emerging later in their development (Brown 1973; see also Bloom 1972). The use of such a simplified tense system by an Indian character would then open the door for an interpretation of the character as being childlike as well as foreign.

A lack of tense in HIE forms could also be an allusion to differences in the grammaticization and conceptualization of time between Native American languages (and peoples) and standard European languages (and peoples). The popularized yet distorted version of this difference is that many Native Americans are not able to understand the Western concept of time because their linguistically structured perceptions of time are different. Therefore, Native people are often late to appointments and so forth because they're on “Indian time.” This then suggests that they would exclude tense marking from their English utterances because of their lack of understanding of how time is marked in “civilized” modern spheres. However, omission of tense marking doesn't just represent Indians as childlike; it can also be a means to represent their cultural difference as one of timelessness or primitiveness, as nonmodern.11

This practice of representing non-European peoples as timeless has been well discussed in both the anthropological literature (see Asad 1973; Fabian 1983, 1986; Rafael 1992; Raheja 1996; Wolf 1982) and Native American studies (see Bataille 2001; Berkhofer 1978, 1988; Churchill 1998; King 1998; Nason 2000).

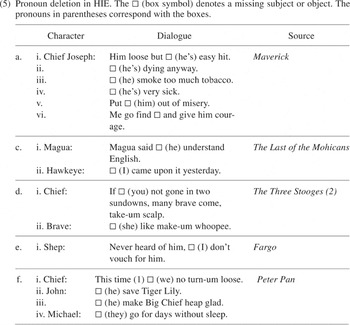

The second pattern is deletion. Subject pronouns, object pronouns, auxiliary verbs, and noun determiners delete. These patterns, however, are not as consistent as the tense-marking pattern illustrated above. The inconsistency of pronoun deletion may be due in part to the fact that whenever the subject (or object) is unclear, a referent is needed. In the cases where the referent can be inferred, we would predict deletion. In much of the dialogue this generalization holds. Consider the following examples:

As these examples illustrate, pronouns can be removed, especially when they can be inferred from the context of the conversation. Another element that can undergo deletion is the determiner (and/or the English plural morpheme, when no determiner is required). Some examples of this are given in (6):

The final case of deletion is the deletion of the auxiliary verb. This pattern appears quite frequently across the samples of dialogue:

This is similar to the pattern noted by Ferguson (1996 [1971]) in his discussion of how copula deletion can be used to mark “foreigner talk” and “baby talk.” Note that auxiliary deletion is also linked with the tense-marking pattern. If the auxiliary is deleted, then no tense will be marked. Overall, the deletion of these linguistic elements presents Native American speech as ungrammatical and/or substandard, and the speakers as incompetent and unable to use SAE “correctly.” Depending on the context of the performance, this incompetence can be accounted for in several ways, such as in relation to a character's limited cognitive abilities or unfamiliarity with English.

The third morphosyntactic pattern is substitution. In these cases, the subject pronoun is replaced by either an object pronoun or a full noun. This pattern is not as prevalent as those above, but it appears frequently enough to provide the following examples12

Interestingly, all of these examples come from productions first released before 1960. This pattern is also noted in the early AI(P)E descriptions from Leechman & Hall 1955 and Miller 1967.

In all of these cases, the subject pronoun is replaced with the object pronoun. Again, this is a common pattern found in both foreigner talk and baby talk, as well as being a salient construction in actual early child language. One potential conceptualization that this pattern can trigger is the image of the Indian speaker as essentially incapable of acquiring the correct pronominal pattern for AE, resulting in a childlike, foreign style of speech that overgeneralizes the object pronoun.

The final morphosyntactic pattern appearing across all the HIE representations is the lack of contraction. In this case, neither the auxiliary verb nor the negation marker merges with the preceding elements, as is common in SAE. In the data, there are only four representations of Indian speech that do not conform to this pattern. All other representations have no contracted elements. Display (9) presents cases of non-contraction where one could expect contraction in SAE speech. Note also that this feature lengthens and slows the utterance, thereby contributing to the ponderous speech style mostly achieved through prosodic modifications13

In a children's program I watched with my daughter recently, a character, whose first language was said to be Polish, visited and spoke in a very slow style with no contractions, perhaps indirectly indexing her foreignness.

The pattern, then, is that there is no contracting of the auxiliary or merging of the negation marker with the auxiliary verb (when an auxiliary is present). For HIE in general, the auxiliary verb is either represented in its entirety (not contracted), or it undergoes deletion. Unlike the earlier patterns that could be interpreted as foreign-sounding or childlike, this pattern more readily lends itself to an image of archaic eloquence (similar to a popularized Shakespearean form of English that does not use contractions; see Montgomery 1998). To reflect a historical setting or sentiment, or to locate their characters in the past, performers can rely on this grammatical feature. Whether individual actors intentionally use this feature or not, the actual preponderance of no contraction across performances neatly corresponds with the historical essence of Indian imagery.

All of these morphosyntactic patterns are variations on standard AE patterns. They form a template from which different styles of speech can be developed, styles that are markedly different from a supposedly standard, and “white,” style of speech. For Indian characters, this style of speech underscores dimensions of foreignness that have been used to represent Indianness as Other (Berkhofer 1988:528). HIE, like most other Indian representations (Berkhofer 1978), is imagined in juxtaposition to some kind of Standard American English (most likely the speech variety of the author, performer, and audience). Within this fictional world, the ungrammatical forms of HIE stand out (as do their dark-toned “proximate” speakers; see Chafe 1993, Du Bois 1986) against the ever-present rumble of grammatical SAE utterances (and their light-toned “proximate” yet “prime” speakers). Remaining is the question of how this deficient style becomes marked as HIE and not some other racialized style of speech.

The most obvious answer is context. But for HIE, there is also another source: certain specialized vocabulary words and lexical imagery used in the dialogue of Indian characters, some of which are taken from actual American Indian languages and historical speeches. These words and phrases, as indexes of Indianness, mark a character's speech as HIE. Besides “chief,” several other terms are common to the dialogue of Indian characters in these television shows and films.

While some of these terms derive from Native American languages (“squaw,” “tepee”; see below), other terms appear first in early American literature. Cutler (1994:132) traces the phrase “happy hunting ground” to James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving. He also credits Irving, along with Mark Twain, for the introduction of “heap” and its association with Indian speech. As for the word “brave,” Cutler (1994:131, 255), citing Mathews 1951, attributes this term to Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. And finally, the expression “paleface” “may be a white coinage,” one of its earliest citations being G. A. McCall's Letters from the Frontier in 1822 (Cutler 1994:132).

Additionally, we see that a particular type of phrase construction is characteristic of, though not exclusive to, HIE. Here I am referring to forms that parallel the syntactic structure of Romance language noun phrases. As Miller (1967:144) notes, Indians were frequently depicted as speaking “in fluent and … courtly English.” This is achieved by exploiting English's flexible syntax. Consider the French phrase les esprits de la montagne. English offers two possibilities for a corollary: “the spirits of the mountain” and “the mountain's spirits.” A more formal sense is attributed to the construction that parallels the Continental pattern. This is due to the long historical interconnections between English and French nobility and the complex sociolinguistic associations that resulted (see Baugh & Cable 1978). What this means for an Indian character is multivalent. As with rate of articulation, the more formal phrase construction in HIE can either be considered dysfluent, and therefore indexical of incompetence, or it can work to index nobility (and the noble savage; see below). Lines b.i, c.i–iv, and d.iii below all exemplify parallelism with Romance possessive phrases, framing the speech as “noble”:

To complete the noble savage motif, we need only add the element of nature, of the primeval (precivilized, hence savage by default). This is provided by figurative language employing nature metaphors. For instance, Indian characters typically portray time through reference to heavenly bodies (“for many moons,” “in two sun downs”), or allude to timeless epochs like “before the white man,” which underscores the image of American Indians as existing in some nonmodern, primitive state before contact with Indo-Europeans14

Again this reference to time along with its implicit conceptualization suggests that time began when we Indians first encountered white people. Before that, we were unaware of time, like children and animals. The white man taught us how to measure and keep track of time.

The example below illustrates contextually how “courtly” speech, marked by the use of French-like noun phrases, pauses, and noncontracted forms, can evoke the “noble savage” image. In this episode of MacGyver, entitled “Trail of Tears,” a Lakota tribe is trying to keep power lines from being strung through a sacred area on their reservation. The Indian character, Mr. White Cloud, has just represented the tribe in the court proceedings and lost the case. He is in the bathroom as the scene opens, splashing water on his face. As he dries his face and raises his head from the sink, an older man with a feather in his long, graying hair appears behind him. This older man is wearing a flannel shirt and a pendant of leather and shell, in contrast to Mr. White Cloud's suit and neat ponytail. The two men begin by exchanging greetings:

In this scene alone, several themes are juxtaposed through the bodies and expressions of these two characters: traditional versus modern, old versus young, religious versus secular, Indian versus white. Linguistically, these contrasts are encoded in the styles of speech deployed by these two performers. Mr. White Cloud, the younger, modern character, speaks a standard variety of English. He uses contractions (lines 12, 17), his cadence is not remarkable (no lengthened pauses), and he speaks plainly, without metaphorical flourishes. Mr. Standing Wolf, on the other hand, has no contractions in his speech (cf. lines 4, 6, 9, 16, 18), his cadence is sprinkled with pauses (lines 2, 6, 9, 10), and he has a flair for metaphorical and adage-like statements (lines 6–7, 9, 10–11). Lines 9–11 also illustrate the way in which the formal possessive phrases lengthen the overall contour of his utterance and produce a more oratorical, formal style in contradistinction to Mr. White Cloud's colloquialisms (lines 5, 8). As this example shows, figurative expressions are another way in which the linguistic image of HIE emerges distinct from some standard AE variety, fluidly absorbed into an eloquent style of speech that can easily find correspondence with the noble savage image. The continued use of these expressions in contemporary representations of American Indian speech reinvests current Indian imagery with the same primeval essence of past representations.

Along with movies and television, this HIE style can also be found in written form, for example in greeting cards. One humorous Thanksgiving card shows a Pilgrim squatting in some bushes while an Indian asks “Why you make poo-poo in poison ivy?” Aside from being a rather odd Thanksgiving greeting, this card plays on a number of features analyzed above.15

This card also portrays white men as ignorant of basic facts of nature.

This is true of Mock Spanish representations in greeting cards as well (see Hill 1995).

The greeting card examples differ from those found in the movie and television dialogues by conspicuously linking negative, demeaning imagery with Indian characters.17

For naturally occurring speech styles with similar modified grammatical components see Philps 1991, Ferguson 1983.

FROM REAL LIFE TO HOLLYWOOD: COMPARING AIE WITH HIE

The first grammatical descriptions of American Indian English and American Indian Pidgin English used as their data depictions of American Indian speech found in romanticized travelogues and works of fiction written between 1823 and 1955 (Craig 1991, Leechman & Hall 1955, Miller 1967). The data were not elicited utterances from actual speakers. To justify these fictional representations as “authentic,” one researcher noted that “language structure cannot be manufactured at the whim of the author” (Miller 1967:144). Whether this is true or not, what is most appealing about these grammatical descriptions is that some of the elements they describe are still found in the speech of today's Hollywood Indians.

Craig (1991:39) identifies a number of American Indian (Pidgin) English linguistic features found in these written sources. Four of her features correspond with HIE features noted above. These similarities are shown in (14):

Though this is unsurprising, there are several differences between Craig's AI(P)E grammar and HIE. First, Craig includes a phonological description (though recall that she is extracting her phonological patterns from written texts) including sound patterns that are not found in film and television performances. Second, missing from the list in (14) is the lack of contraction found in HIE. Third, film and television forms include the third person object pronoun as a replacement for the subject pronoun (14a), perhaps generalizing beyond the initial first person pronominal pattern. Fourth, pause length is not mentioned, though potentially representable in written form as a series of periods between words or phrases. Finally, the analyses by Craig 1991, Leechman & Hall 1955, and Miller 1967 again identify grammatical features based on nonnative speaker representations of American Indian speech, suggesting perhaps that the linguistic forms initially used to identify its grammatical structure were more imagined than real.

In recent decades linguists have begun documenting many of the varieties of English spoken by American Indians. They have shown that different American Indian communities use different English dialects (Bartelt 1991, 2001; Bartelt et al. 1982; Craig 1991; Leap 1993, 1976; Penfield 1976). The language structures of these varieties are patterned and complex varieties of English; they are acquired grammatical systems. They conform to linguistic universal structures and also display influences from each particular community's ancestral language (Leap 1993). This means that AIE varieties are distinct from one community to another; there is no homogeneous AIE language that all American Indians speak.

By contrast, HIE is neither systematically heterogeneous nor acquired. It is neither a dialect nor a language. However, at first glance, HIE does appear to bear some resemblance to real AIE varieties. For example, some varieties have pronoun deletion. Consider the case of Ute English as described by Leap 1993. Leap notes that “subject pronouns are by far the most frequently deleted items within this category, while object pronouns are almost never deleted.” To explain the pronoun deletion pattern found in Ute English, Leap posits three constraints, all relating to auxiliary verb marking and auxiliary verb deletion, and notes that “Ute English speakers use pronoun deletion only after … (these) constraints have been satisfied” (1993:61). For Ute English, the pronoun must be before an AUX-main verb sequence, the AUX must serve an aspectual function, and the AUX must be able to contract or delete. In (5) above (repeated below as (5′)), there are four instances of subject pronoun deletion and two examples of object pronoun deletion. The HIE forms in (5′) do not conform to these constraints, with the exception of line 2, (he) (is) dying anyway.

In (5′) it appears that any pronoun can undergo deletion at any time. In line 2, the pronoun deletes along with the auxiliary verb; in line 3, only the subject pronoun is deleted; in line 4, the subject pronoun and copula are deleted, and in line 5, either the phrase is a command (‘Put [him] out of misery’) with only the object deleted or both the subject (either ‘you’ or ‘we’) and object pronouns (‘him’) are omitted. To account for the deletion pattern, the rule might be: Delete any pronoun when the referent is the same as in the preceding phrase. Generally speaking, contextual inference can account for the HIE pattern. Unlike Ute English, the HIE account is extremely general and constrained not by underlying grammatical phenomena but by the processing of information at a discourse level. What about other varieties of AIE?

Another variety of AIE discussed by Leap has pronoun deletion but patterns according to different grammatical constraints. Mohave English pronoun deletion is constrained by case-marking, in contrast to Ute English pronoun deletion, which is constrained by the auxiliary (Leap 1993:60–62). Again, the deletion is grammatical and not discursive. The overgeneralized deletion of pronouns in HIE means that the application of deletion is at the surface; it is not a grammatically governed phenomenon like those found in AIE. Since the use of deletion in HIE is discursive, whereas pronoun deletion in AIE varieties is grammatical, HIE pronoun deletion is not the result of a direct borrowing from any spoken variety of American Indian English known today.

Although I do not have space to show this here, I would posit that the other grammatical elements of HIE are only allusive to, and not borrowed from, real varieties. The borrowed elements are lexical. A few token words and phrases have been borrowed from specific American Indian heritage languages and documented American Indian oratory. Berkhofer (1978:88) and Marsden & Nachbar (1988:608) both point out the role of treaties in the emergence of an American Indian drama and rhetoric. Berkhofer (1978:88) in particular notes that “early American men of letters” described

their (Indians') language … (as) filled with picturesque allusion and metaphor and their legends equaled the tales of Old World folk,” [and that] “Indian rhetoric … existed as a kind of literature in the form of treaty proceedings … (to the point where) Jefferson's version of Logan's famed speech was memorized … by schoolchildren of the nineteenth century.

Similarly, Edna Sorber examines several non-Indian descriptions of American Indian oratory, including Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's (see also Bauman 1995, Bauman & Briggs 2003), and points to the authors' use of evaluative terms such as “beautiful metaphors and rich imagery” and “polished orators” (Sorber 1972:232). She also identifies this expressive tradition as a means through which the image of the noble savage was and is maintained. This is in contrast to the ignoble savage, who is either silent or reduced to grunting. Sorber also argues that the fictional depiction of American Indian oratory as eloquent transported the image of the noble savage into the twentieth century.

Along with picturesque and metaphorical phrasing as an index of Indian speech (and now HIE), several Indian heritage language terms have been adopted into the English language and recycled as signs for denoting Indian speech. Some examples from (9) above are the following, along with their etymological origins:

In unimaginative attempts to distinguish an Indian character's speech from non-Indian characters' speech, authors have incorporated Indian-related or American Indian heritage language words into their characters' speech. Words such as these, which have been borrowed from American Indian languages and incorporated into mainstream American English, can be readily identified and reduced to indexes of Indianness. Given these linguistic modifications, the next section examines the ways in which these linguistic features articulate with other meaningful dimensions and become racialized.

HIE SPEECH AND THE “WHITE MAN'S INDIAN”

As discussed above, a number of grammatical features that appear in HIE, such as verb deletion, object pronoun substitutions for subject pronouns, and a limited lexicon, also appear in other imagined linguistic representations and stylized, caricature-defining ways of speaking (Ferguson 1996; Hill 1993a, 1993b, 1995; see also Lippi-Green 1997).18

This movie is based on a “subversive” comedy-western television series that aired from 1957 to 1962, starring James Garner as Bret Maverick, a wisecracking gambler, and Jack Kelly as his brother Bart. It was created by Roy Huggins, who attempted to parody other television westerns at the time (http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/M/htmlM/maverick/maverick.htm). The movie itself continues in this vein, with Chief Joseph as a parody of the “traditional” Indian character in Hollywood westerns (an Indian actor “playing Indian”).

Part of this linguistic imagery corresponds with “playing Indian” (Deloria 1998; Green 1988a, 1988b), a practice of non-Indians in which they dress up or masquerade as Indians. Examples of this range from the Boston Tea Party to contemporary boys' and girls' clubs like Indian Princesses and Indian Guides, and the phenomenon known as “Indian hobbyism” (Powers 1988, Taylor 1988). In boutique toy catalogs, parents continue to be encouraged to purchase Indian outfits and tepees for their children. In films as well, moments of playing Indian emerge. It is at these moments, when characters are playing Indian, that the most elaborate performances of HIE are found. This linguistic image indexes features equated with both the noble and the not-so-noble savage.

To illustrate the process through which language (HIE) facilitates or contributes to the image of Indians as other, I will examine two scenes from different movies, one contrasting foreigner talk with HIE, and the other, children's talk with HIE. The goal is twofold: to show how HIE differs from other stylized forms of fictional speech, and to show how HIE articulates with various imagined Indian characteristics. The first example comes from the movie Maverick (1994).19

However, in Chief Joseph's interaction with Bret Maverick (played by Mel Gibson), Graham Green's character speaks a standard American English variety, as does Gibson's character.

Note that Chief Joseph begins by speaking French to the Russian trader, then shifts to HIE – not AE – when his use of French doesn't align with the trader's expectations.20

This Disney movie is adapted from James A. Barrie's children's story Peter Pan. The story was first produced for the stage in 1904, eventually appearing as a children's book in 1911. Its various other reincarnations, including Disney's, were as a play with music (1950), as a musical comedy (1954, revived in 1979) that was also performed on television, as a silent film (1924) and as a feature-length animated cartoon (1952).

The differences between the speech styles of the two characters in Maverick are lexical and grammatical. Lexically, the Russian trader only uses two specialized terms, and each only once: noble savage (line 4) and injun (line 13). Chief Joseph, however, uses a variety of marked expressions: How (once, line 3), white man (twice, line 3 and later), injun (four times, as in line 12), wampum (line 16), and happy hunting ground (later in the scene). Furthermore, while both characters are multilingual, Chief Joseph's English speech is littered with different types of deletion: pronominal, verbal, and determiner (lines 8, 16, 22–24, 26, and later), all grammatical elements of HIE. The Russian trader's speech has only one example of deletion (line 11), What is (the) greatest Western thrill?, produced when exactly repeating the phrase uttered by Chief Joseph (line 8). The greater number of specialized terms and the use of deletion in Chief Joseph's speech produce a less fluent style of English, indexing his position as savage, in keeping with the Russian's expectations (recall that Chief Joseph is playing Indian here).

The second example comes from Disney's Peter Pan, released in 1952.21 The story is about three children (Wendy, John, and Michael Darling) from a middle-class English family living in London who revel in the adventures of Peter Pan. In scene (16) below, John and Michael, after having flown with Peter Pan, Tinkerbell, and Wendy to Neverland, are caught and bound by the Indians along with the other Lost Boys. From the text, we understand that this is usually a routine form of play. However, this time the Indians aren't playing because Tiger Lily, the “Indian Princess,” is missing and the Lost Boys now stand accused. The boys are tied to a pole with firewood beneath them in the middle of an encampment of tepees (Luske et al. 2002 [1952]).

The Indian Chief in this animated movie resembles a heavy Chief Wahoo (mascot of the Cleveland Indians) with a giant proboscis, a stout physique, and scarlet skin tones. He sports a feathered headdress, black hair, and leather buckskins. His voice is deep and gravelly and his pace slow, ending with a very slow, and low, burn-um at stake. His style of speech is both paragon and parody of Hollywood Injun English.

Several HIE elements filter through the Chief's speech. First, the lack of tense and aspectual marking on verbs is pervasive (lines 7, 17, 19, 20, 27). Second, several grammatical forms are deleted, from auxiliary verbs to pronouns (lines 17, 19, 20, 27). There is also one example of pronoun substitution, me replacing I (line 19), and several HIE-indexical lexical items, including liberal use of -um (lines 5, 7, 17, 19, 26, 27). Additionally, contractions are missing from the Chief's pronouncements (one exception to this is the song “What makes the red man red?” sung by the Indians and the Chief). In contrast, the Lost Boys' speech has contractions (lines 16.1–4, 22), as does the speech of the Darling children (lines 16.1, 23; 17.1–3, 7) (Luske et al. 2002 [1952]).

The foreignness of style is further emphasized when John switches from speaking his standard English variety to an HIE style when translating the Chief's signed oration (lines 4–6). Included in the translation is an extensive use of pauses, omission of morphology (no tense marked on save or make), deletion of verb copula (line 4; see also the Chief's line 9) and subject pronouns (lines 5, 6), and the appearance of the specialized term heap (line 6; see also 7). Of equal interest is the fact that John is able to translate this signed oration, suggesting that this mode of communication is more primordial than spoken language. The Chief never switches styles (spoken or signed) in relation to his interlocutor; he only speaks HIE. The one other Indian character who speaks also only uses HIE, doing so when addressing Wendy (Squaw get-um firewood). While the English-speaking children are able to switch styles, and some are even able to understand new codes, the Indian characters do not participate in this linguistic precocity. This might be because of their age/status differences, but, given the remedial and primordial nature of their linguistic styles, it is more likely indexical of some cognitive difference, suggesting on the one hand that these adult Indians are even less sophisticated and developed than European children, and on the other that they cannot shift codes because their speech emanates from their essential nature as Indians.

The excerpts from these two movies also exemplify the connection between speaking HIE and playing Indian. In Peter Pan, the Lost Boys only use HIE in two of their interactions with the Chief, the greeting, How! and the expression ugh. John, Michael, Peter Pan, and Wendy, on the other hand, switch between speaking HIE and their standard English styles more frequently, when interacting with the Indian characters, translating (see ex. 16), and playing Indian. When Wendy responds to an Indian character's directive to get firewood, she uses HIE, saying Squaw no get-um firewood. Squaw go home. While dancing around the Indian encampment, Michael says Squaw take-um papoose, directing Wendy to hold his teddy bear. Also, upon returning to the Lost Boys' hideout and still in Indian character, Peter Pan tells Wendy, Michael, and John, No go home, stay many moons, have heap big time. In these cases, HIE serves as a second-degree index of their pretend identities as Indians.

In Maverick, Chief Joseph's playing Indian is clearly marked by his switch to HIE. A similar observation can be made about the “Princess Running Mouth” greeting card above. The use of HIE becomes licit (and more frequent) when characters are playing Indian, and it reifies the sociocultural differences being assumed by these representations. Thus, HIE, along with other fictional pidgin-like ways of speaking, encodes social difference, manufacturing and accentuating cultural divides through the use of contrastive speech styles in popular media. However, unlike “foreigner talk,” “baby talk” and Mock Spanish, HIE has a historical dimension that emerges as part of and continues to reproduce the timeless, primordial dimension of American Indian representations. Even contemporary films, such as The Indian in the Cupboard (see Strong 1996, 1998 for a critical analysis), explicitly represent their Indian characters in a historicized fashion. This perpetuates the ever-present popular fiction that Native peoples for the most part have vanished, that there is no longer any person or group that is “authentically” Indian, but only those that “play Indian.” By creating a style of speech that is markedly different from some standard variety of spoken English, mapping this style onto an Indian character, and then locating this character in the past, writers transform the modern American Indian into a historical mirage. Paradoxically, the overall linguistic image itself is ahistorical, or timeless, since HIE never existed as a real language, dialect, or way of speaking. Rather than maintaining historical accuracy, then, this linguistic image accentuates the foreignness of Indian characters, serving as both index and icon of the conventionalized characteristics associated with American Indians.

While the aberrant grammatical elements of HIE become suffused with indexical significance through their association with the racialized, and often pejorative, images of American Indians, these elements also contribute to the racialization of these images by underscoring certain characteristics of which language is assumed to be indexical (intelligence, stages of development, ethnicity, foreignness, social difference). Several “degrees of indexicality,” to borrow Michael Silverstein's phrase (2003), are at play here. For example, the Chief's slow, ponderous delivery is a first-degree index of oratorical style, which then is a secondary index of this character's specialized (elevated) social position. However, because the Chief speaks in the aberrant HIE style, a first-degree index of difference, his style of speech becomes a second-degree index of foreignness as savagery, as suggested by his clothing and “barbaric” practices. In conjunction, these indexical links have a third degree of referentiality evoking the “noble savage” image. In this semiotic way, these linguistic images become racialized and racializing aspects of representation that contribute to the reproduction and transformation of ideologies about languages and peoples.

HOLLYWOOD INJUN ENGLISH, RACISM AND THE OBJECTIFICATION OF NATIVE AMERICANS

Most studies elucidating these covert racist images have focused on how individuals discursively represent different minority groups (van Dijk 1993, 1996; Caldas-Coulthard & Coulthard 1996) or how these representations emerge and are then used in public arenas, in white public spaces such as newspapers, literature, and television (for examples see Morrison 1992 for representations of African Americans; Cassuto 1997 for representations of African Americans and Native Americans; Butler 1997 for representations of African Americans and women; Quiroga 1997; Urciuoli 1998; 2003 for representations of Hispanic Americans; Chun 2004, Palumbo 1994 for representations of Asian Americans). For Indian imagery, such research has often critically analyzed these representations in relation to the development of U.S. nationalism. Predictably, the conventionalized imagery depicts Indians as wild, savage, heathen, silent, noble, childlike, uncivilized, premodern, immature, ignorant, bloodthirsty, and historical or timeless, all in juxtaposition to the white civilized, mature, modern, (usually) Christian American man. According to Stern & Stern 1993, the two portrayals of Native Americans that most often entertain us at the movies are the “faceless savage on horseback … pursuing white people for no other reason than an insatiable lust for scalps … [and the] noble culture that embodies nature's harmony and is victimized by settlement” (47–48). Whether fiend or victim, much of the imagery has presented American Indians as unsocialized (childlike) and uncivilized (alien).

This essay in turn has drawn on these critical studies, but it directs our focus toward linguistic images. I have examined here the template of grammatical features used to denote Native American speech and how these generic linguistic features link with overt pejorative representations (commodified and fetishized aspects of Indianness) as characters display, perform, or play Indian. In short, to inhabit an Indian identity, you only need to declare “How!”

One of the most enlightening studies to date on the indexical construction of racism in Standard AE is Hill's work on Mock Spanish (Hill 1993a, 1993b, 1995, 1998). She argues that Mock Spanish is an example of the dominant group's “incorporation” or expropriation of a desirable resource (language) from a subordinate group (Spanish-speaking minorities). Through incorporation, Mock Spanish becomes a site for racializing the groups that speak Spanish. This is achieved indirectly through the distortion of Spanish pronunciation and the association of Spanish expressions with negative images. That is, humorous and pejorative representations of Spanish indirectly index negative images that members of the dominant group associate with Spanish-speaking populations. This results in the perpetuation of a conceptual lowering of the status of Spanish and its speakers.

This covert conceptual subordination is the factor that maintains racism. However, in the case here, it is not the actual native or heritage language of a group that is the target of expropriation, denigration, and mockery (with lexical exceptions); the target is ideologically more distant and detached from the actual community of speakers than in the case of Mock Spanish. That is, representations of Native American speech are based on authors' imagined realities, reflective of ideological assumptions, and not on everyday interaction.

One of the ways in which these images are evoked and reproduced is through what I have called HIE, a simplified, “corrupted” form of English composed of “disorders of language” (Hill 1995) that iconically represents Native American speech. Through this iconicization, HIE fluidly indexes various perduring, naturalized characteristics historically linked to the images of American Indians. HIE forms contribute to and strengthen the saliency and accessibility of these cartoonish and nostalgic (romantic) Indian images, a U.S. imaginary of Indianness and the continued domination or disempowerment of American Indians. By speaking Hollywood Injun English (when pretending to be Indian), the performer does not mock any American Indian language, but rather imbues his Indian character with a weak mind and a childlike persona, and locates this character as subordinate to a dominant white public.

Furthermore, representing the speech of Native Americans as substandard and foreign portrays Native American speakers as foreign, as not native. This need to imagine Native Americans as outside the national boundary, as not native but foreign, has been crucial to the development of the U.S. nation and manufacture of a national U.S. identity. As Deloria 1998 has pointed out, this continual dialectic between the inclusion and exclusion of a Native American Other, a practice integral to the ideological construction of a U.S. nationhood, or “national subjectivity” (Rosenberg, cited in Deloria 1998:7; see also Strong & Van Winkle 1993), is present throughout historical U.S. nation-building narratives and appears over and over in films, books, cartoons, and so forth, where non-Indians (and Indians) are playing Indian, performing Indianness in dress and in speech. Interestingly with regard to speech, Indian characters have a voice only when they are either from the past, remembering the past, or situated in the past. The archaic linguistic forms reinforce this chronology, this historicized placement.

Part of this dialectic, then, animates the Indian character or role, but only in historic contexts. The other half of the dialectic dis-animates or silences the same character. Given that the U.S. nation has a distinctive monolingual, Standard American English bias that equates a particular variety of the English language with nationality (Milroy 2000:82; Silverstein 1996; see also Lippi-Green 1997; Silverstein 2000), the practice of representing American Indian speech as nonstandard or foreign further silences the already vanishing Indian in an attempt to extinguish him once and for all from a national landscape that has historically and economically lauded an American Indian presence for its own self-promotion and consumption. The fact that linguistic representations further instantiate this dialectic is not surprising, then. In fact, they can be more effective than other mediations by virtue of their being more subliminal, more covert.

Finally, particular language features, often described as “accents” or as “incorrect” and “ungrammatical” utterances, easily become indexical markers for invoking a particular ideology, theme, or cognitive model (Holland & Quinn 1987, Irvine & Gal 2000, Lippi-Green 1997). It is in this way that language in all of its subconscious, habitual, unreflective glory can be a prime site for the perpetuation of negative, racist and racializing sentiments – even when people intend to act otherwise. When American Indians are assigned dialogue in an unconventional, inarticulate form of English, they continue to be intellectually and economically marginalized in the imagination of public viewers.

In sum, I have shown that popular depictions of Native American speech in white public space are covertly racist. I have shown how the structure of AE has been modified in order to depict a fictional Hollywood Injun English form. I have discussed the ways in which these forms deviate from actual American Indian English varieties, but share some features with historical descriptions of American Indian Pidgin English. I then argued that this “abnormal” linguistic style is an iconic representation of real-life American Indian speech that indexes an image of Indians as foreign victims, eloquent yet unsocialized. Additionally, these linguistic images perpetuate the historical placement of Native Americans as characters who exist only in a national past and not in a modern present. While an Indian presence is acknowledged in a reconstructed U.S. history and commodified in everyday tourist attractions, as contemporaries American Indians continue to be imagined outside this national landscape, linguistically and otherwise.

The next step is to explore how and to what extent the ideologies indexed by these representations are acquired. Given that people are socialized into and through language (Ochs 1990; Schieffelin & Ochs 1986a, 1986b; Garrett & Baquedano-López 2002), and through socialization learn to equate certain styles of speech with particular situations, events, and/or actors, it seems reasonable to assume that people as culture consumers will understand new experiences in relation to the ways in which they have been socialized. In relation to this study, what is most interesting about language socialization is the ways in which consumers in white public space are socialized into mapping particular linguistic features onto representations of difference, subtly reinforcing or transforming the representation. Here HIE speech not only indexes a character's Indianness (and nonwhiteness) but can also manipulate the representational force of an image, from that of an eloquent enemy to that of an incompetent foreigner.

APPENDIX

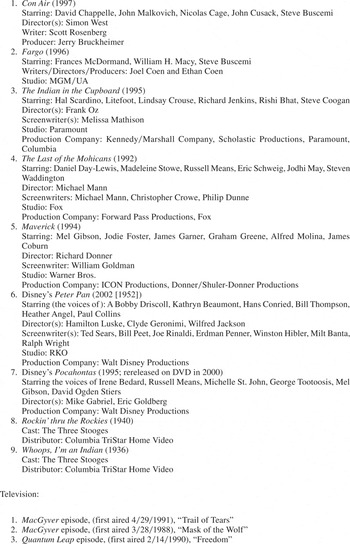

List of films and television shows used in the analysis

References

REFERENCES

- 97

- Cited by