Standard Tajik, or Modern Literary Tajik as it was called during the Soviet era, was established in the nineteen twenties and thirties based largely on the dialects of the Bukhara-Samarkand area, which was at the time the undisputed cultural centre of the Tajik-speaking population. Dushanbe, the current capital of Tajikistan, was then a small village with a population of only a few hundred and had no cultural heritage comparable to that of Bukhara or Samarkand.Footnote 1 Bukharan Tajik, whose phonology is described in this paper, is a variety of Tajik that played a particularly influential role in the phonological standardization of Tajik, which took place for the most part in 1930. For instance, the Scientific Conference of Uzbekistan Tajiks of 1930 resolved that the dialect of Bukhara must be the designated basis of the sound and orthography of literary Tajik (вaroji tajjorī вa kanfiransijaji ilmiji istalinoвod 1930: 2). In August the same year, the Linguistic Conference held in the then newly established Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic also adopted a similar resolution that establishes the ‘language of the Tajiks of Samarkand and Bukhara’ as the reference point in establishing the literary (i.e. standard) pronunciation (Halimov Reference Halimov1974: 126). According to Bergne (Reference Bergne2007: 82), ‘the same Linguistic Conference of 22 August 1930 in Stalinabad decided that the phonetic base for the language had better be the dialect of Bukhara’.Footnote 2 , Footnote 3 Thus, the Bukharan Tajik of today is the direct descendant of the variety of Tajik which served as a primary basis of standard Tajik phonological norms; and hence differs little from standard Tajik phonologically and phonetically.

The resolutions mentioned above were passed at the respective conferences despite the fact that both Bukhara and Samarkand were within the territory of Uzbekistan, in which they would remain to the present day. This has resulted in an interesting phonological discordance between standard Tajik and many dialects spoken in Tajikistan. Bukharan Tajik and the dialect of Samarkand belong to the Northern dialects, which share basically the same phoneme inventory. Since standard Tajik is based on the dialects of the Bukhara-Samarkand area, its phoneme inventory is also basically that of the Northern dialects. On the other hand, Dushanbe is just outside the area where the Northern dialects are spoken, and as a result, the phoneme inventory of the dialects spoken in the area where the capital city is situated does not coincide with that of standard Tajik. For example, the Northern dialects, and hence also standard Tajik, have the phoneme /ɵ/, but the close-mid central vowel is either an unstable phoneme or not a phoneme at all in the dialects spoken in the area where Dushanbe is situated. (A dialect in which the merger of /ɵ/ and /u/ has been recorded is spoken in a village located nine kilometres north of Dushanbe, suggesting the southern limit of the Northern dialects is further north.)Footnote 4 The phoneme inventory of the Northern dialects does not coincide with that of the dialects spoken by the people who have dominated Tajik political life after the civil war (1992–1997) either, because they are speakers of the Southern dialects.Footnote 5

Despite its status as a basis of standard Tajik, Bukharan Tajik survives today primarily as a spoken variety with no standardized writing system. This is due, at least partly, to the political isolation of Bukhara from Tajikistan and to the fact that only a small fraction of Tajik speakers in Bukhara receive education in or on the standardized Tajik of Tajikistan. Bukhara is situated in the western-most corner of the Tajik-speaking area with another sizeable concentration of the Tajik-speaking population more than two hundred kilometres away and Tajikistan even further. The standardized Tajik of Tajikistan has a very limited presence in Bukhara, in which the language of administration, officialdom, education, and publication is now firmly Uzbek, with Russian making up a decreasing share of it. Many Bukharan Tajik speakers appear to have little desire to acquire the standardized Tajik of Tajikistan though they typically acknowledge its prestige by attaching to it such positive attributes as ‘pure’ (i.e. not heavily ‘Uzbekified’) and ‘proper’.

Today the use of Bukharan Tajik is limited to everyday interpersonal communication. In formal registers, Bukharan Tajik speakers usually resort to using a language in which they have written proficiency, namely Uzbek. Since Bukharan Tajik is a spoken variety without a written norm, written Bukharan Tajik is confined to private spheres, such as personal correspondence, shopping lists, and diaries, where Bukharans write in their respective idiolects (as there is neither an orthography nor a standardized grammar shared among Bukharan Tajik speakers).

Bukharan Tajik has diverged considerably from standard Tajik in its grammar and lexicon. The Tajik language of the media in Tajikistan is decreasingly intelligible to average Bukharan Tajik speakers, who have replaced a number of basic lexical items of Tajik (e.g. the words for ‘cloud’, ‘eyebrow’, and ‘to wait’) with their Uzbek and Russian counterparts and who have no knowledge of some of the grammatical constructions that are in frequent use in the Tajik media. For example, deontic modality marking with бояд ‘must’, future tense marking with хостан ‘want; will’, and superlative degree marking with ‑тарин, all of which have much currency in standard Tajik, are unknown to the average speaker of Bukharan Tajik. Not surprisingly, such lack of grammatical knowledge has a significantly adverse effect on the intelligibility of standard Tajik by Bukharan Tajik speakers.

Virtually every Bukharan Tajik speaker is bilingual in Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek, the Turkic language with which Tajik has been in intensive contact for centuries.Footnote 6 Language mixing, i.e. code switching and code mixing (Ritchie & Bhatia Reference Ritchie, Bhatia, Bhatia and Ritchie2004: 336–337), takes place even in households where every member is a native speaker of Bukharan Tajik. However, Bukharan Tajik–Uzbek bilingualism is not limited to those who have Bukharan Tajik as their first language – native Uzbek speakers who grow up in the city of Bukhara usually acquire some command of Bukharan Tajik, which they use either passively or actively. It may also be worth noting that Bukharan Tajik enjoys some prestige in Bukhara province as the language of city dwellers.

The formant data of Bukharan Tajik vowels that appear in this paper come mostly from two informants. One of them, to whom most of the recorded voices accompanying this paper also belong, is a female native Bukharan Tajik speaker in her early twenties. The other informant is a male native Bukharan Tajik speaker in his mid-twenties. The informants, both of whom are bilingual in Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek, will be referred to in this paper simply as ‘the female informant’ and ‘the male informant’, respectively.

Bukharan Tajik and Persian

Tajik is closely related to Dari and to Persian within the western subgroup of the Iranian languages. Tajik is officially called забони тоҷикӣ ‘the Tajik language’ in the Republic of Tajikistan, but it has been frequently referred to as the Central Asian dialect of Persian (Halimov Reference Halimov1974: 30–31). Today, whether one regards Tajik as a language distinct from Persian or as a variety of it depends more on sentiment and politics than it does on science.Footnote 7 The stance of the government of Tajikistan on this issue too has swung around in the past. In the language law of the Tajik SSR adopted on 22 July 1989, the word форсӣ ‘Persian’ in brackets was added to the term забони тоҷикӣ ‘the Tajik language’ only to be removed later when the law was revised in 1992 (Tojnews 2009).

However, regardless of the linguistic unity of Tajik and Persian or lack thereof, Bukharan Tajik arguably merits a separate name from the Persian of Iran, because the mutual intelligibility between Bukharan Tajik and Persian appears to be confined to grammatically and lexically simple utterances. None of the following morphemes and words, all of which are present in the ‘North Wind and the Sun’ passage at the end of this paper, exists in Persian: the ablative case suffix /ban/, dative suffix /ba/, postposition /kati/ ‘with’, noun-forming suffix /ʨi/ ‘-er, -ist’ (< Uzbek suffix -chi), Russian loanwords /spoɾ/ ‘argue’ (< Russian noun спор), /kansakansof/ ‘eventually’ (< Russian phrase в конце концов), /atkazat/ ‘give up’ (< Russian verb отказать(ся)), /sɾazu/ ‘straightaway’ (< Russian adverb сразу), Uzbek loanwords /kuʨ/ ‘strength’ (< Uzbek noun kuch), /keliɕmiɕ/ ‘agree on’ (< Uzbek participle kelishmish), and /iɕqilib/ ‘in short, to sum up’ (< Uzbek adverb ishqilib). A few dozen Bukharan Tajik auxiliary verbs, e.g. /mondan/ ‘to stay’ in /dida mondan/ ‘suddenly saw’, are also foreign to Persian. The prenominal relative clause, two instances of which are found in the following sentence taken from the ‘North Wind and the Sun’ passage, is no less foreign to Persian:

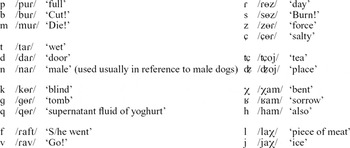

Consonants

/t/ and /d/ are articulated at both the upper teeth and alveolar and hence are denti-alveolar.

The consonants in the column for postalveolars are in fact alveolo-palatals. The number of native words in which /ʑ/ occurs is small in Tajik in general, and is even smaller in Bukharan Tajik, hence the brackets. The female informant recalls only the following six words as native Bukharan Tajik words in which /ʑ/ occurs: /laʁʑidan/ ‘to slip’, /aʑdaχo/ ‘dragon’, /aʑdaɾ/ ‘dragon’, /ʁiʑʑak/ ‘a kind of stringed musical instrument’, /ʁaʑʁuʑ/ ‘the sound of wood sawing’, /ʁiʑʁiʑ/ ‘the sound of wood sawing’.Footnote 8 She does not recall any native Bukharan Tajik words with word-initial /ʑ/, which is nevertheless abundant in her loanword vocabulary. Commonly used loanwords with word-initial /ʑ/ include /ʑdat/ < Russian ждать ‘to wait’, which is used in the light verb construction /ʑdat kaɾdan/ ‘to wait’ and /ʑaɾit/ < Russian жарить ‘to fry’, which is also used in the light verb construction /ʑaɾit kaɾdan/ ‘to fry’.Footnote 9 A number of words with /ʑ/ in Tajik have /ʥ/ in their Bukharan Tajik counterpartsFootnote 10 (for example, Tajik мижа /miʑa/ ‘eyelash’ corresponds to Bukharan Tajik /midʥa/Footnote 11 ), which partly explains why the occurence of /ʑ/ in Bukharan Tajik is largely confined to the loanword vocabulary. /ʁiʑʁiʑ/ ‘the sound of sawing wood’ and /ʁiʨʁiʨ/ ‘a sound symbolic word denoting crowdedness’ are one of few minimal pairs in the native Bukharan Tajik lexicon that involve /ʑ/.

Buzurgzoda (Reference Buzurgzoda1940: 44) reports of Tajik dialects in which /f/ and /v/ are phonetically [ɸ] and [β], respectively, with the implication that the bilabial fricatives in the dialects are Uzbek and/or Kirghiz in origin. In contrast, Bukharan Tajik, which is also in intensive contact with Uzbek, does not utilize [ɸ] or [β]. However, the consonant phoneme inventory of Bukharan Tajik is broadly similar to that of Uzbek, with the former lacking the /ɸ/, /β/, and /ŋ/ of Uzbek and the latter lacking the /f/ and /v/ of Bukharan Tajik.

The pharyngeal fricatives that have been reported to exist in many Tajik dialects (Rastorgueva Reference Rastorgueva1964: 51–52, 166), including the dialect of Samarkand Jews (Ešniëzov Reference Ešniëzov1977: 65), are absent in Bukharan Tajik.

The word-initial vowel is regularly preceded by the glottal plosive, which, however, is not a phoneme in Bukharan Tajik.

The difference in voice onset time (VOT) between the voiced word-initial plosives /b d ɡ/ and their voiceless counterparts /p t k/ is large in the recordings of the above-listed words, with their VOTs ranging from approximately −80 to 20 milliseconds for the voiced plosives and from approximately 40 to 80 milliseconds for the voiceless plosives (which actually carry aspiration).

Vowels

The Bukharan Tajik vowel inventory consists of six phonemes, namely /i e a ө o u/. Figure 1 shows the formant frequencies of the vowels which the informants produced in the test words of /saχ/ ‘hard’, /se/ ‘three’, /si/ ‘thirty’, /soχt/ ‘s/he made’, /sөχt/ ‘s/he burnt’, and /suq/ ‘evil eye’. Unfortunately, the small size of the native lexicon that is shared among all Bukharan Tajik speakers meant that no native context was found in which every one of the six vowels could be placed, hence the different contexts (/sV/, /sVχ/, /sVχt/) of the test words. Two of these words, namely /se/ and /si/ were randomized along with thirteen other monosyllabic numerals to form four lists of words, which the informants read aloud. The other four test words were similarly randomized with twenty-three other native Bukharan Tajik words to form another four lists of words. Consequently, a total of four repetitions were recorded for each of the test words.Footnote 12

Figure 1 Mean F1 and F2 values of the Bukharan Tajik vowels in /sax/ ‘hard’, /se/ ‘three’, /si/ ‘thirty’, /soxt/ ‘s/he made’, /sext/ ‘s/he burnt’, and /suq/ ‘evil eye’ produced by the female informant (top) and the male informant (bottom).

The most noticeable allophonic variation observed in the vowel phonology of Bukharan Tajik is that of /i/, whose allophone [ɨ] occurs following and/or preceding a uvular consonant, e.g. in /ʁiʑʁiʑ/ (see the preceding section).

The reduction of /i/, /u/, and /a/ that has been repeatedly documented in the Tajik linguistic literature (e.g. in Sokolova Reference Sokolova1949: 32–33; Bobomurodov Reference Bobomurodov1978: 6–7; T. N. Xaskašev Reference Xaskašev1983: 89–91; T. Xaskašev Reference Xaskašev, Rustamov and Ǧafforov1985: 42) is also observed in Bukharan Tajik. In unstressed open syllables, /i/ and /u/, and to a lesser degree /a/, are more susceptible to vowel reduction than the other three vowels, namely /e/, /o/, and /ɵ/. Compare, for example, /beˈɾaχm/ ‘merciless’, in which the unstressed vowel /e/ is not reduced, with /biˈɾinʥ/ ‘rice’, where the unstressed /i/ is reduced/centralized to [ə] (Figure 2). The immunity of /e/, /o/, and /ɵ/ to radical reduction may possibly have some relation to the fact that they all descend from Early New Persian long vowels, while the other vowels, namely /a/, /i/, and /u/, descend either wholly or partly from Early New Persian short vowels (see Windfuhr Reference Windfuhr and Comrie1987: 457–458 for detail).

Figure 2 /beˈɾaχm/ ‘merciless’ (top) and /biˈɾinʥ/ ‘rice’ (bottom) produced by the female informant.

One peculiarity of the male informant's vowel system that differentiates it from the female informant's vowel system is the relative backness of the male informant's /ө/ (see Figure 1).Footnote 13 One may be tempted to identify the back realization of /ө/ in his vowel system as a characteristic of the vowel system of male Bukharan Tajik speakers in general. However, it is not clear whether this is the case, as the formant data obtained from a group of ten male Bukharan Tajik speakers (Figure 3) do not exhibit the same degree of /ө/-backness as those obtained from the male informant – in fact, formant data shown in Figure 3 appear to point to a vowel system of male Bukharan Tajik speakers where the six vowels are more evenly distributed in the vowel space.Footnote 14

Figure 3 Mean F1 and F2 values of the Bukharan Tajik vowels produced by nine female speakers (top) and ten male speakers (bottom).

It is also worth mentioning that the two plots in Figure 3 exemplify the ‘anatomically unexplained’ (Diehl et al. Reference Diehl, Lindblom, Hoemeke and Fahey1996: 188) formant similarities of the male and female close rounded back vowel which have attracted repeated attention among phoneticians (e.g. Fant Reference Fant1966, Simpson & Ericsdotter Reference Simpson and Ericsdotter2003).

Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek vowel systems

Since Bukharan Tajik speakers are bilingual in their native language and Uzbek, in the next few paragraphs, I attempt a preliminary comparison of the vowel systems of Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek as they are represented in the speech of the two Bukharan informants. Uzbek, like Bukharan Tajik, has six vowel phonemes.

Observe Figure 4, which shows the formant frequencies of the six Uzbek vowels as they were produced by the informants in the Uzbek test words uz ‘Tear off!’, ez ‘Crush!’, iz ‘trace’, oz ‘few’ o'z ‘self’, and az, the last of which is a meaningless word in Uzbek.Footnote 15

Figure 4 Mean F1 and F2 values of the Uzbek vowels in the /Vz/ context produced by the female informant (top) and the male informant (bottom).

A comparison of Figure 1 with Figure 4 reveals an interlingual consistency between the informants’ Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek vowel systems – their Bukharan Tajik vowels exhibit a marked resemblance to their Uzbek vowels in terms of their positions relative to one another in the F1-F2 space. The Bukharan Tajik vowels of the male informant in particular are virtually identical with his Uzbek vowels. Does this, then, mean that Uzbek happens to have a vowel system that is identical with that of Bukharan Tajik? The formant values of standard Uzbek vowels plotted in Figure 5 indicate that this is not the case – the vowel system of the Tashkent dialect of Uzbek, which is the phonetic basis of standard Uzbek, clearly differs from the Uzbek vowel systems of the Bukharan informants shown in Figure 4.Footnote 16

Figure 5 Mean F1 and F2 values of the Uzbek vowels produced in the /Vz/ context (top) and in isolation (bottom) by a male native Uzbek speaker (born 1985) from Tashkent.

In other words, the Bukharan informants’ Uzbek vowel systems have non-standard features that render them practically identical with the Bukharan Tajik vowel system. Two such non-standard features can be identified in their Uzbek vowel systems. One of them is the closeness of the vowel in oz ‘few’. The vowel in oz, which is open-mid in standard Uzbek, is close-mid in the Uzbek vowel systems of the Bukharan informants and thus coincides with Bukharan Tajik /o/. This observation is in agreement with Mirzaev's (1969: 19, 28, 30) remark that the vowel is very close to Tajik /o/ in the variety of Uzbek spoken by Bukharan Tajik-Uzbek bilinguals. The other feature is the frontness of the vowel in o'z ‘self’ relative to the back vowels in oz ‘few’ and uz ‘Tear off!’. While the vowel in o'z is a fully back vowel in standard Uzbek, it is more front in the Bukharan bilinguals’ Uzbek vowel systems, and coincides with Bukharan Tajik /ө/. This observation is endorsed by Bobomurodov's (1978: 13) remark that the Uzbek close-mid rounded vowel differs from Tajik close-mid rounded /ɵ/ in being a back vowel.

Thus, the closeness of the vowel in oz ‘few’ and the relative frontness of the vowel in o'z ‘self’ distinguish the Bukharan informants’ Uzbek vowel systems from the standard Uzbek vowel system. These are at the same time the features that render their Uzbek vowel systems practically identical with the Bukharan Tajik vowel system of /i e a ө o u/.

Interestingly, these two non-standard features are also found in the Uzbek vowel system of a native Uzbek speaker from Bukhara district (Figure 6). The male native Uzbek speaker has Uzbek as his first language and is bilingual in Bukharan Tajik.Footnote 17

Figure 6 Mean F1 and F2 values of the Uzbek vowels produced in isolation by a male native Uzbek speaker (born 1988) from Bukhara.

Thus, the three bilinguals from Bukhara, regardless of their first languages, utilize similar Uzbek vowel systems which are characterized by their resemblance to the Bukharan Tajik vowel system. This allows the speculation that Central Asian Iranian–Turkic language contact has reorganized the vowel systems of Tajik and Uzbek in the Bukhara area in such a way that they resemble each other. There are a few lines of evidence that seem to suggest that this is the case. I present some of this evidence below, though this is admittedly fragmentary, not least because no wide-scale study has been carried out in Bukhara that involves measurement of vowel formant frequencies.

One piece of evidence comes from Central Asian Arabic. According to Tsereteli (Reference Tsereteli1970), in the dialect of Arabic spoken in Bukhara province, a couple of vowel shifts occurred where ‘C[ommon] A[rabic] /ā/’ and ‘/aw/’ shifted to a position close to that of Tajik /o/ and the position of Tajik /ө/, respectively. If, as Tsereteli claims, the shifts took place due to Tajik influence, it shows that reorganization of a vowel system can and did occur in the Bukhara area. Perhaps more importantly, it shows that all of the Iranian, Turkic, and Semitic varieties in the Bukhara area have /ө/ as a phoneme (Bukharan Tajik /ө/, the non-back Uzbek vowel in o'z, and Central Asian Arabic /aw/ > /ө/). This is significant because /ө/ is not used in all (six-vowel) Uzbek dialects that are classified as belonging to the same dialect group as the Bukhara dialect, nor is it widespread among Tajik dialects.Footnote 18 , Footnote 19 The fact that /ө/ exists in genetically different languages in Bukhara appears to lend further support to the speculation that language contact shifted vowels in different languages in Bukhara, resulting in their utilization of vowel systems that resemble one another.

Another piece of evidence is the number of vowels in Tajik and Uzbek dialects. The number of vowel phonemes vary in Tajik and Uzbek dialects. Uzbek dialects with six vowel phonemes are most conspicuous in the Tajik-Uzbek contact area, with other dialects typically utilizing larger inventories of vowels (see Šoabdurahmonov Reference Šoabdurahmonov and Šoabdurahmonov1971: 397–398; Rešetov & Šoabdurahmonov Reference Rešetov and Šoabdurahmonov1978: 44–46; Rajabov Reference Rajabov1996: 99–100). The picture is pretty much the same for Tajik dialects, with six-vowel dialects distributed prominently in areas where Tajik-Uzbek bilingualism has been the norm (Rastorgueva Reference Rastorgueva1964: 31–41). This, together with the lack of vowel harmony in Uzbek six-vowel dialects, which has often been ascribed to Tajik/Iranian influence (e.g. Johanson Reference Johanson and Brown2006), may be seen as circumstantial evidence that language contact influenced the vowel systems of Tajik and Uzbek in bilingual areas (of which Bukhara is one) to be more like each other.

In sum, the two informants and an Uzbek speaker from Bukhara use similar Uzbek vowel systems, which are characterized by their resemblance to the Bukharan Tajik vowel system. This resemblance may be ascribed to the language contact in Bukhara, as evidence appears to suggest that the language contact induced Bukharan Tajik and Uzbek vowel systems to resemble one another.

Vowel length

Vowel length was a point of contention during the period of standardization of Tajik, when Tajik linguists were in disagreement as to whether the long vowels /iː/ and /uː/, which originate in Early New Persian, were to be credited the status of phonemes in standard Tajik. Indeed, the dialects on which standard Tajik is based were not homogeneous in their degree of retention of the historical vowel length distinction.Footnote 20 The Samarkand dialect has been explicitly classified as a dialect without /iː/ by Buzurgzoda (Reference Buzurgzoda1940: 33). Rastorgueva (Reference Rastorgueva1964: 33), on the other hand, classifies the same dialect as a dialect without /uː/. As for Bukharan Tajik, Kerimova (Reference Kerimova1959: 6) lists twelve Bukharan Tajik words as words in which the vowel length distinction of Early New Persian close vowels is retained. However, only a few of the words in the list, such as /ɕiɕa/ ‘glass’, /suɾat/ ‘appearance’, and /sina/ ‘breast’ are currently in common use among Bukharan Tajik speakers. The vowel length distinction in the close vowels is therefore only marginally, if at all, significant in terms of phonology in the Bukharan Tajik of today. Nevertheless, the vowel length distinction is, albeit only phonetically, still present in the pronunciation of Bukharan Tajik. As can be observed in Table 1, the average vowel durations of the unstressed /i/ and /u/ in /ɕiɕa/ and /suɾat/ are greater than those in /ɕiɕtan/ ‘sit’ and /suɾχak/ ‘reddish’ which do not contain any vowels that originate in Early New Persian long vowels.Footnote 21 (For comparison, the average durations of stressed /i/ and /u/ are also shown in the table, using /ɕiɕ/ ‘six’ and /suɾχ/ ‘red’ as examples.)

Table 1 Average duriation (s) of /i/ and /u/ in different words.

The greater lengths of the unstressed vowels in /ɕiɕa/ and /suɾat/ relative to those in /ɕiɕtan/ and /suɾχak/ cannot be ascribed to the different syllabic contexts (i.e. open and close) in which the vowels occur, because the unstressed /i/ and /u/ in the open syllables in the words /ɕifo/ ‘recovery of health’ and /sukut/ ‘silence’ produced by the female informant are not long.Footnote 22 In fact, in the female informant's pronunciation, the unstressed /i/ and /u/ in /ɕifo/ and /sukut/ are invariably devoiced or elided outright – in contrast, the vowel length distinction of Early New Persian close vowels retained in /ɕiɕa/ and /suɾat/ apparently prevents the unstressed /i/ and /u/ from being reduced in the context in which they are prone to reduction (see the third paragraph of this section).

Intonation

An intonation pattern in Bukharan Tajik that is of particular interest is the one for the polar interrogative. Bukharan Tajik has the sentence-final yes–no question particle /mi/, which it borrowed from Uzbek, but the borrowed particle apparently did not put the rising intonation for the yes–no question into complete disuse.Footnote 23 The particle /mi/ is used frequently in Bukharan Tajik, but the rising intonation for the yes–no question, which is exemplified in Figure 8, is used just as frequently. Note that the pitch contour of the declarative (Figure 7) lacks the pitch rise observable in the pitch contour of the polar interrogative (Figure 8).

Figure 7 /navistet/ ‘You wrote’ produced by the female informant.

Figure 8 /navistet/ ‘Did you write?’ produced by the female informant.

Transcription of recorded passage ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Phonetic transcription

ɕimol taɾafban meomadaɡi ɕamol oftob kati hamdiɡaɾaɕba man kuʨnok ɡufta spoɾ kaɾdaɕtaɡi budan ǁ hamun pajtba ʁavs palto pөɕidaɡi sajohatʨija dida mondan ǀ ki hamin sajohatʨija paltoɕa kaɕonda tonat hamun kuʨnok ɡufta qaɾoɾ qabul kaɾdanba keliɕmiɕ kaɾdan ǁ ɕimol taɾafban meomadaɡi ɕamol budaɡi kuʨaɕ kati ɕamol kunont lekin sajohatʨi dastaɕ kati paltoɕa ziʨ dasɡiɾift ǁ kansakansof ɕimol taɾafban meomadaɡi ɕamol kuʨ saɾf kaɾdanban atkazat kad ǁ badi oftob buɾomadan hamma ʥoj ɡaɾm ɕudanban bad sajohatʨi paltoɕa sɾazu kaɕidanba qaɾoɾ kad ǁ iɕqilib ɕimol taɾafban meomadaɡi ɕamol oftob a χudaɕ dida kuʨnok budaɡeɕban tan ɡitanban iloʥaɕ namond ǁ

Phonetic transcription with interlinear gloss

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (22720162) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan. I gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Adrian P. Simpson and two anonymous reviewers.