Among the many musical novelties that Italian audiences could admire around 1730, as the galant style spread quickly up the peninsula, was a passage that recurs several times in ‘Pallido il sole’, an aria in Johann Adolf Hasse's Artaserse (Venice, 1730; Example 1). A father, distraught because his son is about to be put to death for a crime that he (the father) committed, expresses his anguish in a melody that rises from scale degree 1 up to 5, while the bass descends chromatically from 1 down to 5 (through what Peter Williams has called the ‘chromatic fourth’Footnote 1). The passage reaches its climax on the word morte (death) as the two diverging lines reach an octave on the fifth scale degree by way of an augmented-sixth interval – ‘the most modern harmonic ploy in [Hasse’s] arsenal’, in the words of Daniel Heartz, who continues: ‘To make it more thrilling he repeats it directly, forte.’ Footnote 2 Hasse's choice of this music for the aria's opening words gave him the opportunity to use it four times in the A section alone (twice that, counting the da capo repeat). It truly dominates the aria: a musical obsession that powerfully expresses a father's anguish.

Example 1 Johann Adolf Hasse, Artaserse (Venice, 1730), ‘Pallido il sole’, bars 13–19. Translation: ‘The sun is pale, the sky is dark, pain threatens, death approaches: everything fills me with remorse and horror.’ (The Favourite Songs in the Opera Call’d Artaxerxes by Sig.r Hasse (London: John Walsh, c1735))

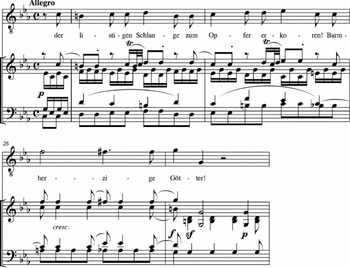

Sixty-one years after Hasse wrote ‘Pallido il sole’, Mozart depicted a young prince being pursued by a monstrous serpent (Example 2). Tamino cries out for help in C minor, and on the words ‘Barmherzige Götter!’ (compassionate gods) his voice ascends to the fifth scale degree while the bass descends chromatically from tonic C to dominant G. The vocal line and bass reach the octave by way of a climactic augmented sixth (A♭ in the bass, F♯ in the voice).

Example 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, Introduction, bars 24–27. Translation: ‘the chosen victim of the crafty serpent! Compassionate gods!’ (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 2, volume 5/19, ed. Gernot Gruber and Alfred Orel (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1970)). Used by permission

Mozart was not the only composer in 1791 to associate diverging chromatic lines and the interval of the augmented sixth with violence and mortal danger. So did Joseph Weigl, a student of Salieri and a music director at the court theatres in Vienna, where he had directed rehearsals and performances of Figaro and Don Giovanni. Just a few months before the first performance of Die Zauberflöte, Weigl presented Venere e Adone, a large-scale cantata for four soloists and chorus, at Eszterháza. In the aria ‘Se gli occhi ridenti’ Mars, the god of war, threatens his consort Venus: if she is unfaithful he will bring war and destruction to the world. About two-thirds of the way through this D major aria, D minor intervenes, and Mars sings a rising chromatic line while the accompaniment descends through the chromatic fourth (Example 3).

Example 3 Joseph Weigl, Venere e Adone (Eszterháza, 1791), ‘Se gli occhi ridenti’, bars 111–123. Translation: ‘destruction and war cover the earth’ (based on the autograph score, A-Wn Mus. Hs. 19412, available at <www.onb.ac.at>)

A year later, in London, the Bohemian composer Adalbert Gyrowetz used more or less the same progression as Hasse, Mozart, and Weigl in the first movement of his Symphony E♭-5 (Example 4). But here it serves a different purpose. Inspired by the latest symphonies of Haydn (whom he befriended in London), Gyrowetz sought to lay this movement out on the largest possible scale. In the recapitulation, he set up the return of the second theme in the tonic with a slowly unfolding harmonic progression: first V7– I (bars 224–228), then the passage with chromatically diverging lines (bars 228–232), leading to what Robert O. Gjerdingen might call a Ponte (bars 232–234),Footnote 3 a medial caesura (bar 234), five bars of caesura-fill (bars 234–238),Footnote 4 and then finally the second theme (beginning at bar 239; not shown). The primary purpose of the chromatic progression here is structural: it is a grand half cadence, beginning on the tonic and ending on the dominant. Gyrowetz uses it as a compositional building-block amid other blocks that are equally important in establishing the symphony's structural integrity. The chromatic passage, which we hear only once, is an exciting symphonic event, animated by a series of dramatic tirades (very rapidly rising scales) in the strings alternating with tutti hammerstrokes. But it has little or none of the tragic intensity of the chromatic passages by Hasse, Mozart and Weigl.

Example 4 Adalbert Gyrowetz, Symphony E♭-5 (London, 1792), i, bars 224–238 (based on the facsimile of the autograph score in Adalbert Gyrowetz, 1763–1850: Four Symphonies, ed. John A. Rice (The Symphony 1720–1840, Barry S. Brook, editor-in chief) (New York: Garland, 1983))

The passages by Hasse and Gyrowetz are in the major mode; those by Mozart and Weigl are in the minor. Hasse's ascending line begins on the first scale degree; the ascending lines by Mozart, Weigl and Gyrowetz begin on 3.Footnote 5 Part of Mozart's ascending line (the crucial E♮) is hidden in an inner part; all of Gyrowetz's ascending line is similarly hidden. Hasse's descending chromatic bass includes the leading note, the basses by Mozart, Weigl and Gyrowetz skip the leading note. Despite these differences – the different contexts in which the four composers used these passages, and the different uses to which they put them – it might be useful to think of all four passages as representing a single voice-leading schema analogous to those introduced by Gjerdingen, Vasili Byros, William E. Caplin, W. Dean Sutcliffe and others. In this article I will briefly survey the use of this schema by eighteenth-century musicians, who relied on it not only as an intensely expressive gesture that could effectively enhance the most tragic moments of a work, but also as a compositional building-block: a particularly ornate half cadence that can be described in conventional harmonic terms as an elaboration of the progressions I–V or i–V.

THE LAMENT, THE OMNIBUS, THE CHROMATIC WEDGE, THE PASSACAGLIA PROGRESSION, THE MORTE, THE MONTE

The chromatic passages in Examples 1–4 exemplify the Lament voice-leading schema, as defined very broadly by Caplin. He describes the Lament as ‘characterized by a bass line that descends stepwise from the tonic scale-degree to the dominant, thus spanning an interval of a perfect fourth’. The Lament schema can be either major or minor, diatonic or chromatic; furthermore, ‘no one melodic pattern emerges as a conventional counterpart to this bass line’.Footnote 6

Under the wide conceptual umbrella of Caplin's Lament are some (but not all) of the many progressions in which the treble and the bass diverge chromatically. Referring to these, some musicians use the term ‘omnibus’,Footnote 7 others prefer ‘chromatic wedge’.Footnote 8 For Paula J. Telesco, the omnibus, ‘in its simplest classic form’, is more specifically a progression in which the bass descends through the chromatic fourth from scale degree 1 down to 5 while the treble ascends from 5 to 7 (in minor, raised 7); it ‘prolongs a dominant seventh via a chromatically filled-in voice exchange involving scale degrees ![]() $\hat 5$ and

$\hat 5$ and ![]() $\hat 7$; the resulting progressions are filled with enharmonic double entendres’.Footnote 9 Closely related to such progressions – many of them beyond the purview of this article – is one that Telesco calls the ‘passacaglia progression’, which has the same chromatically descending bass as the omnibus but a treble that ascends from 1 to 5 (Example 5). In this and all the examples that follow (and in the text as well) I have adopted Gjerdingen's use of black disks to identify scale degrees in the treble, and white disks to identify scale degrees in the bass. Telesco's passacaglia progression corresponds to some (but not all) of what Steven Jan, in his study of Mozart's music in G minor, refers to as ‘chromatic tetrachord figures’.Footnote 10

$\hat 7$; the resulting progressions are filled with enharmonic double entendres’.Footnote 9 Closely related to such progressions – many of them beyond the purview of this article – is one that Telesco calls the ‘passacaglia progression’, which has the same chromatically descending bass as the omnibus but a treble that ascends from 1 to 5 (Example 5). In this and all the examples that follow (and in the text as well) I have adopted Gjerdingen's use of black disks to identify scale degrees in the treble, and white disks to identify scale degrees in the bass. Telesco's passacaglia progression corresponds to some (but not all) of what Steven Jan, in his study of Mozart's music in G minor, refers to as ‘chromatic tetrachord figures’.Footnote 10

Example 5 Prototype of the passacaglia progression in C minor, adapted from Paula J. Telesco, ‘Enharmonicism and the Omnibus Progression in Classical-Era Music’, Music Theory Spectrum 20/2 (1998), Example 11 (256)

To facilitate the comparison of examples, I have standardized the numbering of scale degrees as follows (of course this ‘spelling’ of scale degrees often differs from the notation itself):

The passages by Hasse, Mozart, Weigl and Gyrowetz quoted in Examples 1–4, despite their differences, could all be described as chromatic tetrachord figures and as examples of the passacaglia progression. I prefer to refer to the progression with a term that acknowledges its close connections with Italian opera and its associations with sadness, tragedy and death. I avoid ‘Lament’ in deference to Caplin's use of that term for a much broader schema. Following Gjerdingen's adoption of Italian words for some schemata, I propose that we refer to the schema exemplified in the passages quoted in Examples 1–4 (and in Telesco's passacaglia prototype) as the ‘Morte’. With this term, I do not mean to suggest that the Morte is always associated with death, just as Caplin's Lament schema is not always associated with grief. The convenience of a short, memorable and evocative term to refer to all manifestations of the schema will, I hope, outweigh this obvious disadvantage: that it does not apply to every manifestation with equal appropriateness.

The Morte, both its technical procedures and its expressive connotations, had its roots in the seventeenth century.Footnote 11 Ground-bass laments using the descending chromatic tetrachord (what the seventeenth-century theorist Christoph Bernhard called the passus duriusculus) were an obvious precursor. But such laments rarely involved chromaticism in the melody and the bass simultaneously, and most seventeenth-century composers used the augmented-sixth interval sparingly.Footnote 12 Composers of the nineteenth century continued to develop chromatic wedge progressions, extending their range in both directions well beyond the chromatic fourth and enhancing their harmonic complications.Footnote 13 Thus the Morte, as illustrated in Examples 1–4, is largely characteristic of the eighteenth century.

The Morte shares some features with another galant schema that Gjerdingen, following the eighteenth-century theorist Joseph Riepel, has called the Monte. The Monte tonicizes the fourth scale degree and then the fifth scale degree, often by means of a bass that ascends chromatically from ➂ up to ➄.Footnote 14 The Morte can be thought of as a kind of inverted Monte, with the chromatic ascent in the treble, and with the added complications of the descending chromatic bass and the augmented sixth. Both the Monte and Morte often serve as half cadences, their ultimate destination being the local dominant.

How did eighteenth-century musicians themselves refer to the Morte, and how did young musicians learn it? Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818), a student of Francesco Durante and a composition teacher in the Neapolitan conservatories, seems to have been particularly eager to instil in his students an ability to handle bass segments consisting of the descending chromatic fourth. He included them in many of his partimenti.Footnote 15 In his Regole musicali per i principianti di cembalo (Naples, 1775) he prescribed two patterns for realizing such segments. In one, the treble descends in a series of 7–6 suspensions against the bass. In the other, ‘a partimento descending by semitone can be accompanied by contrary motion’ (‘Il partimento discendente di semitono potrà essere accompagnato per moto contrario’).Footnote 16 Fenaroli's subsequent instructions make clear that this second option involved what I call the Morte. He definitely sanctioned its use, and in his partimenti he provided many opportunities for his students to practise it.

Giorgio Sanguinetti, in elucidating Fenaroli's Regole, refers to the 7–6 pattern as the ‘favored accompaniment’ for descending chromatic fourths. In his realization of partimento no. 2 from Fenaroli's book 4, Sanguinetti uses the 7–6 pattern (‘the standard choice’) consistently for the partimento's chromatic descents (Example 6).Footnote 17 But the Morte would be an equally idiomatic choice (Example 7). Best of all might be to use the 7–6 and the Morte in alternation.

Example 6 Fedele Fenaroli, Regole musicali per i principianti di cembalo (Naples, 1775), book 4, No. 2, bars 1–9, as realized in Giorgio Sanguinetti, The Art of Partimento: History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 181

Example 7 The same partimento as in Example 6, but with Sanguinetti's 7–6 realizations of the descending chromatic basses replaced with realizations using contrary motion

Fenaroli's chromatic fourth includes the leading note; but we have seen several chromatic fourths that descend a whole step from ➀ to ♭➆. The presence or absence of the leading note allows us to divide examples of the Morte into two classes, which we might call the ‘six-stage Morte’ (with the leading note in the bass, and with the ascending line in the treble usually starting on ❶) and the ‘five-stage Morte’ (without the leading note in the bass, and with the ascending line in the treble usually starting on ❸ or ♭❸).Footnote 18 Composers used the Morte, like other manifestations of the Lament schema (as defined by Caplin), in many different formal contexts – sometimes at the beginning of a movement or a section of a movement, and sometimes as a continuation or a response.Footnote 19

They tended to use the six-stage Morte at the beginning of movements (as in Examples 1 and 7) and the five-stage Morte immediately after a dominant chord (as in Examples 2, 3 and 4). They may have felt that the presence of the leading note within the preceding dominant chord made sounding it at the beginning of the chromatic descent unnecessary or unpleasing.

The variety of structural roles that the Morte played suggested the idea of organizing this article not chronologically or geographically but according to the formal contexts in which we find the schema being used. I will begin with a few examples of its use in slow introductions, and continue with examples of its use as a movement's principal melodic material (as in Hasse's ‘Pallido il sole’) and in modulatory and connecting passages (as in Gyrowetz's recapitulation). I will conclude by discussing diverging lines that go beyond the fifth scale degree – thus subverting one of the schema's most characteristic conventions.

THE MORTE IN SLOW INTRODUCTIONS

Although slow introductions, in Caplin's words, ‘seem especially suited to the immediate onset of a lament bass’,Footnote 20 the idea of a Morte in a slow tempo at the very beginning of a work seems to have occurred to eighteenth-century musicians most often in connection with sacred music – and secular music with supernatural connotations. In a fast tempo and in a modulatory passage a Morte (especially a five-stage Morte) passes by so quickly that listeners might not perceive it as particularly dark or serious. But presented at the beginning of a work, defining the tonic, and in a tempo slow enough that each step of the diverging lines and especially the climactic augmented-sixth interval can be heard distinctly, the Morte could have communicated darkness and seriousness quite vividly. Indeed, the slow Morte was one of many musical elements that eighteenth-century musicians and listeners associated with death, ghosts and other aspects of the supernatural – devices that, in combination, are sometimes thought of as constituting an ombra topic or an ombra style.Footnote 21 The darkness and seriousness conveyed by the Morte in slow tempo was especially appropriate in music for such solemn rituals as the mass.

Mozart's Mass in C major k317 (‘Coronation Mass’, Salzburg, 1779) is mostly a festive work, but it begins with a splendid slow introduction that seeks to inspire awe and to evoke power, grandeur and mystery. The Morte, used in conjunction with rhythms characteristic of the French overture, was perfect for such a purpose. Mozart seems to promise a six-stage Morte, with diverging lines in the treble and bass (the latter chromatic). But he interrupts its progress in favour of another powerfully expressive schema, what Byros has dubbed the Le-Sol-Fi-Sol (Example 8).Footnote 22

Example 8 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Mass in C major k317 (‘Coronation Mass’), Kyrie, bars 1–5 (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 1, volume 1/Abt. 1/4, ed. Monika Holl (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1989)). Used by permission

Twenty-seven years after the composition of the Coronation Mass, in 1806, Mozart's former student Johann Nepomuk Hummel wrote his Missa Solemnis in C major for the wedding of Princess Leopoldine Esterházy, one of a whole series of masses commissioned by Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II from his Kapellmeister Haydn and from Albrechtsberger, Beethoven (the Mass in C) and others. Hummel begins his C major mass with a majestic slow introduction clearly inspired by that of the Coronation Mass. (The relationship is easy to hear despite Hummel's unorthodox ❸–❹–❸ opening.) Hummel took over Mozart's incipient Morte and allowed it to continue to its climax, almost as if he were correcting his former teacher (Example 9).

Example 9 Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Missa Solemnis in C major (1806), Kyrie, bars 1–4 (based on the full score, ed. Allan Badley (Wellington: Artaria, 2002)). Used by permission

In using a slow Morte in this sacred context, Hummel was building on a long tradition. Already in 1733 Jan Dismas Zelenka, an early and devoted adherent of the augmented-sixth harmony in general and the Morte in particular,Footnote 23 was putting them to stunning use at the beginning of his Officium Defunctorum (zwv47), music for the funeral of Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony. The opening Largo begins with a Morte almost frightening in its intensity (Example 10). Although the ➀–➆–➀ with which this passage begins does not conform to our expectation for a steadily descending bass, the relentless ascent in the treble encourages us to hear the whole passage as a six-stage Morte with an extra tonic chord inserted between stages 2 and 3.

Example 10 Jan Dismas Zelenka, Officium Defunctorum, zwv47 (Dresden, 1733), Invitatorium, bars 1–5 (based on a transcription by Christoph Horrix after the autograph in D-Dl, Mus. 2358-D-46, on behalf of ‘Das Erbe deutscher Musik’, <www.erbedeutschermusik.de> (Depotarbeiten), kindly furnished by Wolfgang Horn). Used by permission

Zelenka's stark Morte pervades the opening movement of his funeral music, returning several times as a kind of leitmotiv. Handel, in contrast, used only one Morte in the chorus ‘Since by man came death’, in part 3 of Messiah (1741), a chorus that juxtaposes two completely different kinds of music to make a theological point. By 1741 Handel had had ample opportunity to hear the effect of the Morte in the music of Hasse and other younger composers. He chose a Morte in A minor to symbolize the fate of mankind before the coming of Christ. Sung a cappella, this Grave depicts the world of the Old Testament (Example 11). The dominant chord with which the Morte ends sets up the Allegro in C major, accompanied by orchestra: a celebration of the resurrection, as recorded in the New Testament, and its promise of eternal life.

Example 11 George Frideric Handel, Messiah (1741), ‘Since by man came death’, bars 1–6 (from the autograph in GB-Lbl, available on the library's website, <www.bl.uk>)

Eighteenth-century opera composers seem to have considered music as sombre as that at the beginning of Handel's chorus inappropriate in the theatre during the carnivalesque celebrations to which operatic performances contributed. They used the Morte in slow tempo rarely. In one of the few cases of a Morte in an operatic slow introduction, Giovanni Paisiello probably intended to make fun of it. Socrate immaginario (Naples, 1775) is a comedy about a rich man, Don Tammaro, whose obsessive reading of ancient Greek philosophy has begun to affect his mind; he now believes that he himself is a philosopher. Hoping to shock him back to sanity, Don Tammaro's relatives play a trick on him. In a wonderful parody of the underworld scene in Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, they pretend to be furies. Terror-stricken, Don Tammaro is cured of his obsession with ancient Greece.

Socrate immaginario depicts the ancient abode of the dead, but all in fun. Similarly, the overture begins with a musical symbol of death, but in a form that keeps us from taking it seriously. The cheerful Allegro con spirito is preceded by a three-bar introduction labelled Maestoso, again featuring the dotted rhythms of a French overture (Example 12). This Maestoso is a six-stage Morte, but an odd one: it ends (as signalled by a fermata) on the augmented-sixth chord, instead of on the dominant chord that we expect. Paisiello resolves the augmented sixth only at the beginning of the Allegro con spirito. But the resolution is also strange. Instead of moving outward to an octave, the diverging outer parts suddenly converge onto a single G. Together, these quirks may be hinting that this opera is going to make fun of musical conventions that we might have taken seriously in the church. (As if to make sure his audience gets the joke, Paisiello repeats it, pianissimo, a little later in the overture.)

Example 12 Giovanni Paisiello, Socrate immaginario (Naples, 1775), overture, bars 1–6 (from the autograph in I-Nc, Rari 3.2.3, available on the website Internet Culturale, <www.internetculturale.it>)

The overture to Mozart's Don Giovanni begins with another slow introduction that the composer might have intended as a parody. Working on a grand scale, Mozart presents much of the music that will accompany the arrival of the Stone Guest near the end of the opera. That music includes a passage (‘Don Giovanni, a cenar teco / M’invitasti, e son venuto’) with a descending diatonic fourth in the bass: D–C–B♭–A. In presenting that passage in the overture, Mozart enriched the harmony and chromaticized the bass and treble: in other words, he turned it into a Morte (Example 13). Mozart's Morte is as unusual as Paisiello’s, but in a completely different way. The diverging chromatic lines are there, but the ascent in the treble is tentative, interrupted by detours. Instead of the five or six chords that make up most manifestations of the Morte, Mozart wrote eight chords, imbuing the old schema with new mystery and complexity. Even so, the Molto allegro in D major quickly dissipates the horror evoked earlier and reminds listeners that they have come to theatre for the performance of an opera, not the celebration of a Requiem Mass. In retrospect, they might conclude that with this extraordinary Morte Mozart was playing a joke on them.

Example 13 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Don Giovanni (1787), overture, bars 5–11 (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 2, volume 5/17, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1968)). Used by permission

THE MORTE AS A MELODY OR PART OF A MELODY

The celebrated mezzo-soprano Carlo Broschi (better known as Farinelli) took up Hasse's ‘Pallido il sole’ (Example 1) and made it one of his trademark arias, greatly enhancing its fame throughout Europe. He later told the historian Charles Burney that at the court of Spain he tried to cure the mentally ill King Philip V by singing to him the same four arias, including ‘Pallido il sole’, every evening for a decade. Even if the tale is not literally true, it must have increased the aria's notoriety.

The fame of ‘Pallido il sole’ probably encouraged other musicians to use the Morte as the primarily melodic material of movements, instrumental as well as vocal. A few composers began melodies with the Morte, as Hasse had done. A more common strategy was to introduce the Morte a little later, as a subsequent phrase in a melody consisting of several segments. Using Gjerdingen's terminology, we might say that the Morte served much more often as a riposte than as an opening gambit.Footnote 24

Carl Heinrich Graun, a composer in the employ of King Frederick the Great of Prussia and music director of the Berlin court opera, was a skilful imitator of Hasse. Twenty-five years after the first performance of ‘Pallido il sole’, it was still a source of inspiration for Graun in composing an aria in Montezuma (Berlin, 1755). Montezuma's wife Eupaforice violently rejects the amorous advances of Hernán Cortés in the aria ‘Barbaro che mi sei’. She calls him a barbarian, a ‘cruel object of horror’ (‘fiero d’orrore oggetto’; see Example 14). After an opening exclamation and an orchestral flourish, a six-stage Morte that unfolds very much like Hasse's (major-mode context, one chord per bar) expresses Eupaforice's revulsion. The half cadences that follow, without the augmented sixth, are much less potent; they serve merely as musical question marks.

Example 14 Carl Heinrich Graun, Montezuma (Berlin, 1755), ‘Barbaro che mi sei’, bars 1–12. Translation: ‘Barbarian that you are to me, cruel object of horror, you wish to speak to me of love?’ (based on Denkmäler deutscher Tonkunst, series 1, volume 15, ed. Albert Mayer-Reinach (Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1904), available on International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), <www.imslp.org>)

Another musician who learned much from Hasse was Marianna Martines (1744–1812), a Viennese amateur singer, keyboard player and composer. She studied composition with Giuseppe Bonno, a Viennese court musician who had himself studied in Naples with Francesco Durante and Leonardo Leo – giving her an impeccable pedigree in the galant tradition.Footnote 25 Her mad scene ‘Berenice, ah che fai’, on a text from Metastasio's Antigono, makes powerful use of the Morte.Footnote 26 Berenice, an Egyptian princess, has been promised in marriage to the King of Macedonia. But she loves the king's son Demetrio, who tells her that he will kill himself if she marries the king. Alone, Berenice becomes delirious, imagining Demetrio's ghost. In the aria ‘Perché, se tanti siete’ (Example 15) she asks for death. Like Hasse and Graun, Martines used a Morte for the opening melody. But instead of letting a six-stage Morte dominate the melody, she squeezed a five-stage Morte into just one of three short phrase units, where it underlines the word ‘delirar’.

Example 15 Marianna Martines, ‘Berenice, ah che fai’, from the Scelta d’arie composte per suo diletto da Marianna Martines (Vienna, c1767), bars 101–106. Translation (of the aria's first stanza): ‘Why, if you are so numerous that you make me rave, why do you not kill me, emotions of my heart?’ (transcribed in Irving Godt, Marianna Martines: A Woman Composer in the Vienna of Mozart and Haydn, edited with contributions by John A. Rice (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2010), 68)

C. P. E. Bach worked for much of his life at the court of Frederick the Great, where – thanks largely to Graun – Hasse's galant operatic language was an essential part of the musical culture. Not surprisingly, Bach used a wide variety of galant schemata in his compositions, often subjecting them to what Gjerdingen has called ‘flamboyant and willful manipulations’.Footnote 27 In the fourth keyboard sonata of the set that he dedicated to Frederick – the so-called Prussian Sonatas – he integrated a Morte into an opening melody based on two other schemata (Example 16). Like the melody by Martines quoted in Example 15, Bach's melody begins with three short phrase units – in Bach's case, units of one bar each. In a miniature example of the ABB melody that galant composers loved, each phrase is based on a galant schema: one Heartz followed by two Meyers.Footnote 28 While Martines used the Morte as one of her three opening phrases, Bach placed it directly after the three opening phrases, in a kind of appendage, with a quirky texture of quickly shifting registers. Bach presents the Morte twice: the first time incomplete (the ascending line in the treble is mostly missing), the second time more easily recognizable. Here, as often in Bach's music, we can sense an improvisatory quality, as if Bach were inventing the Morte as he composed.

Example 16 C. P. E. Bach, ‘Prussian Sonatas’ (Berlin, 1742), No. 4/i, bars 1–6 (Sei sonate per cembalo che all’Augusta Maestà di Federico II Re di Prussia D. D. D. l’autore Carlo Filippo Emanuele Bach (Nuremberg: Schmid[, 1742]), available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

The Morte in the main theme of Mozart's String Quartet in D minor k421 gives listeners a similar impression of emerging organically from what came before it. The opening melody unfolds in two four-bar phrases, the second answering the first. In the first phrase the bass descends diatonically from the first scale degree down to the fifth (D–C–B♭–A: a straightforward minor-mode lament bass) before cadencing;Footnote 29 in the second phrase, Mozart transforms that accompaniment into a Morte, but with the ascending chromatic line buried within the texture (Example 17). The difference between the two phrases resembles the difference (mentioned above) between the music that accompanies the entrance of the Commendatore at the end of Don Giovanni – a diatonic lament in D minor – and the elaboration of that music into a (somewhat disguised) Morte at the beginning of the overture.

Example 17 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, String Quartet in D minor k421/i, bars 5–8 (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 8, volume 20/Abt. 1/2, ed. Ludwig Finscher (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1962)). Used by permission

THE MORTE IN MODULATORY AND CONNECTING MATERIAL

In Andromaca (Naples, 1742) Leonardo Leo depicted a passionate young woman in an extreme state of anger and despair. Andromaca (Andromache, widow of the Trojan hero Hector) faces a fate similar to that of the Aztec queen Eupaforice in Graun's Montezuma, and she reacts to it in much the same way. In the aria ‘Prendi quel ferro, o barbaro’ she berates the Greek king Pirro (Pyrrhus), offering him a sword and demanding death. Near the middle of the aria, overcome by emotion, she can utter only short exclamations, their increasing urgency conveyed by the rising vocal line of the Morte (Example 18). Composers of instrumental music valued the Morte as highly as opera composers did for its ability to bring energy and excitement to modulatory and connecting passages like this one. We find the Morte quite often in development sections in sonata-form movements, but occasionally also in bridge passages in expositions and recapitulations.

Example 18 Leonardo Leo, Andromaca (Naples, 1742), ‘Prendi quel ferro, o barbaro’, bars 62–69; the dynamic indication ‘pf’ probably means ‘poco forte’. Translation: ‘Barbarian, take this sword and stab me. Ah son, ah barbarian, ah torment!’ (based on a manuscript full score, I-Nc, Rari 1.6.16–17, available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

The Morte's association with the serious, the important and the extraordinary sometimes results in its expected destination, a major chord built on the fifth degree of the local tonic, being itself elaborated at great length. A good example is in Mozart's overture to his early opera Lucio Silla. In the first movement's exposition Mozart sets up the medial caesura with a Morte derived motivically from the first theme (Example 19). The grandeur of this gesture makes the great length of the Ponte that follows seem appropriate. This passage anticipates quite closely the one by Gyrowetz quoted in Example 4. Although Mozart's passage occurs in an exposition and Gyrowetz's in a recapitulation, their function is exactly the same: to set the stage for the second theme.

Example 19 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Lucio Silla (Milan, 1772), overture, i, bars 19–29 (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 7/1, ed. Kathleen Kuzmick Hansell (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

We might expect composers to use the Morte for a similar purpose in the development section, namely to set the stage for the recapitulation and the return of the tonic key by establishing its dominant. But the Morte tends to serve other purposes in the development. We often find it attached to a musical gesture or passage that ends melodically on ❶ or ❸. The Morte serves as a kind of pendant, causing the passage as a whole to end on the local dominant rather than the tonic. In doing this, it helps to maintain or even increase the music's forward momentum. Perhaps because the Morte is usually preceded by a dominant chord, composers preferred the five-stage Morte in these contexts.

One of the simplest musical gestures to which composers attached the Morte as a pendant is a V–I progression. The development section of the first movement of Haydn's Symphony No. 7 in C major, ‘Le Midi’ (the second of three symphonies on the times of day that he wrote in 1761), contains a passage in A minor in which a repeated alternation of i and V6 threatens to bring the music to a stop (despite the solo violinist's exertions) until a Morte suddenly jacks up the energy (Example 20; the tonal plan here is the same as the one Weigl used thirty years later in the passage quoted in Example 3).Footnote 30

Example 20 Joseph Haydn, Symphony No. 7 in C major, ‘Le Midi’ (1761), i, bars 76–85 (based on Joseph Haydn Werke, series 1, volume 3, ed. Jürgen Braun and Sonja Gerlach (Munich: Henle, 1990)). Used by permission

Another schema that sometimes takes the Morte as an appendage in development sections is the Fonte, a two-stage sequence that tonicizes first a minor key and then the major key a whole step lower.Footnote 31 Composers liked to use the Fonte at the beginning of the second part of binary-form movements. Mozart begins the second part of the first movement of the Sonata in E flat major, k282, with an F minor/E flat major Fonte in which the second stage is varied to an unusual degree (Example 21).Footnote 32 Probably wanting to avoid a strong sense of arrival on the tonic so soon after the beginning of the second part, Mozart elides the end of the Fonte to the beginning of a Morte that, in turn, sets up a Ponte. Taking care to integrate the Morte into the passage as a whole, Mozart derives its motivic material from the second stage of the preceding Fonte, transferring the slurred semiquaver groups from treble to bass.

Example 21 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Sonata in E flat major, k282/i, bars 16–22 (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 9, volume 25/1, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)). Used by permission

The usefulness of the Morte as a means of maintaining or even increasing musical momentum at points of arrival is illustrated nicely by Mozart in the finale of the Piano Concerto in E flat major k449, a movement in sonata-rondo form. In the development (the C section, in rondo terms), Mozart used a circle-of-fifths Prinner in C minor to spin out seven bars of piano triplets.Footnote 33 The destination is clear (the C minor chord at the beginning of bar 162), but the listener has no way of knowing that Mozart will take off again – like a pilot practising landings – by means of a Morte (Example 22).

Example 22 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Piano Concerto in E flat major k449/iii, bars 156–165, piano part only (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/4, ed. Marius Flothuis (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1975)). Used by permission

The Prinner/Morte combination was hardly invented by Mozart, who could have found good examples of it in vocal music composed during his childhood. Andrea Bernasconi, maestro di cappella at the Electoral court of Munich from 1755 to 1784, used it to good effect in his Miserere in D minor, almost certainly composed during the 1750s. In the aria ‘Amplius lava me’ a circle-of-fifths Prinner provides the framework for coloratura that dramatizes the word ‘semper’ – coloratura extended by a Morte and a Ponte (Example 23).Footnote 34

Example 23 Andrea Bernasconi, Miserere in D minor, ‘Amplius lava me’, bars 51–57 (based on the full score, ed. Christoph Riedo (Adliswil: Edition Kunzelmann, 2009)). Used by permission

THE MORTE WITH UNEXPECTED EXTENSIONS

The conventions associated with the Morte called for it to end on the dominant of the key in which it began. An important means by which composers subverted those conventions was to take the player and listener somewhere beyond that expected destination.Footnote 35

An obvious way of extending the diverging chromatic lines beyond their normal limit was to elide the end of the Morte with a schema that Gjerdingen has called the Passo Indietro.Footnote 36 The dominant harmony at the end of the Morte yields to the tonic with a bass that cancels the earlier chromatically raised fourth in the treble as it descends from the fifth scale degree to the third. Niccolo Jommelli provided a clear example of this technique in his Requiem (Example 24).

Example 24 Niccolo Jommelli, Requiem (1756), Dies irae, bars 55–58. Translation: ‘What shall a wretch like me say then? Who shall intercede for me, when even the just need mercy?’ (piano-vocal score by O. H. Lange (Braunschweig: Litolff, no date), available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

Christoph Gluck achieved a more powerful effect with a similar extension of the Morte by calling attention to it with a fermata. In 1765, in the Burgtheater in Vienna, the choreographer Gasparo Angiolini presented Sémiramis, a ‘ballet pantomime tragique’ with music by Gluck. Based on Voltaire's spoken tragedy of the same title, Angiolini's ballet tells a story of a murder, a ghost, incest and matricide. Sémiramis, Queen of Persia, having killed her husband Ninus, has fallen in love with a young soldier, Ninias, unaware that he is her son. In the third and final act, the ghost of Ninus draws Sémiramis into his tomb. The high priests, unaware that the queen is in the tomb, order Ninias to enter and to kill whomever he finds. A few moments later, Ninias emerges from the tomb, confused, with a blood-stained dagger. He has just stabbed his mother.Footnote 37

Although not every part of Gluck's score can be connected definitively with a precise moment in the drama, it seems likely that Gluck's No. 12, an Adagio that begins in D minor and ends in G minor (Example 25), is meant to be heard while Ninias is in the tomb.Footnote 38 Gluck placed a Morte near the middle of this number (bars 9–13). If that Morte signals to the audience the approach of the moment when Ninias stabs Sémiramis, then the deed itself might by accompanied by the surprising diminished-seventh chord, with a fermata, which constitutes the extension of the Morte beyond its normal range (bar 14). Twenty-two years after the premiere of Sémiramis, Mozart depicted the wounding of the Commendatore with a diminished-seventh chord on a fermata.Footnote 39

Example 25 Christoph Gluck, Sémiramis (Vienna, 1765), No. 12, bars 1–18 (based on manuscript full score in D-DS, Mus. Ms. 340, available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

Gluck's Morte, by going beyond the normal limits of the schema – and calling attention to this transgression by means of the fermata – conveys not only the tragic nature of the events unfolding on stage, but also a purely musical sense of instability, unpredictability and dynamism. Analogous violations of convention in sonatas and concertos similarly stand out as moments of exceptional dramatic excitement.

Haydn, like Mozart (in Example 22) and Bernasconi (in Example 23), liked the effect of eliding the Morte to the end of a Prinner; he did so in the Sonata in C major hXVI:21 (1773). In the development section of the finale (Example 26) Haydn elaborated the Prinner–Morte complex in the same key (C minor) and in the same number of bars as Mozart (compare Examples 22 and 26). But in one respect Haydn's passage differs greatly from Mozart’s. After a bar of the G major harmony that one expects at the end of a Morte in C minor, Haydn allows the diverging lines to continue – in the treble up a half step to G♯, in the bass down a whole step and then a half step to E. The resulting E major chord replaces the Morte's G major chord and serves as the dominant of A minor, the key of the next passage in the development. The logic of the Morte's diverging lines allows Haydn to move quickly between two rather distantly related keys.

Example 26 Joseph Haydn, Sonata in C major hXVI/21:iii, bars 56–71 (Joseph Haydn Werke, series 18, volume 2, ed. Georg Feder (Munich: Henle, 1970)). Used by permission

Mozart, of course, was no less daring a transgressor of tonal conventions than Haydn. The development section of the first movement of the Piano Concerto in A major k414 contains a passage in F sharp minor that culminates in a magnificent contrapuntal Prinner (bars 180–188). Once again Mozart avoided the danger of the music seeming to come to a stop at the end of the Prinner by eliding it to a Morte (Example 27). But this time he allowed the diverging lines to continue past the C♯ in octaves that should have been their final destination, up to D in the treble and down to A in the bass. With this extension the Morte overlaps with and (in terms of function) gives way to a Passo Indietro, exactly as in the passage in Jommelli's Requiem quoted in Example 24.

Example 27 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Piano Concerto in A major k414/i, bars 188–195, keyboard part only (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, volume 15/3, ed. Christoph Wolff (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1976)). Used by permission

One surprise leads to another, as a cadence in F sharp minor leads – most unusually – to a second Morte, this time with the ascending chromatic line eccentrically realized as a long trill. Again the diverging lines go ‘too far’ – but this time to pitches that frame a dominant-seventh chord in the key of the recapitulation that will begin two bars later (at bar 196, not shown in the example). Like Haydn in the Sonata in C major, Mozart began a Morte in a key different from the one to which he intended to modulate, and extended it beyond its conventional boundary so as to replace the dominant chord with which the Morte would normally end with the dominant of another key.

Earlier I described the beginning of Mozart's Coronation Mass (Example 8) as promising a Morte but delivering a Le-Sol-Fi-Sol. That description should not leave the impression that it was impossible to use these two schemata together. Bernasconi's Miserere in D minor opens with a Morte with unusually free voice leading: the ascending chromatic line migrates from alto to soprano to tenor, and the bass is suspended before it begins its descent (Example 28). The progression i–ii![]() ${{}^{\smash{\raise-2pt\hbox{$\scriptsize{^4}$}}}}{\begin{array}{c}{{\!\!}}\\[-5pt]{\!\!\!\hspace*{-.5pt}{^2}}\end{array}}$–V6 is characteristic of the beginning of the schema (often used in the eighteenth century as an opening gambit) that elsewhere I have called the Lully.Footnote 40 But in bar 11 Bernasconi replaces the tonic chord that we expect as the fourth and final stage of the Lully with a chord characteristic of the third stage of a six-stage Morte. A bar later, he elides the Morte with a Le-Sol-Fi-Sol, allowing the chromatic passage to continue a bar longer than we expect.

${{}^{\smash{\raise-2pt\hbox{$\scriptsize{^4}$}}}}{\begin{array}{c}{{\!\!}}\\[-5pt]{\!\!\!\hspace*{-.5pt}{^2}}\end{array}}$–V6 is characteristic of the beginning of the schema (often used in the eighteenth century as an opening gambit) that elsewhere I have called the Lully.Footnote 40 But in bar 11 Bernasconi replaces the tonic chord that we expect as the fourth and final stage of the Lully with a chord characteristic of the third stage of a six-stage Morte. A bar later, he elides the Morte with a Le-Sol-Fi-Sol, allowing the chromatic passage to continue a bar longer than we expect.

Example 28 Bernasconi, Miserere, ‘Miserere mei Deus’, bars 8–14

Mozart extended a six-stage Morte with exactly the same technique in the finale of his Sonata in C minor, k457; and he too made the beginning of the Morte as ambiguous as its ending. The second episode (or development section) in this sonata-rondo contains a passage in C minor (beginning at bar 197) that, like the beginning of the Coronation Mass, sounds as if it will be a six-stage Morte (Example 29). But the augmented sixth so characteristic of the Morte is missing. The bass, after descending chromatically to the flat sixth (A♭), leaps down a fourth to the flat third (E♭). That forces us to reinterpret what we have heard as a different schema entirely: a scalar descent from 1 down to 6 followed by a leap of a fourth down is characteristic of the Romanesca (as in the first two bars of Leo's ‘Prendi quel ferro’, Example 18 above, where the leap of a fourth down is achieved after a register transfer of the G). After a cadence in C minor, the Romanesca begins again, or seems to, but this time the chromatic descent continues down to G. We must change our minds again: this is a Morte. But not an ordinary Morte: the descending line continues past G to F♯, and eventually back to G. That encourages us, in retrospect, to hear the bass's A♭–G–F♯–G as a Le-Sol-Fi-Sol. In the space of seventeen bars of Allegro assai, Mozart challenges us with an intensive play of schemata – a stimulating guessing game in which the Morte plays a crucial role.Footnote 41 In his very last music Mozart was still thinking of ways to extend the Morte. In the unfinished ‘Lacrimosa’ of the Requiem, the beginning of a Morte in C minor leads, by a wonderful bit of chromatic sleight of hand, to the end of a Morte in D minor (Example 30).

Example 29 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Sonata in C minor, k457/iii, bars 197–213 (Fantaisie et Sonate pour le forte-piano composées pour Madame Therese de Trattnern par le maitre de chapelle W. A. Mozart, oeuvre XI (Vienna: Artaria[, 1785]), available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

Example 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Requiem (fragment), ‘Lacrimosa’, bars 5–8 (based on the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 1, volume 1/Abt. 2/1, ed. Leopold Nowak (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1965)). Used by permission

I end this brief – far from comprehensive – survey of the Morte with yet another Morte in C minor: the theme that Beethoven used in his Thirty-Two Variations, WoO 80, discussed perceptively by Caplin as an example of the Lament (as both schema and topic).Footnote 42 Despite the antique qualities of the theme (especially its insistence on the sarabande rhythm), Beethoven aggressively attacks the Morte's conventions, not only by taking the diverging lines beyond the fifth scale degree, but also with an additional one–two harmonic punch. First, like Mozart in Example 30 (bar 8), he delays the expected dominant chord by means of a ![]() ${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{6}}\\[-2pt]{^{4}}\end{array}}$. Then, instead of resolving the

${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{6}}\\[-2pt]{^{4}}\end{array}}$. Then, instead of resolving the ![]() ${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{6}}\\[-2pt]{^{4}}\end{array}}$ to a

${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{6}}\\[-2pt]{^{4}}\end{array}}$ to a ![]() ${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{5}}\\[-2pt]{^{3}}\end{array}}$, as in Example 30, or using the diminished chord that we might have expected from our acquaintance with Morte extensions by Jommelli, Gluck, Haydn and Mozart (Examples 24, 25, 26 and 27), Beethoven's music surprises us again, with a sforzando subdominant chord, followed finally by a surprisingly prim, almost comically anti-climactic cadence in the tonic, piano (Example 31).

${}{\begin{array}{c}{_{5}}\\[-2pt]{^{3}}\end{array}}$, as in Example 30, or using the diminished chord that we might have expected from our acquaintance with Morte extensions by Jommelli, Gluck, Haydn and Mozart (Examples 24, 25, 26 and 27), Beethoven's music surprises us again, with a sforzando subdominant chord, followed finally by a surprisingly prim, almost comically anti-climactic cadence in the tonic, piano (Example 31).

Example 31 Ludwig van Beethoven, Thirty-Two Variations on a Theme in C minor, WoO80 (1806), bars 1–8 (Vienna: Kunst und Industrie Comptoir[, 1806], available on IMSLP, <www.imslp.org>)

Beethoven wrote the Thirty-Two Variations in 1806, the same year in which Hummel wrote the Mass in C major that begins with the sombre and majestic Morte quoted above in Example 9. With these works, our schema entered the nineteenth century. During the next few decades composers continued to explore the harmonic and melodic possibilities offered by chromatic wedge progressions. For many of the passages with diverging chromatic lines in nineteenth-century music the term Morte is no longer appropriate. These passages offer us different – but no less fascinating – analytical and interpretative challenges.