1. Introduction

Pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic testing, which identify genetic variants that can help predict drug efficacy and/or toxicity, are important contributors to the field of precision medicine by clarifying appropriate treatments for specific disease subtypes. Recognizing potential differences in terminology, depending on whether single drug–gene interactions or drug responses from multiple genes are referred to, we will use PGx as an abbreviation inclusive of both pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic approaches in this review.

Response rates of patients to medications ranges widely by therapeutic class, from ~80% for analgesics to ~25% for oncology therapeutics (Spear et al., Reference Spear, Heath-Chiozzi and Huff2001). In addition to the varied response rates, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) also vary widely and are of significant clinical concern. ADRs are estimated to occur in excess of 2 million events in the US each year and result in over 100 000 deaths annually (Lazarou et al., Reference Lazarou, Pomeranz and Corey1998). Although genetic variation seldom accounts for all of the differences seen in patient treatment responses and ADRs, the objectives of PGx testing are to utilize genomic information to tailor pharmacotherapy to the patient's predicted treatment response in order to improve drug efficacy, real-world effectiveness and safety. Genetic information (such as DNA sequence, gene expression and copy number) is used to explain inter-individual differences in drug metabolism (pharmacokinetics) and responses (pharmacodynamics). Expectations are that PGx testing will target drug therapies to the appropriate patients in order to maximize benefits and to minimize harms, as well as costs. The use of PGx testing has already begun for many drugs in development, and the marketing of drugs currently available may soon suggest or require that PGx testing is done before a patient ever begins a treatment regimen.

PGx testing is currently available for a wide range of health problems including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, mental health disorders and infectious diseases. Tangible benefits to patients are currently being observed on a daily basis, including improved outcomes and reduced total health care costs. However, PGx-guided therapy faces many barriers to full integration into clinical practice and acceptance by stakeholders, whether practitioner, patient or payer.

2. Purpose of this review

Each stakeholder has a unique perspective on the role of PGx testing, although all are similarly challenged with demonstrating or appraising its cost-to-benefit value. Coverage by insurers is a critical step in achieving widespread adoption of PGx testing, and the current and future landscape relative to reimbursement is a focus throughout this review. In the following sections, trends in PGx testing utilization and uptake by payers in real-world practice are discussed, the role of pharmacoeconomics in assessing cost-effectiveness is highlighted using a case study in psychiatric care, and several issues that will affect adoption of PGx testing in the US over the next few years are reviewed. The purpose of this review is to increase the understanding of the current state of PGx testing, discuss key factors impacting its acceptance, and to foster additional research and evidence generation in the field.

3. Current real-world PGx-testing practice

Over 140 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs have PGx information in their labelling (FDA, 2014 b ) that refers to pharmacodynamic relationships, such as identification of a specific gene that correlates with a drug mechanism of action, and/or pharmacokinetic mechanisms that describe drug metabolism effects on efficacy and ADRs. For a limited number of drugs, labelling mandates PGx testing and specific actions are taken based on the PGx information (examples, primarily highlighting the area of oncology, are provided in Table 1(a)). Where PGx testing has been identified as necessary for the safe and effective use of the corresponding therapy, companion diagnostic tests have been approved (premarket approval) or cleared (equivalent to marketed device) by the FDA (FDA, 2014 a ) (examples provided in Table 1(a)). In these situations, the cost for testing indicated by the FDA is generally reimbursed by most insurance plans (Hresko & Haga, Reference Hresko and Haga2012; Graf et al., Reference Graf, Needham, Teed and Brown2013). This is well illustrated in the field of oncology. Since many cancers are not viewed as a single disease, but rather as a group of several subtypes, each with a distinct molecular signature, identifying the genomes of the malignancy and of the patient can aid in effective and safe treatment.

Table 1. Examples of drugs with PGx biomarker and use, labelling status, companion PGx test, and payer coverage.

Other drugs have labelling with PGx specific guidelines for a patient subtype but don't have a required companion PGx diagnostic. For example, ivacaftor is approved for cystic fibrosis therapy specifically for patients with the G551D mutation, which occurs in 4% of patients (Clancy et al., Reference Clancy, Johnson, Yee, McDonagh, Caudle, Klein, Cannavo and Giacomini2014). The majority of cystic fibrosis patients have a mutation panel performed at the time of diagnosis as an existing standard of care; labelling guidelines require an FDA approved mutation test in cases where the genotype is not known (Vertex, 2014). In either case, costs are typically reimbursed (Hresko & Haga, Reference Hresko and Haga2012; Graf et al., Reference Graf, Needham, Teed and Brown2013). Examples of other drugs with recommended, but not mandated, PGx guidelines are shown in Table 1(b). While these examples are not comprehensive, they illustrate the diversity of drugs and therapeutic areas where the FDA has approved or cleared PGx tests, but the companion testing is not required prior to prescribing. Coverage for testing in these cases varies widely by insurers.

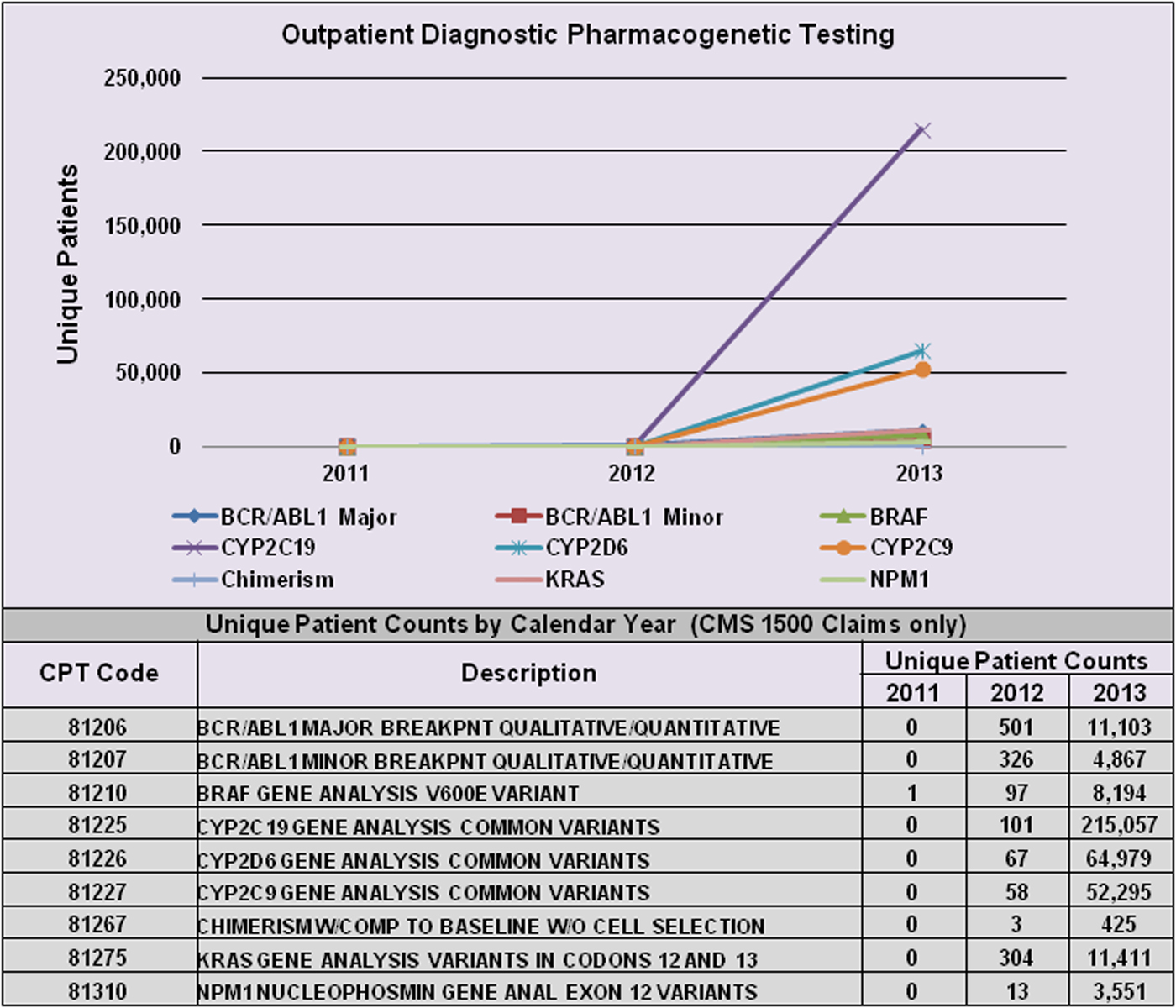

However, PGx-specific labelling for many drugs is informational only, and testing is neither mandated nor recommended prior to prescribing. Table 1(c) provides examples of two such cases (rovustatin and warfarin). In these cases, PGx testing has generally not been endorsed by expert committees since the supporting evidence has been judged statistically insufficient, and consequently, insurers will not pay for it (Hresko & Haga, Reference Hresko and Haga2012; Graf et al., Reference Graf, Needham, Teed and Brown2013). This is particularly relevant for tests related to genotyping for metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms for use with drugs having narrow therapeutic ratios and/or serious toxic effects. Figure 1 illustrates the growth of PGx testing in this area between 2011 and 2013 using data available from a private practitioner medical claims database (Symphony Health Solutions). FDA approval or clearance is not a requirement, so many are laboratory developed tests (i.e. offered and used within a single laboratory) that do not undergo FDA review. However, there is currently new FDA draft guidance in review that may change the regulatory oversight of laboratory developed tests (FDA, 2015 b ). For acceptance and reimbursement of these tests by payers, comparisons with standard methods of assessing therapeutic drug safety and efficacy are needed, as well as subsequent demonstration of value. Since factors other than genetic polymorphisms (including race, gender, epigenetic factors and lifestyle choices) can have a significant effect on drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, it remains unclear whether PGx testing would eliminate the need for simultaneous use of other methods of therapeutic drug monitoring.

Fig. 1. Increase in PGx testing from 2011–2013. Figure shows the change in unique patient counts for selected assays from 2011 through 2013. On 1 January 2012, Medicare requested that claims for Molecular Pathology Procedures reflect both the existing CPT ‘stacked’ test codes that are required for payment, and the new single CPT test code. Patient counts are based on CMS 1500 claims and are courtesy of Symphony Health Solutions private practitioner medical claims database. CPT, Current Procedural Terminology.

In the area of therapeutic drug monitoring a recent example with potentially broad applications has been the use of PGx testing to guide warfarin anticoagulation therapy for the prevention of thromboembolic events. Two genes have been identified that play a role in outcomes related to warfarin therapy: CYP2C9 is a gene for an enzyme that is primarily responsible for the metabolism of warfarin, and VKORC1 codes for the warfarin drug target. The current warfarin label acknowledges that dose requirements are influenced by CYP2C9 and VKORC1 and states that genotypic information, when available, can assist in selecting the starting dose, but does not recommend routine PGx testing for determining initial or maintenance doses. Several diagnostic tests are cleared by the FDA for monitoring of warfarin anticoagulation (FDA, 2015 a ). However, the lack of standardization of these tests in detecting the relevant CYP2C9 variants, lack of understanding of the role of specific VKORC haplotypes and varying result turnaround times (1 to 8 hours) have raised skepticism regarding their decision-making utility (Rosove & Grody, Reference Rosove and Grody2009). Randomized controlled clinical trials examining use of PGx-guided warfarin dosing compared with current clinical data monitoring approaches have shown inconsistent results in stabilization of treatment responses, reducing the number of necessary office visits or decreasing risk of bleeding events. Consequently, consensus guidelines (e.g. American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Medical Genetics), do not advise use of genetic testing to guide warfarin dosing (Flockhart et al., Reference Flockhart, O'Kane, Williams, Watson, Gage, Gandolfi, King, Lyon, Nussbaum, Schulman and Veenstra2008; Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Akl, Crowther, Gutterman and Schuunemann2012). As a result, most payers (including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)) are reluctant to reimburse for testing for PGx-guided warfarin therapy. However, it is unclear what role patient compliance with treatment contributes to the inconsistent efficacy and health outcomes, and studies addressing non-genomic factors' influence on treatment outcomes are critical to justify modification to standards of care and reimbursement decisions.

The drug clopidogrel, an anti-platelet therapy, is another example where genotype-specific labelling guidelines do not meet the indeterminate threshold for standard of care testing. CYP2C19 genotyping can determine normal, poor, intermediate, rapid and ultra-rapid metabolizers of clopidogrel in order to identify patients who may benefit from non-standard, ‘recommended’ dosing or have better responses to an alternative drug. In 2010, the FDA added a boxed warning to clopidogrel labelling alerting patients and health care professionals that the drug can be less effective in people who cannot metabolize the drug to convert it to its active form, and modified the warning to include guidance on data suggesting adverse cardiovascular event risks for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients with the CYP2C19 genotype following a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2013 b ). However, the boxed warning does not mandate genetic testing, is not specific on the exact patient profile to benefit from genetic testing, and is vague on alternative treatment approaches in poor metabolizers. Consensus guidelines issued by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) express concerns about the lack of outcomes data documenting the benefit of routine genotyping and concluded the available literature did not support CYP2C19 genotyping for all patients being prescribed clopidogrel (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Dehmer, Kaul, Leifer, O'Gara and Stein2010). AHA and ACC guidelines to date support CYP2C19 genotyping in ACS patients at high risk for poor outcomes after PCI or in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy for whom the genotype poses potential risk for reduced antiplatelet efficacy (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Sangkuhl, Stein, Hulot, Mega, Roden, Klein, Sabatine, Johnson and Shuldiner2013). Genotyping for one CYP2C19 polymorphism in patients prescribed clopidogrel is reimbursed by some payers (Hresko & Haga, Reference Hresko and Haga2012; Graf et al., Reference Graf, Needham, Teed and Brown2013).

Genetic testing has also been considered to mitigate the risk of serious adverse events with statins, which are generally safe and well tolerated and among the most widely prescribed medications (e.g. almost 50% of adults 65 years and older have statin prescriptions (CDC, 2013). Myopathy is the most common side effect and can result in life-threatening rhabdomyolysis with muscle damage and acute renal injury. Although mild myalgias may not result in any physical harm, they threaten patient adherence to statin therapy. The incidence of statin-associated myopathy varies between 1 and 5% in clinical trials, with a higher incidence observed in clinical practice (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Clarkson and Karas2003). There is a heritable component to the risk for statin-induced myopathy and the role for PGx testing in guiding statin pharmacotherapy is evolving, particularly for the solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1B1 (SLCO1B1) gene. Routine PGx testing for statin therapy is not recommended by current guidelines (Ramsey et al., Reference Ramsey, Johnson, Caudle, Haidar, Voora, Wilke, Maxwell, McLeod, Krauss, Roden, Feng, Cooper-DeHoff, Gong, Klein, Wadelius and Niemi2014; Talameh & Kitzmiller, Reference Talameh and Kitzmiller2014) nor covered by most payers. Additional studies are needed to determine clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of PGx testing in patient populations given factors including the type of statin (as pharmacokinetic profiles for each statin are unique), the dose and concomitant use of other drugs (Sorich et al., Reference Sorich, Wiese, O'Shea and Pekarsky2013; Talameh & Kitzmiller, Reference Talameh and Kitzmiller2014).

Inclusion of informational PGx tests by the FDA on the revised labels of many drugs without clear guidance on dosing recommendation and/or therapeutic alternatives by PGx result has led to confusion among providers, who are eager for guidance around an emerging technology with which they are largely unfamiliar. Professional organizations are attempting to educate and guide physicians on drug selection and dosing for drugs with PGx informational labelling. For example, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium has issued dosing guidelines taking into consideration patient genotype for warfarin, opioids, abacavir and other drugs with and without PGx informational labelling (CPIC, 2015). However, although these organizations can provide some level of guidance, challenges remain as there are limited nationally and internationally accepted standards around dosing decisions. Continued education of health care providers regarding the impact of metabolizer status and frequency of variants in a given population is needed to fully leverage PGx testing and information.

4. Pharmacoeconomic analyses to demonstrate value: case study of PGx-guided psychiatric intervention

The use of PGx testing needs to exhibit clinical, economic and quality of life benefits; demonstrating one or all of these values is critical to adoption among stakeholders. In addition to reducing side effects and ADRs, goals of PGx testing include lowering costs and improving patient compliance. When PGx testing results guide treatment decisions, positive treatment responses will be more quickly attained, which in turn, in theory, reduces the indirect and direct costs associated with failed treatment trials and ADRs. As long as the PGx testing costs and practitioner time for interpretation are lower than these indirect and direct costs, the net result is cost savings. In addition, patient quality of life improves when treatment failure and ADRs are reduced. While indirect costs are important considerations for providers and patients, payers are most influenced by evidence of direct impact, thus research has a multifaceted challenge of proving value on several levels. One well-established approach for determining value is to assess both costs and outcomes within pharmacoeconomic analyses. There have been relatively few published cost-effectiveness analyses of PGx interventions. The following example demonstrates how PGx-guided psychiatric intervention was associated with increased compliance with therapy and direct cost savings (Fagerness et al., Reference Fagerness, Fonseca, Hess, Scott, Gardner, Koffler, Fava, Perlis, Brennan and Lombard2014). While cost-effectiveness data are not the only information needed to influence acceptance of PGx testing by stakeholders, payers are particularly interested in these data, and the ability to use real-world claims and clinical databases is an efficient method to demonstrate utility in the absence of randomized clinical trials.

Known pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic variations exist that impact responses to common psychiatric medications (Burroughs et al., Reference Burroughs, Maxey and Levy2002). An estimated two-thirds of patients with depression will not respond adequately to first line treatment and more than one-third of patients will become treatment resistant (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Koretz, Merikangas, Rush, Walters and Wang2003; Souery et al., Reference Souery, Papakostas and Trivedi2006; Warden et al., Reference Warden, Rush, Trivedi, Fava and Wisniewski2007). Genetic variations affect efficacy and tolerability of psychotropics as a result of variable drug disposition, metabolism and transport (Evans & McLeod, Reference Evans and McLeod2003; Kao et al., Reference Kao, Fang, Zhao and Kuo2011; Porcelli et al., Reference Porcelli, Drago, Fabbri, Gibiino, Calati and Serretti2011; Salloum et al., Reference Salloum, McCarthy, Leckband and Kelsoe2014). Many antidepressants and antipsychotics show differences in plasma drug levels as a result of cytochrome P450 polymorphishms (e.g. CYP2D6 and CYP2C19) (Kirchheiner et al., Reference Kirchheiner, Nickchen, Bauer, Wong, Licinio, Roots and Brockmoller2004; Tansey et al., Reference Tansey, Guipponi, Hu, Domenici, Lewis, Malafosse, Wendland, Lewis, McGuffin and Uher2013). The Genecept™ Assay (Genomind) is a laboratory validated test used to analyse variations in both pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic genes associated with treatment response, side effects, metabolism, tolerability and overall efficacy of psychiatric medications (Kato & Serretti, Reference Kato and Serretti2010; Lencz et al., Reference Lencz, Robinson, Napolitano, Sevy, Kane, Goldman and Malhotra2010; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lencz and Malhotra2010; Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group, 2011; Bhat et al., Reference Bhat, Dao, Terrillion, Arad, Smith, Soldatov and Gould2012; Porcelli et al., Reference Porcelli, Fabbri and Serretti2012). Despite its commercial use for over 4 years in more than 30 000 patients, the Genecept Assay is considered ‘experimental’ by many insurers. Typical to challenges in this field, while this assay has accumulated multiple levels of data arguably supporting its utility, the evidence to overcome this label is rigorous, but paradoxically not well defined.

One such piece of evidence is a retrospective, observational study that assessed patient claims data to measure direct health costs as a result of patient and clinician access to genetic information during psychiatric treatment selection guided by the Genecept Assay (Fagerness et al., Reference Fagerness, Fonseca, Hess, Scott, Gardner, Koffler, Fava, Perlis, Brennan and Lombard2014). Genetic test results and pharmacy and medical claims were integrated at the patient level. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to identify case and control patients to reduce potential sources of bias (Baser, Reference Baser2006; Austin, Reference Austin2010; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Gardiner and Bradley2010; Austin, Reference Austin2011). PSM adjusted for covariates of patient demographics, payer type, medical data and treating practitioner's specialty, and identified 111 case and 222 matched control patients from pools of over 1000 case and 100 000 control patients. Patient's highest adherence levels pre-index vs. post-index were compared (index = date when genetic test results were available for tests and similar calendar date for controls). An observed increase in adherence to therapy in cases was associated with a significant decrease in overall costs associated with outpatient activity. Although pharmacy costs for cases increased relative to controls, likely due to consistent medication fills concomitant with improved medication adherence, the overall use of medical services decreased, and the relative cost savings over a 4-month follow-up period was 9·5%, or $562 per patient (Fagerness et al., Reference Fagerness, Fonseca, Hess, Scott, Gardner, Koffler, Fava, Perlis, Brennan and Lombard2014).

While randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard for clinical investigation, this example demonstrates how retrospective observational studies can use real-world clinical data to assess whether PGx-guided therapy can improve patient outcomes. This approach can assist in building the clinical and economic evidence base for PGx testing in order to provide information to stakeholders. To be effective in influencing uptake of PGx testing, health care providers will benefit from increasing awareness of the data on cost-effectiveness and economic utility of PGx.

5. Acceptance of PGx-guided therapy by insurers

(i) Increasing the evidence base of PGx testing

An important driver for uptake of PGx testing is insurance coverage and reimbursement.

A variety of factors are considered by insurers in formulating medical coverage policies for PGx testing, including availability of clinical guidelines, current use by physicians, patient interest and cost-effectiveness (Meckley & Neumann, Reference Meckley and Neumann2009) .The most consistent determining factor in coverage and reimbursement is conclusive evidence linking the use of the PGx test with health outcomes (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Wilson and Manzolillo2013). Government and private insurers rely on evidence of the impact of PGx testing on clinical and economic outcomes compared to an appropriate real-world alternative intervention in a prospective study. Currently, few PGx tests have evidence to support their clinical utility and consequently, they are considered experimental by most insurance plans and denied coverage. This behavior is consistent with insurers' approach to reimbursing drugs and medical procedures.

To avoid being considered experimental, providers of PGx tests need to make sure they perform robust studies and publish in peer-reviewed literature; i.e., conform to the norms established by insurers and standards groups. While randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard, it is possible to demonstrate clinical utility with other study models. As shown in the previous section, the use of claims and clinical data can establish benefits through the efficiency of data collection and the ability to measure direct and some indirect costs.

The CMS has established policies designed to bridge the divide between evidence-based coverage standards and emerging PGx technologies. The coverage with evidence development (CED) status is conferred by the CMS on promising PGx tests (as well as other technologies) (Tunis & Pearson, Reference Tunis and Pearson2006). This designation encourages use of the test in clinical trials by linking provisional coverage for promising technologies to the requirement for patient participation in a registry or clinical trial. CMS has assigned CED designation to PGx testing for warfarin, for example (CMS, 2014 a ). The designation encourages collection of real-world data to assess clinical utility and economic outcomes and may influence other payers to provide reimbursement for promising PGx tests in a similar manner.

(ii) Novel coverage and reimbursement models

Reimbursement levels for diagnostic tests, including PGx testing, are regulated by the CMS Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule. A new coding system and reimbursement plan enacted by CMS in 2014 introduced analyte-specific codes to identify individual tests (CMS, 2014 b ). PGx testing has been especially impacted by the new model. The ‘unstacking’ of diagnostic test codes has resulted in less bundling of tests and provided pricing transparency that has resulted in greater scrutiny by payers of PGx tests (Deverka, Reference Deverka2009). The prior billing system used stacked codes and many payers typically did not have visibility into which analyte a test examined or how practitioners used it. The increased transparency has provided the means and ability for payers to assess the many individual PGx tests on the market, although information regarding how a test is performed and how clinicians use the information is still insufficient. For example, in the gene CYP2D6, there are well over 20 variations that can influence how the gene will behave in any given person. However, with the new coding system, an insurance company does not know if one or 20 variants have been tested. This could lead to many issues for patients, as well as interpretation problems for the providers. Payers are hesitant to reimburse for a PGx test if the information generated does not change practitioner and patient practices or if results of PGx tests are ignored. As a result, insurers are turning to new coverage and payment models such as performance-based and risk-sharing models (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Garrison and Sullivan2009; Hresko & Haga, Reference Hresko and Haga2012).

A performance-based model was tested by UnitedHealthcare in its approach to coverage of Genomic Health's Oncotype DX®. Oncotype DX breast cancer assay is a PGx test shown to aid in oncologists' decision-making on which patients with early breast cancer are most likely to benefit from chemotherapy (Dowsett et al., Reference Dowsett, Cuzick, Wale, Forbes, Mallon, Salter, Quinn, Dunbier, Baum, Buzdar, Howell, Bugarini, Baehner and Shak2010). Testing was expected to reduce inappropriate use of chemotherapy, but little data existed to support that assertion. UnitedHealthcare wanted evidence that they were getting sufficient value and cost offsets to warrant the coverage and reimbursement amount for the test. To help achieve this goal, an internal study was conducted on the proportion of women whose treatment choice coincided with the PGx test results (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Garrison and Sullivan2009). UnitedHealthcare monitored use of the test, and if clinicians did not take action based on the test results, the reimbursement amount was renegotiated to align with the actual value received.

Coverage and reimbursement models will likely continue to evolve to hold patients and health care providers more accountable for results of PGx testing. For these new models to work effectively, patient education is needed, as they will have to be involved in the testing and treatment paradigms and potentially incur costs based on these decisions. This is analogous to other areas where patients may elect to pay out-of-pocket when guidelines and insurance coverage are out-paced by advancing research/technology and perceived value in the marketplace. Mammogram reports are now required to include information on breast tissue density. Women with dense breast tissue are 4–5 times as likely to get breast cancer than women with low breast density (Yaghjyan et al., Reference Yaghjyan, Colditz, Collins, Schnitt, Rosner, Vachon and Tamimi2011). However, there are no special recommendations or screening guidelines for women with dense breast tissue, and insurance generally does not cover more sensitive follow-up tests such as ultrasound or MRI. Women have the option of paying for more sensitive tests themselves.

(iii) PGx is not the only factor influencing outcomes

While PGx testing may indicate a drug is safe or suitable for a patient, factors other than genetic polymorphisms have a significant effect on drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Epigenetic factors reveal a molecular basis for how information other than DNA sequence influences gene expression and can include epistatic interactions (Heil, Reference Heil2013), patient age and gender, concomitant drug use and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, diet), which can all impact the results of therapy. Payers may be reluctant to provide coverage for a PGx test if these factors are not adequately addressed or controlled for. Therefore the integration of epigenetic, lifestyle and genetic influences are needed in order to interpret utility of PGx testing and to allow for adoption into current treatment practices and payer reimbursement. The specific data points of interest vary between payers and are still evolving, however, which adds to the challenges and research complexity. Efforts underway to address various aspects of these needs include the National Cancer Institute (NCI) program on the role of both pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacogenomics in treatment responses and adverse outcomes for oncology drugs (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Sansbury, Figg, Potosky, Weiss Smith, Khoury, Nelson, Weinshilboum, Ratain, McLeod, Epstein, Ginsburg, Schilsky, Liu, Flockhart, Ulrich, Davis, Lesko, Zineh, Randhawa, Ambrosone, Relling, Rothman, Xie, Spitz, Ballard-Barbash, Doroshow and Minasian2010) and Reaction Biology Corporation, which is creating a database of epigenetic drug interactions with a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NIH, 2014).

(iv) Ethical and social issues

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act established in 2008 (NIH, 2015) is designed to protect individuals from discrimination based on genetic information. Ethical and social implications of genetic testing generally do not distinguish between PGx-guided therapy and testing for disease susceptibility. Consent for PGx testing designed to individualize drug therapy may not need the same level of scrutiny and requirements as genetic testing for disease susceptibility; however, as PGx testing continues to evolve, new research programs will emerge, such as the grant-backed NCI program addressing the ethical, legal, social and data-sharing implications of PGx and pharmacoepidemiologic research (NCI, 2014). A lessening in regulation and consent requirements for PGx testing might facilitate implementation as long as privacy and confidentiality are ensured for employment and payer coverage decisions (Dressler & Terry, Reference Dressler and Terry2009). This is an issue without current consensus.

(v) Adoption of new technologies and standards

The factors and considerations previously discussed are important prerequisites for adoption of testing in the absence of a regulatory or legislative mandate. An additional, important consideration is the real and perceived complexity of PGx testing, including integration into existing workflows, interpretation of results and availability of information at the point of care. Research and prior examples have demonstrated that technologies such as PGx, which are complex and highly networked, are adopted more slowly. In sum, not only must the test be accurate, but it must be easy to use and access relative to the clinical problem at hand. Additional considerations include advances in technology that include Big Data initiatives such as the 100,000 Genomes Project and ‘Precision Medicine Intitiative’ that may play a role in genetic data management and interpretation, and ultimately impact stakeholder acceptance and utilization of PGx information.

6. Summary and conclusions

The adoption of PGx-guided therapy faces commercial, economic, educational and ethical barriers to integration into clinical practice and acceptance by practitioners, patients and payers. Acceptance of PGx testing varies considerably by therapeutic area. In some areas, such as oncology and cardiovascular disease, PGx testing is already utilized for selecting appropriate patients and/or establishing treatment and dosing guidelines, while in other areas such as antiplatelet therapy, the PGx approach has been mainly used for the identification, validation and development of new meaningful biomarkers, and is considered experimental by most stakeholders. The acceleration of adoption of precision medicine in general, and for PGx testing in particular, will be determined by how quickly robust evidence can be accumulated that shows a return on investment for payers in terms of real dollars, for clinicians in terms of patient clinical responses, and for patients in terms of economic, health and quality of life outcomes.

The authors acknowledge Patrice C. Ferriola, PhD (KZE PharmAssociates, LLC) for assistance with writing this manuscript. Dr Ferriola's work was funded by Symphony Health Solutions. In addition, the authors acknowledge and appreciate the review and comments by Anthony Bower, PhD.

Declaration of interest

None.