No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

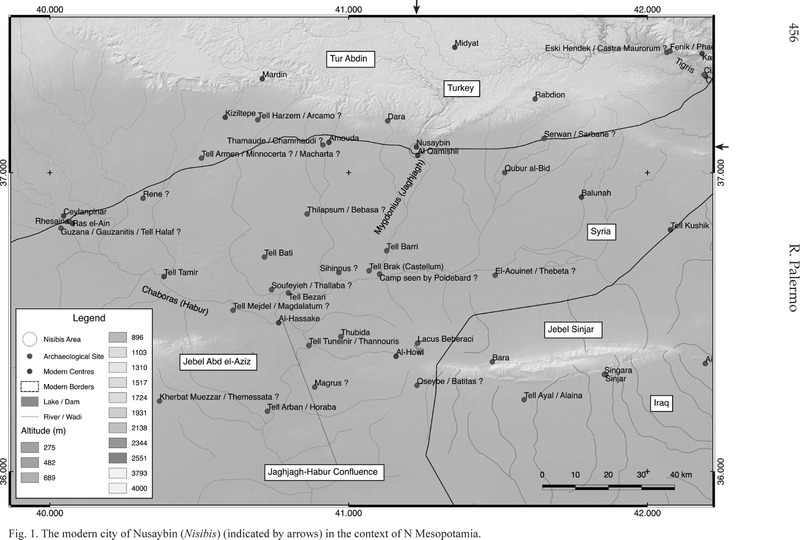

Nisibis, capital of the province of Mesopotamia: some historical and archaeological perspectives

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 November 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Archaeological Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Journal of Roman Archaeology L.L.C. 2014

References

1 In the early 1930s A. Poidebard studied the city. In La trace de Rome dans le désert de Syrie (Paris 1934)Google Scholar, there is an aerial photograph of Qamishli (built during this period) with, in the background, the Turkish city of Nusaybin. He stresses that this was the site of the ancient city, but also complains about the lack of any archaeological remains due to the presence of the two modern centres. Nisibis is also mentioned by Dillemann, L. (Haute-Mesopotamie orientale et territoires adjacents [Paris 1962])Google Scholar and Oates, D. (Studies in the ancient history of northern Iraq [Oxford 1968])Google Scholar: both try to reconstruct the layout of the Roman presence and the position of the limes in the area. In 1988, Lightfoot, C. (“Fact and fiction — the third siege of Nisibis AD 350,” Historia 37, 105–25)Google Scholar made a new study of Nisibis, focusing on that siege and references to it in 4th-c. sources. Recent discussions concerning the city appear in Russell, P. S., “Nisibis as the background to the Life of Ephrem the Syrian,” in Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 8 (2005) 179–235 (http://syrcom.cua.edu/hugoye/Vol8No2/HV8N2Russell.html)Google Scholar and Lieu, S., s.v. “Nisibis,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica (Winona Lake, IN 2006) (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nisibis-city-in-northern-mesopotamia)Google Scholar. Recent archaeological excavations are also trying to shed more light on the ancient city (see below).

2 Strab. 11.13.

3 Plin., , NH 31.37 and 33.16Google Scholar. The river's location is the subject of a debate between scholars. Russell (supra n.1) 187 states that the Jaghjagh did not pass through the city but to one side, quite close to the eastern city walls, as Lightfoot (supra n.1) 110 had said. Theodoret, (HE 2.26, ed. Parmentier, [1911])Google Scholar says that during the Sassanian siege the waters of the river were diverted to destroy the city walls, which seems to confirm that the river itself ran outside the circuit. Some Arabic sources (see Strange, G. Le, The lands of the eastern Caliphate: Mesopotamia, Persia, and central Asia, from the Moslem conquest to the time of Timur [Cambridge 1905] 94–95)Google Scholar and early European travellers (above all, Otter, Jean, Voyage en Turquie et Perse [Paris 1748] 121)Google Scholar confirm that the river, coming from north, passed close to the city but did not run through the middle. See also a passage in Ephrem’s Carmina Nisibena: “(the river) flows close to the city”. Zonaras 13.7 (vol. 3, p. 194 11. 7 and 13 [ed. L. Dindorf; 1870]), however, describes the river as flowing through the city, but probably by his day a suburb had developed, and the suburb was separated by the Jaghjagh itself (cf. Lightfoot [supra n.1] 111). In the aerial photographs taken during the French Mandate, the river is seen just to the east of the modern town of Nusaybin.

4 The annual rainfall ranges from 350 to 400 mm in the area of Nusaybin: Wilkinson, T. J., “Structure and dynamics of dry-farming states in Upper Mesopotamia,” Curr. Anthr. 35 (1994) 483–520 especially 484CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Ur, J. A., Urbanism and cultural landscapes in northeastern Syria: the Tell Hamoukar Survey, 1999-2001 (Chicago 2010) 10 Google Scholar.

5 Rossi, F. Canali De, Iscrizioni dello Estremo Oriente greco. Un repertorio (IGSK 65, 2004) p. 3 Google Scholar. The inscription seems to be lost.

6 Sturm, J., “Nisibis,” in P.-W., RE vol. 33 (1936) col. 727Google Scholar; Dillemann (supra n.1) 78 and n.2; Sherk, R. K., The Roman Empire from Augustus to Hadrian. Translated documents (Cambridge 1988) 173–74CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Braund, D. (Rome and the friendly king: the character of the client kingship [London 1984] 48)Google Scholar says probably this was the tombstone of the prince Amazaspus, a member of the royal family of Iberia and an ally of Trajan during the campaigns of 115-116. The inscription recounts not only the death of the prince but also that his grave was at Nisibis. The finding of the stele at Rome may be explained by the transport of his body after the end of the Parthian wars.

7 Dio 68.26.1. Many scholars have studied and discussed how the Mesopotamian landscape and climate were different from those of today. It is commonly held that the climate became warmer in the first two centuries of the present era, but that it was still wetter and more humid than in more recent times. See also Wilkinson, T. J., Archaeological landscapes of the Near East (Tucson, AZ 2003) 14–17 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

8 The rôle in agriculture played by the canals of N Mesopotamia, especially during the Assyrian period, has been discussed by Oates (supra n.1) 49-52 and Raede, J., “Studies in Assyriangeography, Part I: Sennacherib and the waters of Nineveh,” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie orientale 72 (1978) 47-72 and 157–80Google Scholar, and more recently by Ur (supra n.4).

9 In 1841, however, Southgate, H. (Narratives of a visit to the Syrian (Jacobite) Church of Mesopotamia [New York 1844] 119)Google Scholar described the poor health of the inhabitants and the rubbish to be seen everywhere in Nusaybin.

10 The city is mentioned with respect to “117 persons under H[…]nu from Nasipina”. Postgate, N. (“The Assyrian army at Zamua,” Iraq 62 [2000] 101–2)CrossRefGoogle Scholar suggested that the tablet listed different groups with Aramaean origins enrolled in the army of Aššur-nāṣir-apli. The missing name before Nasipina is thought to be Habinu. The name could possibly indicate an Aramaean tribe settled in Upper Mesopotamia. For Aramaeans in the Nisibis region, see especially Lipinski, J., The Aramaeans: their ancient history, culture, religion [Leuven 2000])Google Scholar.

11 At Josephus, AntJ 18.311-12, the city is said to be one of the places where the temple tax was collected. Here it is said to be on the Euphrates (like Nehardea, another tax centre), but recently A. Oppenheimer (“Nehardea und Nisibis bei Josephus [Ant. XVIII],” in Between Rome and Babylon: studies in Jewish leadership and society [Tübingen 2005] 418) has suggested that there is little evidence that the passage refers to Nisibis in Mesopotamia rather than another settlement to the south. On the Jewish diaspora in Upper Mesopotamia, and its relations with Parthia and Rome, see Sartre, M., D’Alexandre à Zénobie [Paris 2001] 932–48)Google Scholar. On the Jews at Nisibis during Trajan’s Parthian war, see Pucci, M., “Traiano, la Mesopotamia e gli Ebrei,” Aegyptus 59 (1979) 168–89Google Scholar. In the Midrash (Samuel 10.3) it is also said that Nisibis was an important centre for the silk trade and functioned as a base for Jewish merchants: cf. Young, G. K., Rome’s eastern trade: international commerce and imperial policy 31 BC–AD 305 (London 2001) 170–71Google Scholar. On the Jews and their integration at Nisibis in the 4th c., see Russell (supra n.1) 29-60.

12 Philostratus (Vit. Apoll. 1.20) mentions scattered villages mostly settled by Arabs. The Elder Pliny (NH 6.30) also mentions scattered villages (vicatim). Ammianus (14.8.6) records that the Seleucid foundations in Mesopotamia changed the previous pattern of scattered villages. Nikanor probably wished to control N Syria after the battle of Ipsos, to secure the area between the East and the Tetrapolis region: Capdetrey, L., Le pouvoir séleucide: territoire, administration, finances d’un royaume hellénistique (312-129 av. J.-C.) (Rennes 2007) 75 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

13 App., Syr. 57; Euseb., Chron. 1.116-17 (ed. Schoene).

14 Sartre (supra n. 11) 130-41. It is also possible that Seleucus established a small colony on the site, but the name Antiochia in Mygdonia must have been added later (Capdetry [supra n.12] 74 and n.139; also Primo, A., “Le surnom Nikanor de Séleucos I. Observations sur la fondation de Doura-Europos et d'Antioche de Mygdonie,” AntCl 80 [2011] 1)Google Scholar. As emphasized by Capdetry (73), the foundations in Mesopotamia during the Seleucid period were all katoikiai (e.g., Zeugma and Jebel Khalid). The Macedonian presence did not leave much of a mark on the local cultures, as seems to be shown by the return to earlier place-names after the end of Seleucid domination in the region. The case of *na-si-pi-na/Antiochia/Nisibis illustrates this: the change of name from Nisibis to Antiochia in Mygdonia occurred probably during the reign of Seleucus I ( Bousdroukis, A., “Les noms des colonies séleucides au Proche-Orient,” Topoi Suppl. 4 [2003] 12–13, and n.10)Google Scholar.

15 Strabo (16.1.23) mentions Mygdonia as the largest area in Mesopotamia. Otherwise, only an inscription from Delos (dated to the time of Demetrios I or III) mentions the existence of Mygdonia (IDelos XV 1.2). The adoption of the Macedonian name could be connected with the institution of a Seleucid district in this region in the first half of the 3rd c. B.C.: Capdetrey (supra n.12) 251. Plutarch (Luc. 32.6), on the other hand, indicates a Spartan origin for the soldiers settled at Nisibis after the Seleucid conquest.

16 This theory is based on a sentence by the anonymous author of the Chronicon of Khuzestan (I. Guidi [ed. and transl.], Chronicon Anonymum [CSCO, 1/2 scr. syr. 1/2] 15/39-15/32 [Paris 1903]), as proposed by N. Pigulevskaja, Les villes de l’état iranien aux époques parthe et sassanide [Paris 1963] 49-59, and Russell ([supra n.1] 12).

17 At Pliny, NH 6.26, Nicanor, governor of Mesopotamia, is given as the founder of a settlement called Antiochia Mygdoniae (he is said to be a dux Mesopotamiae). On “Nicanor” the founder of cities, see especially Primo (supra n.14). The interpretation proposed by Primo in relation to the double use of Nikanor and Nikator for Seleucus I seems poorly supported with respect to the dynamics underlying the foundation of Dura. The passage of Pliny appears to be contradicted by CIG IV 6856, which reads “[…] beyond the holy cities, built by Nicator[…]”. Nicator was the Seleucus I who probably founded (or symbolically re-founded) the city in c.302 B.C. V. Tscherikower (Hellenistischen Stadtegrundungen von Alexander dem Grossen bis auf die Römerzeit [Leipzig 1927] 80) suggested that Pliny’s Antiochia Arabis could be identified with Nisibis, so named before the reign of Antiochus IV. Dillemann ([supra n.1] 78) endorsed Pliny, saying that Antiochia Arabis could be Costantina (Viranşehir). Lieu ([supra n.1] 2) has suggested that Nisibis’ change of name could have occurred during a later re-foundation under Antiochus IV; see also Capdetry (supra n.12) 74.

18 Dio 36.6.2.

19 K. Kessler, Der neue Pauly Bd. 8 (2000) 962, s.v. Nisibis.

20 Plut., Luc. 32.4; Dio 36.6-8. A short Roman occupation at this time seems widely accepted: Sturm, J., “Nisibis,” in P.-W., RE 33 (1936) 730)Google Scholar and Pigulevskaja (supra n.16) 49-59.

21 A high population in the region might have been the reason for so large a coin issue, but perhaps coins struck at Nisibis served the broader Middle Euphrates region: cf. Aperghis, G. G., The Seleukid royal economy (Cambridge 2004) 219 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Bikerman, E., Institutions des Séleucides (Paris 1938) 214 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. It is interesting to note the presence of gold coins at Nisibis during the reign of Antiochos III (the same occurs at Seleucia on the Tigris and Susa), which could be connected to the salaries of soldiers in the region. The riches probably came from the sack of the temple of Aines (Polyb. 10.27.13), but they may also be an indication of the new commercial appeal of the whole Mesopotamian region.

22 Edwell, P., Between Rome and Persia: the Middle Euphates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman control (London 2008) 12 Google Scholar. Nisibis became a city in the kingdom of Adiabene, a vassal state of the Parthian empire, along with others such as Hatra and Singara: Lightfoot (supra n.1) 118.

23 The lack of any mention of Nisibis in these events is probably explained by the secondary rôle played by the whole Mesopotamian plateau in Corbulo’s campaigns, which focused mainly on Armenia and the Upper Taurus.

24 Dio 68.17.1-3. According to him (68.18.3), at the end of the military operations only the three large cities of the region (Edessa, Nisibis, less probably Hatra) were in Roman hands, while the rest of the area was not well under Roman control. The town of Adenystrae (not yet located: cf. Gregory, S. and Kennedy, D., Sir Aurel Stein's limes report [BAR S272, Oxford 1985] 399)Google Scholar was also conquered by the army of Lusius Quietus: Dio 68.22.

25 Eutrop. 8.3 and 8.6; Fest. 14 and 20. Both authors speak about the provinces of Assyria, Armenia and Mesopotamia. According to Dillemann (supra n.1) 117 and Angeli Bertinelli (“I Romani oltre l’Eufrate: le province di Assiria, Mesopotamia e Osroene nel II sec.d.C.,” in ANRW 9.1 [1978] 20), it is hard to determine the organization and socio-political aspects of the newly acquired territories. See also Lightfoot, C., “Provincie romane, Assyria,” in Enciclopedia dell’Arte Antica, Classica e Orientale 2nd suppl. 1971–1994, vol. IV (1996) 643–45Google Scholar.

26 It is now lost. The “great amount of Roman pottery” mentioned by Lightfoot, C. S. (“Trajan's Parthian War and the fourth century perspective,” JRS 80 [1990] 123–24)Google Scholar as evidence of a “real” Roman presence in the area needs to be re-evaluated. The local nature of the pottery from the excavated sites, alongside with a few pieces of genuine “Roman” pottery, should probably be taken as an indication of rather light control by Roman troops.

27 According to a passage in Lucian (Hist. Conscr. 15), Nisibis was affected by a terrible plague during the siege. For the campaigns of Lucius Verus in general, see Millar, F. G. B., The Roman Near East (31 BC-AD 337) (Cambridge, MA 1993) 111–14Google Scholar.

28 Millar ibid. 114. The troops were probably used to patrol the area and the road leading from Edessa to the Tigris via Singara. The theories were endorsed by Butcher, K. (Roman Syria and the Near East [London 2003] 48)Google Scholar and Edwell ([supra n.22] 24).

29 Dio 75.6-1-3; SHA, Sev. 15.2-3; also Southern, P., The Roman army: a social and constitutional history (Oxford 2007) 319 Google Scholar. The presence of Osrhoeni and Adiabaeni suggests, according to Ross, K. (Roman Edessa [London 2001] 47)Google Scholar, that those peoples supported Pescennius Niger, while Nisibis and its population backed Septimius Severus.

30 Nisibis is said to be “Roman” at the end of the 3rd c. A.D. Rhesaina (mod. Ras el-Ain) and probably Singara (mod. Sinjar) were also made coloniae: Septimia Rhesaina and Aurelia Septimia Singara. On the creation of Roman colonies during the Severan period in Mesopotamia, see Oates (supra n.1) 62-68; Millar, F. G. B., “The Roman coloniae of the Near East: a study of cultural relations,” in Solin, H. and Kajava, M., Roman eastern policy and other studies in Roman history (Helsinki 1990) 38–39 Google Scholar; Millar (supra n.27) 124-26; Pollard, N., Soldiers, cities and civilians in Roman Syria (Ann Arbor, MI 2000) 120–22CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Edwell (supra n.22) 24-26. Several later coins bear the legend CEP. KOL. NECIBH (BMC 4), with MHT (= metropolis) added after Philip’s reign (BMC 21).

31 Legio I Parthica was initially stationed at Singara, while II Parthica was at Albanum (Italy) and III Parthica at Rhesaina: Edwell (supra n.22) 28. All three legions were probably created before the departure from Rome and specifically for this war (perhaps one for the first campaign, the others for the next). According to D. L. Kennedy (“The garrisoning of Mesopotamia in the late Antonine and early Severan period,” Antichthon 21 [1987] 59), the legions were probably created between the first and second campaigns and were stationed there to patrol the newly conquered territories, but it is more likely that the legions were created by Septimius Severus before the campaigns in order to achieve a rapid victory (Edwell [supra n.22] 216 with n.122). The presence of two legions in so small a region should be seen as further evidence of Rome's will to take and retain control of a strategic area. An inscription recently found in Turkey seems to refer to a soldier of II Parthica: Stauner, K., “New inscriptions from soldiers of the Roman army,” Gephyra 9 (2012) 86–91 Google Scholar.

32 Feissel, D., Gascou, J. and Teixidor, J. (“Documents d’archives inédits romains du Moyen Euphrate (IIIe s. après J.-C.),” JSav 1997.1, 41)Google Scholar have suggested that the centurion probably retired to Nisibis after having been stationed at Singara. It is also possible that at least a part of the legion was moved to Nisibis from Singara. The presence of the legion at Singara is recorded on an undated inscription from Aphrodisias ( BCH 9 [1885] 81 Google Scholar = Dessau 9477; cf. Amm. Marc. 20.6.8).

33 The appellative Antoniniana is a further clue for the chronology of the legion. It must have been created by the emperor before 211. The Notitia mentions the epithet Nisibena, probably in relation to the strong defence of the city during the three 4th-c. sieges: cf. Lightfoot (supra n.26) 109.

34 Dio 74.26. He says that the early skirmishes were due to water problems. The passage could support the argument that the river was outside the city.

35 Zonaras 12.15. K. Butcher (supra n.28) 51 proposes that this occurred in A.D. 224 on the basis of a relief in Firuzabad in which Persian horsemen are recognizable leading in chains their Arsacid enemies.

36 Nisibis does not appear in the list of cities conquered during the second and third campaign of Shapur I, present on the Shapur Kaba Zartusht, the inscription of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rustam in Fars: see transl. Frye, R. N., The history of ancient Iran (Handbuch der Altertumwissenschaft, 3. Abt., T. 7, App. 4 [1983])Google Scholar.

37 SHA, Gall. 10.3 and 12.

38 The 4th-c. Expositio totius mundi et gentium (22) records that Nisibis was known, along with Edessa, for being inhabited by the richest businessmen and individuals.

39 The most important is the still-standing baptistery in Nusaybin. Greatly modified over the centuries, it houses the tomb of St. Jacob. The early construction phase belongs in A.D. 359 under the guidance of Bishop Vologaeses; it was modified twice, in the 7th and at the end of the 18th c. The baptistery had a rectangular main structure and a pyramidal roof. A reconstruction in A. Khatchatrian, “Le baptistère de Nisibis,” StAntCrist 22 (1957) 407-21, shows how the main building was surrounded by a pronaos with columns. Nowadays the structure is partially enclosed in other religious buildings of Nusaybin's historic centre.

40 The walls are described as a double curtain system, although the inner wall was less efficacious than the outer one. Dio (35.7) and Ammianus (25.8.14 and 25.9.1) both describe the massive walls. The latter also refers to an arx where a flag was placed after the conquest of the city in 363.

41 McEwan, C. et al., Soundings at Tell Fakharyia (Chicago 1957)Google Scholar.

42 Oates (supra n.1) 98-106.

43 Ammianus (20.6.3-7) refers to the wall of Singara as having been destroyed by battering-rams during the siege of 360.

44 The evolution from this kind of fort toward the medieval caravanserai was quite rapid in the Near East: Parker, S. T., The Roman frontier in central Jordan. Final report on the Limes Arabicus Project 1980-1989 (Washington, DC 2006) 209–11Google Scholar. According to Parker, the structures date back to the Tetrarchic period and must have been influenced by city fortifications or Parthian/Persian work in stone.

45 Bell, G. L., The churches and monasteries of Tur ‘Abdin (London 1982) pl. 69Google Scholar.

46 Kinneir, J. M., Journey through Asia Minor, Armenia and Koordistan in 1813 and 1814 (London 1818) 443 Google Scholar.

47 See also Dillemann (supra n.1) 81-82.

48 On the Arch see in general Brilliant, R., The Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum (MemAmAc 29, 1967)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. On the religious life of Nisibis, see also Haider, P. W., “Tradition and change in the beliefs at Assur, Nineveh and Nisibis between 300 BC and AD 300,” in Kaizer, T. (ed.), The variety of local religious life in the Near East (Leiden 2009) 193–207 Google Scholar.

49 Dillemann (supra n.1) 80 reports that some broken sarcophagi with other associated material were found on this hill.

50 Parrot, A., “Les fouilles de Mari. Cinquième campagne (automne 1937), rapport préliminaire,” Syria 20 (1939) 21–22 CrossRefGoogle Scholar (photograph showing three sides on p. 20).

51 Seyrig, H., “Le trésor monétaire de Nisibe,” RNum 5, ser. 17 (1955) 85–128 Google Scholar.

52 Dillemann (supra n.1) pl. 8.

53 Gatier, P.-L., “Inscriptions latines et reliefs du Nord de la Syrie,” in Syria 65 (1988) 227–29CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

54 CIL XIII, 8033; see also Alföldy, G. in Epigraphische Studien 6 (1988) 220 Google Scholar.

55 Fiey, J. M., Nisibe, métropole syriaque orientale et ses suffragants des origines à nos jours (Louvain 1977) 23 Google Scholar.

56 Sarre, F. P. T. and Herzfeld, E., Archäologische Reise im Euphrat und Tigris Gebiet (Berlin 1911) vol. 2, 341 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Khatchatrian (supra n.39) 407-21; Castelfranchi, M. Falla, Baptisteria. Intorno ai più noti battisteri dell’Oriente (Rome 1980)Google Scholar, and ead., “Battisteri e pellegrinaggi,” in Dassmann, E. and Engemann, J. (edd.), Akten des XII Int. Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie (Münster 1995) 234–48Google Scholar.

57 Sarre and Herzfeld ibid. 337.

58 Keser-Kayaap, E. and Erdogan, N., “The cathedral complex at Nisibis,” AnatSt 63 (2013) 137–54Google Scholar. Gaborit, J., Thébault, G. and Oruç, A., “Mar Ya‘qub de Nisibe,” in Briquel-Chatonnet, F. (ed.), Les églises en monde syriaque (Études Syriaques 10, 2014)Google Scholar. For an overview of the architectural remains of this general area, see also M. M. Mango (supra n.45) 97-173; ead., “The continuity of the classical tradition in the art and architecture of northern Mesopotamia,” in Garsoian, N. G., Mathews, T. F. and Thomson, R. W. (edd.), East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the formative period (Washington, D.C. 1982) 47–70 Google Scholar; Sinclair, T., Eastern Turkey: an architectural and archaeological survey (London 1987)Google Scholar.

59 CORONA images are part of a now-declassified US government project developed between 1959 and 1972. On the use of these images in archaeological contexts, see Ur, J. A., “CORONA satellite photography and ancient road networks: a northern Mesopotamian case,” Antiquity 77 (2003) 102–15CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 Keser-Kayaalp, E. and Erdogan, N. “The cathedral complex at Nisibis,” AnatSt 63 (2013) 138 Google Scholar.