Since the late nineteenth century, job seeking has become increasingly linked to organizations and facilities that offer information on vacancies, offer placement services, or undertake recruiting. Labour intermediation became a concern of state policy in Europe and beyond. This was understood, first, as a reaction to social problems – such as poverty, mobility, or unemployment – arising from or exacerbated by industrialization. Second, it was seen as an attempt to organize labour markets, which were perceived as becoming more complex and even chaotic. In that respect, many contemporary experts, politicians, and public servants considered state-run labour intermediation an indispensable tool to match the right person to the right job or position.Footnote 1

Later on, historical research often adopted this view. Yet recent French, British, and US sociological and historical literatureFootnote 2 has pointed out that labour market policy was not a response to pre-existing socio-economic problems but instead contributed to bringing them into existence. It highlights the importance of job placement for the invention of unemployment and the “birth”Footnote 3 of the unemployed. The establishment of labour intermediation therefore has to be discussed as an element of the production of the new regime of work, non-work, employment, unemployment, and unemployability.Footnote 4 Before states began to intervene in labour intermediation, national labour markets did not exist. Rather, there was a variety of different labour markets and labour intermediations, each with its own problems and contestations. Nonetheless, the policies of various European states differed significantly. This becomes most evident if we include the efforts made to survey, compare, organize, and equalize these policies at a national and international level.

The present article focuses on how job placement became an agenda for emerging welfare states and how state-run systems of labour intermediation were established in Europe from the late nineteenth century to World War II.Footnote 5 Recent literature has described the emergence of public labour intermediation primarily as a project of public servants, politicians, and interest groups such as employers’ and workers’ organizations. But that is too narrow an approach given the wide range of practices that shaped the emergence of public labour intermediation, including private and commercial labour exchanges and the job seekers themselves, who have been particularly omitted in research so far. Job placement cannot be restricted to actual public employment exchanges and state policy cannot be understood by looking exclusively at the state. Yet, state policy did play a special role in the making of public labour intermediation by establishing public employment offices that conducted increasingly specialized placement services and by universalizing placement beyond particular occupations and places, thus mediating a variety of interests.

In nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe, a bewildering multiplicity of terms was used to describe organizations and facilities offering placement services. Both national and international statistics, surveys, and research compiled in the first few decades of the twentieth century had great difficulty in determining what services were meant by specific designations – even within the same country. This ambiguity and the confusing terminology are an integral part of the phenomenon in question. For reasons of readability, we will differentiate as follows. The term “job placement” is used to denote all kinds of placement services provided by states, associations, commercial businesses, or other kinds of organizations. Job placement facilities are referred to as “labour” or “employment exchanges”, both terms being used interchangeably. In cases where such a facility was run by a municipality, a province, or a central government, “public” (labour or employment) exchange (or office) is used to distinguish it from private exchanges. The services offered by the public offices varied from country to country and changed over time. Sometimes, such changes were marked by a change in the term used (for example in Germany from Arbeitsnachweis to Arbeitsamt), but more often the names were left unchanged. Finally, the term “public labour intermediation” covers not only public labour exchanges but also the entire repertoire of state policies with respect to job searching as well as the placement and recruitment of workers.

This article has greatly benefited from some early twentieth-century comparative surveys on labour intermediation across Europe and beyond. It also draws on the results of a workshop on the history of job seeking and labour intermediation held in Vienna in 2009.Footnote 6 The authors are currently preparing an edited volume that includes papers from this workshop.Footnote 7

THE EMERGENCE OF AN INTERNATIONAL PROBLEM

In the late nineteenth century, intensive debates emerged in numerous contexts about the existing and future possibilities of job placement as a remedy for social problems (unemployment, vagrancy, begging, for example).Footnote 8 Both within and between states, these debates involved experts, social reformers, scholars, politicians, and public servants,Footnote 9 as well as officials from trade unions, employers’ organizations, and philanthropic associations. Conferences facilitated comparisons between different notions and uses of job placement.Footnote 10 Committees of social reformers, experts, politicians, and public servants organized inquiries and visited labour exchanges in cities at home and abroad. They described their findings in numerous reports, articles, and books, some of which were comparative in character.Footnote 11 Many societies and associations were established at local, national, and international level, ranging from philanthropic associations establishing local employment exchanges to the International Association on Unemployment, which included the question of job placement in its debates and publications.Footnote 12

After World War I, the International Labour Organization (ILO) became an important site for international exchange on the issue of job placement, for instance through worldwide studies of the scope for job placement and related problems.Footnote 13 Apart from assembling and providing information, the ILO developed standards for creating and regulating employment exchanges. States ratifying the 1919 Washington Convention agreed to establish “a system of free public employment agencies under the control of a central authority”.Footnote 14 Moreover, these national systems were aimed at the “total suppression of fee-charging employment agencies”,Footnote 15 because labour “should not be regarded merely as a commodity or article of commerce”.Footnote 16 In this vein, further conventions commonly recommended abolishing or at least regulating commercially run placement agencies.Footnote 17

These international initiatives frequently focused on concrete “solutions” for job placement and job seeking in a few model countries. The British model constituted state-run labour exchanges at a national level, established by the Labour Exchanges Act of 1909. Combined with the national unemployment insurance enacted by law in 1911,Footnote 18 it served as a point of reference for many countries across the world.Footnote 19 However, experts and policymakers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also derived information from elsewhere. Australian social reformers looked not only at the British example but also at early attempts to create public employment exchanges in New Zealand.Footnote 20 In the early twentieth-century Netherlands, the British system was discussed as an option, but the German model of municipal labour exchanges was eventually deemed more appropriate.Footnote 21 Apart from national preferences, specific models evidently attracted certain interest groups. Before World War I, the example of the French bourses du travail – facilities run by trade unions that, inter alia, also offered the placement of jobs – served as an important point of reference for trade unions all over Europe.Footnote 22

The intensity of debates on job placement can best be highlighted by the example of German municipal employment exchanges. Inspired by the example of Swiss cities, which had installed public exchanges in the 1880s,Footnote 23 a network of municipal exchanges was established in the 1890s that would soon cover the entire country. Politicians, scientists, public servants, and social reformers from all over the world travelled to Germany in order to visit municipal labour exchanges there.Footnote 24 Particularly before World War I, the Munich labour exchange (Arbeitsamt) was one of their favourite destinations. In 1908, the facility reported 125 visitors from Germany and abroad, including experts from the US, Belgium, Great Britain, Finland, France, Greece, Japan, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Switzerland.Footnote 25 One year earlier, William BeveridgeFootnote 26 had also studied the placement practices of the Munich exchange, which informed his notion of the potential functions of public labour exchanges.Footnote 27 The annual reports of the Arbeitsamt were regularly sent to labour exchanges not only in Germany but also in Hungary, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Russia.Footnote 28 The functioning of the labour exchange was presented at numerous national exhibitions and conferences, as well as at the International Hygiene Exhibition (Dresden, 1911),Footnote 29 the International Industrial Exhibition (Turin, 1911),Footnote 30 the International Exposition of Social Hygiene (Rome, 1912),Footnote 31 and the International Urban Exhibition (Lyons, 1914).Footnote 32

Yet even though the international dimensions of this exchange are remarkable, particularly before World War I the primary aims of state bureaucracies were to gather information on placement activities and on the supply of and demand for jobs in their own countries.Footnote 33 A major concern was how to count the unemployed. It was a problem that went unsolved, since what being unemployed actually meant was neither clearly defined nor identifiable. In this respect, the development of mathematical statistics proved its practical and administrative value by redefining the problem and developing ways of measuring unemployment as a social fact. It used and combined various materials, such as monthly reports of union-run labour exchanges (in Great Britain, Germany, as well as France), and developed new statistical tools, such as rates and “index numbers”.Footnote 34 Labour offices were maintained especially in state-run systems of labour intermediation, along with the administration of unemployment insurance, thus producing the information that administrative statisticians used to construct their barometers of national labour markets.Footnote 35

OPTIONS FOR JOB SEARCH AND PLACEMENT

The late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European studies revealed multiple ways to earn a living and make use of organizations that offered job placement.Footnote 36 Except for some philanthropic or state-run facilities that provided information on vacancies,Footnote 37 public labour exchanges did not exist before the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

A common practice of job seeking was – and still is – to use social networks provided by family, kin, friends, or colleagues.Footnote 38 This coincided with the recruiting practices of firms that, either directly or through foremen, labour recruiters, or gang leaders, addressed their workers’ personal contacts to fill vacancies.Footnote 39 One of the most important ways to find work was to ask at factory gates, building sites, port entrances, or mines. This practice was known as Umschau (“looking around”) in Germany and Austria, leuren om werk in the Netherlands, and “calling around” in Great Britain.Footnote 40 Guilds, trade unions, relief funds, and associations (such as the Catholic Kolpingverein in central Europe) supported skilled workers who went tramping in search of labour. Servants and agricultural labourers in particular could find a job or position through the “open-air markets” found in some European regions before World War II. Responding to newspapers advertisements became a new way of searching for a job in the nineteenth century, but it never replaced personal ties.

In the final quarter of the nineteenth century, various organizations were established which offered job placement, among other services. At the same time, some existing organizations extended their placement activities. Among the most important organized forms of job placement were commercial placement agencies. According to the available data, in some European countries these agencies were responsible for most of the registered job placements, especially in areas such as domestic service or agricultural work.Footnote 41 There is scant documentation available on these commercially run facilities. The research literature and contemporary surveys suggest that, apart from such commercial offices, placement was often practised on the side by innkeepers, concierges, waiters, warehousemen, travelling salesmen, and peddlers.Footnote 42

Apart from that, philanthropic and confessional associations offered placement and other kinds of support. In some cases they can be regarded as direct forerunners of state-run – particularly municipal – employment exchanges.Footnote 43 Such associations were founded either as general charitable organizations for the poor or to support specific groups such as apprentices, the homeless, prostitutes, or convicts. They created not only offices but also hostels, asylums, wayfarers’ relief stations, and railway missions that offered a variety of services, including job placement.

Trade unions and employers’ organizations likewise founded exchanges as a political tool for industrial action and as an attempt to control the allocation of labour.Footnote 44 But although union-run labour exchanges were important when linked to union-based benefit systems like the Ghent system, their impact – as measured by the number of placements – depended ultimately on the ability to organize workers in a certain branch and/or location. Further job placement activities of lesser significance were reported for schools and political parties.Footnote 45

In the early period, job placement was only one of many services offered. The French bourses du travail might serve as an example: these institutions also offered travel benefits, lodging for wayfarers, and advanced training courses. Furthermore, they served as trade union meeting places, where strike funds and consumer cooperatives were maintained. In addition, they set the unemployable apart from the employable.Footnote 46 Generally speaking, none of these organizations specialized in job placement. At least one of the following services could be found in each of them. Union-run exchanges usually offered services similar to the French bourses. Philanthropic exchanges frequently offered lodging for wayfarers, cheap meals, bathing facilities, and some kinds of migrant benefit. Organizations with confessional backgrounds usually linked job placement to proselytizing. Foremen and labour recruiters not only signed up, but also supervised new workers; they offered credits and helped migrants to integrate socially. Commercial placement agencies allegedly exploited job seekers by combining costly placement activities with lodging and, in the worst cases, ultimately forced young women into prostitution.

Clearly, these organizations and facilities exercised multiple functions and tasks, but what they had in common was that they offered some kind of support to those lacking various – especially social and professional – resources. Examples might include: a young girl from the countryside arriving in the big city to earn a living as a domestic servant; a single casual worker standing alone against an industrial entrepreneur; or a poor household containing more children than could be fed. These unspecialized services made sense in the context of either traditional welfare for the poor or a market for personal services. Anything else – such as the specialized administration of all citizens of a welfare state – was clearly neither necessary nor imaginable.

Most of these organizations were established in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and successfully extended their activities. Thus, it would be wrong to reconstruct the history of job seeking and placement only from the perspective of a nascent system of public labour intermediation. It was partly in response to the exploitative practices associated with commercial employment agencies and partly to fight unorganized forms of job seeking that public employment exchanges were founded. Public labour intermediation was thus developed both alongside and in opposition to other possibilities for job placement. Furthermore, it did not necessarily eliminate these alternatives. Even in countries where legislation granted a monopoly to public labour market administration (such as Germany in 1935Footnote 47), informal ways of finding a job remained important. The range of organizations offering job placement nonetheless substantially declined in states where systems of public labour intermediation were launched, though they did not disappear completely.

PLACEMENT AS A REMEDY: THE EXAMPLE OF MOBILITY

The assumption that job placement entailed important benefits developed in many different contexts. Job placement was seen as a remedy for a variety of social problems. It evolved, for instance, within the most common forms of job searching, such as calling around or tramping without funds, both of which seemed to be unmonitored and (in many respects) risky. Neither mobility nor poverty started with industrialization. Over time, however, increasing numbers of people became predominantly dependent on wages – a condition that became permanent throughout their lives. As a result, they were increasingly exposed to economic slumps. Since there was a high labour turnover in this period of industrialization, employment often being casual,Footnote 48 seasonal, and/or temporary,Footnote 49 most workers constantly had to find and secure work.Footnote 50 It was common practice to look for work in more than one community, which proponents of job placement criticized as ineffective, humiliating, demoralizing, and sometimes even endangering the genuine work seeker.Footnote 51 It could, after all, easily slide into begging, vagrancy, or prostitution. As some critics of the absence of job placement argued, it would become a mere cover for avoiding decent work in the first place.

Up until the twentieth century, the main assumption behind state efforts to police the indigent had been that a distinction could be made between the deserving and the undeserving poor. Drawing this distinction had been the major concern. At the end of the nineteenth century, however, contemporary social reformers and officials began to perceive not only an increase but also a transformation in mobility and poverty. New distinctions and new practical categories emerged. Historians have shown that social reform at the end of the nineteenth century invented rather than discovered the involuntary unemployed and the unemployable.Footnote 52 The problem of a clear distinction necessary for any kind of policing remained, but the particular solutions had changed. The selection of unemployed, unemployable, and workshy turned out to be more a question of collective and rational treatment than of moral, individual diagnosis.Footnote 53

As a concomitant to debates on job placement, comparative studies and reports now dealt with the question of how to distinguish systematically able-bodied genuine work seekers from those vagabonds avoiding work.Footnote 54 Legal repression, punishment, and “re-education” through hard labour remained options for dealing with beggars and vagabonds. Correspondingly though, job placement and support of wayfarers willing to work were regarded as appropriate assistance to the involuntarily unemployed. As a result, wayfarer relief was established in parts of Germany, in the CisleithanianFootnote 55 part of the Habsburg monarchy, and in Switzerland.Footnote 56 These Naturalverpflegsstationen or Herbergen could be initiated and run by charitable religious organizations (as in German provinces) or local communities (as in Cisleithania). While Naturalverpflegsstationen in Cisleithania were regulated and supervised by provincial governments, some German provincial and Swiss governments preferred to intervene by subsidizing wayfarers’ aid. These facilities provided shelter and provision and were supposed to indicate vacancies for (mostly male) visitors.

Nonetheless, these measures normalized the search for work instead of actually mediating labour. Public labour exchanges either built on available facilities for wayfarer relief or integrated them into their own range of activities. In Bohemia, for instance, the 1903 law on labour intermediation turned Naturalverpflegsstationen into labour exchanges, additionally regulating placement procedures and setting up public exchanges where Naturalverpflegsstationen did not exist.Footnote 57 In Germany as well, the connection between Herbergen and public labour exchanges was a constant source of disquiet.Footnote 58 In 1927 the German Unemployment Insurance Act regulated support for wayfarers. For workers in certain trades, building up occupational experience by working in different locations was seen as a possible and desirable option.Footnote 59 Labour exchanges in various countries facilitated labour mobility as part of national policies not to suppress mobility, but to prohibit vagrancy. Apart from being facilitated by public and charitable organizations, mobility was supported by unions or occupational associations.

Besides protecting work seekers from physical and moral dangers, states were also concerned about where they were heading. Moving, for example, from the countryside to the cities – leading to what was apprehensively observed as baleful “rural depopulation”: Landflucht – was a prominent issue, particularly in Germany.Footnote 60 High figures for return migration were commonly ignored, even by later researchers.Footnote 61 Beyond internal mobility, transnational and transcontinental migration also became a topic of regulation, at least after the end of the nineteenth centuryFootnote 62 and particularly after World War I. International placement – especially for women and juveniles – was a matter of concern and regulation.

In the interwar period, many countries largely restricted the employment of foreigners. Bilateral agreements regulated not only seasonal labour in agricultureFootnote 63 but also in industrial work.Footnote 64 In reaction to the demands of organized labourers who feared competition from European immigrants, the US government passed the Alien Contract Labor (or Foran) Law in 1885, which forbade migrants to conclude a contract with a US employer prior to their arrival.Footnote 65 Consequently, migration policy was seen as an important tool for regulating movement, protecting national labour markets,Footnote 66 and prohibiting the exploitation of migrants, while also preventing epidemics, including cholera. Public job placement was regarded as a crucial remedy in such circumstances.Footnote 67

RESTRICTING COMMERCIAL PLACEMENT AGENCIES

In contemporary public debates on labour mediation, however, the critique of commercial employment agencies appears as the main starting point for public measures in most European countries.Footnote 68 The numbers of placements available indicate that commercially run agencies played a major role in finding employment, work, or posts.Footnote 69 They obviously met the needs, for example, of servants who, as a rule, were not organized in unions or associations and who found it hard to call around for posts. Yet this kind of placement service was expensive for the job seeker, and the information provided on vacancies was often false.

When commercial placement was combined with lodging, the businessman had no interest in placing job seekers quickly. Accordingly, commercial placement allegedly induced workshyness, lured women into prostitution, and drove men to drink. Hence commercial agencies were seen as keen to defraud or exploit the jobless, and – since they also encouraged changing positions – to undermine stable labour relations.Footnote 70 Owing both to their significance and their suspected malpractice, commercial agencies were the main targets of criticism by governments, unions, and charitable organizations as well as (partially) by employers. Contemporary critics thus argued that the economic interest of commercial agencies caused harm both to job seekers and the entire economy.Footnote 71 As a result, in most European countries legal regulation and restrictions on commercial placement agencies were the state's first steps towards intervention in job placement.Footnote 72 France passed such a decree in 1852; Austria in 1863. In 1875 Switzerland agreed to the international placement of young persons and adopted further measures in 1892. Regulations were approved in 1883 in Germany; in 1884 in Hungary and Sweden; in 1891 in Denmark; and in 1896 in Norway. New Zealand, Western Australia, and the US state of Iowa also passed regulations at that time.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, such decrees were often replaced by laws. This happened in France (where a 1904 edict was codified in 1910), in Austria (1907), in England and Wales (1907), and in Germany (1910) – to give just a few examples.Footnote 73 Numerous options had to be regulated, and requiring licences was a feature common to most of the laws.Footnote 74 Often criteria were issued concerning eligibility for such a licenceFootnote 75 – not to speak of their location, the requirements for charging fees, their extent, and so on.Footnote 76 A combination with other trades such as inns, restaurants, and boarding houses, or itinerant trades was forbidden, for example in Germany.Footnote 77 Granting licences could be made conditional on local or regional demand for job placement facilities, acknowledged by the respective authorities. Business practices were monitored, and reports to the authorities were made obligatory.Footnote 78 Special emphasis was often placed on protecting young people, on questions of morality, or on the regulation of international placements, including the trafficking of women.Footnote 79 In addition, commercial placement agencies were not supposed to encourage workers to change jobs or breach their contract. Particularly before World War I, the strictness of this policy varied from state to state. In France it was even possible to forbid or abolish agencies, in exchange for compensation.Footnote 80

Outside Europe, where World War I more or less halted this process, such regulations rapidly extended between 1910 and 1920.Footnote 81 As mentioned earlier, in 1919 the ILO recommended taking measures to prohibit the establishment of employment agencies that charged fees or carried on their business for profit. In the years to follow, this aim came to be shared by many countries.Footnote 82 Together with the establishment of public exchanges, it was regarded as necessary in order to prohibit abuses and to organize national labour markets.

Still, the scope of the enacted regulations varied considerably across Europe. Some countries regulated fee-charging placement only with respect to certain occupations, certain types of employment, or on a gender basis. Others legally abolished commercial placement, yet exceptions were possible. In almost every country, the fees for placement were also subject to legal regulations.Footnote 83 In some cases they were fixed, in others it was merely stipulated which party had to pay the fee and under what circumstances. In France, for instance, the fee could be charged only to employers.Footnote 84 In other countries – such as Danzig, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, the USSR, and Yugoslavia – legal provisions required the total or partial abolition of fee-charging placement agencies, either gradually or immediately. In France, local authorities had the power to shut down commercial agencies.Footnote 85

REGULATING AND INTEGRATING: FREE PRIVATE PLACEMENT

Other placement services, defined by the ILO as “private”,Footnote 86 but free of charge, did not seem to be as problematic. Placement services run by benevolent philanthropic associations in Germany (and to a lesser extent in Austria, the Netherlands, and Belgium) can even be regarded as the precursors of public employment exchanges. Typically, these were increasingly subsidized by the municipalities. And they were integrated step by step into communal administrations until, finally, they were run by those municipalities. At the same time, they turned from being associations for fighting poverty to labour exchanges for combating unemployment and organizing the local labour market.

The importance of union-run labour exchanges varied from country to country. They were particularly significant in Great Britain, where unions had long been established and accepted. In France, unions had been allowed to have their own labour exchanges since 1884. In countries such as Germany, Austria, Romania, and Sweden, craft cooperatives ran (or were obliged to run) their own job placement services, albeit with varying efficiency, prior to World War I.Footnote 87 Once public employment exchanges were able to integrate union- or craft-run exchanges, they became more essential in attracting qualified workers.

Similarly, other organizations could be authorized or ordered to conduct placement services. In some countries, such free (non-commercial) labour exchanges were subsidized if they fulfilled certain requirements.Footnote 88 That way, the state could influence policy or implement certain rules.

ESTABLISHING PUBLIC LABOUR INTERMEDIATION

As mentioned before, some effort to establish public facilities that provided information on vacancies can be observed as early as the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Yet these attempts were isolated. In the late nineteenth century, placement services were instituted more broadly, becoming more in the way of modern public employment exchanges. In at least one respect, they were (at least) supposed to contribute to organizing labour markets instead of just offering assorted help to those in need of it.

The comparative surveys carried out in the early twentieth century reveal an impressive variety of options for seeking jobs or placing people, as well as remarkable differences in the practices of public job placement per country. The terms used to describe these exchanges already suggest that: “employment exchange”, “labour bureau”, “labour bourse”, “arbeidsbeurs”, “bureau de placement”, “Arbeitsamt”, “Arbeitsbörse”, and “Arbeitsnachweis”. Some of these facilities merely provided information on vacancies, while others were more actively engaged in the process of matching men and women to jobs. Even if the same terms were used to describe organizations, practices within a given country were not necessarily similar. To some extent, like other possibilities for job placement, early public employment exchanges were not specialized organizations, for they also provided bathing facilities, lodging for wayfarers, cheap meals, and legal advice. Furthermore, some countries had transferred the task of public job placement to the railways,Footnote 89 the police,Footnote 90 the courts, or post offices,Footnote 91 since these facilities were already present across the country and could provide modern means of communication, such as the telephone.

The multiple ways of practising public job placement are indicated equally in the broadly formulated justifications for making this problem a state responsibility. Public employment exchanges were expected to organize the labour market(s)Footnote 92 by reducing casual labour,Footnote 93 and identifying the real unemployed so as to separate them from the unemployableFootnote 94 or workshy.Footnote 95 They were intended as instruments to enhance national competitiveness by enabling a more efficient use of human resources.Footnote 96 Furthermore, they were supposed to fight poverty and thereby relieve the cities of the burden of supporting the poor.Footnote 97 Other tasks assigned to these public agencies were to control migration, combat vagrancy, and stabilize employment relations. Public employment exchanges promised to help control labour mobility and help employers deal with labour shortages. Moreover, they were expected to assist in integrating former convicts and reservists as well as in reducing the “malpractices” of which other placement services were accused. In the context of World War I, public employment offices were meant to monitor the labour force, reintegrate war invalids and returnees, and by doing so diminish social unrest.

Although labour intermediation was chiefly a concern of larger cities, some state policies reached out beyond urban economies. Whereas in Great Britain public labour exchanges were designed to cope with predominantly urban problems,Footnote 98 their prime function in Italy was to locate work for agricultural labourers.Footnote 99 These examples indicate that it would be misleading to describe these facilities as simple national variants of a general system of public labour intermediation. Their objectives and scope could be fundamentally different.Footnote 100

The practical organization of labour intermediation by European states thus differed in two respects at least, namely with regard to the actual involvement of different state levels and with regard to how states organized labour intermediation. No clear and unanimous distinction could be made between state-run and other placement activities. Public labour placement could be initiated, established, or run either by municipalities (in Switzerland,Footnote 101 the Netherlands,Footnote 102 Belgium,Footnote 103 in Germany until 1927, and in some cities of Austria-HungaryFootnote 104), by provincial authorities and/or districts (in Bohemia,Footnote 105 and GaliciaFootnote 106), or by national authorities (in Great Britain since 1909Footnote 107). In many cases, this implied that the central state would be involved only marginally or hesitantly. In a number of countries, however, the laws stipulated that municipalities of a certain size had to set up labour exchanges. This already happened before World War I in Bohemia.Footnote 108 In France, pursuant to a 1910 decree, every city with more than 10,000 inhabitants was supposed to have a public labour exchange.Footnote 109 Finland had a similar regulation from 1930 on; Bulgaria from 1925 on; and Denmark from 1927 on.Footnote 110 In Germany, under the 1927 German Unemployment Insurance Act every municipality had to be covered by a public labour exchange.Footnote 111

However, a combination of various forms of exchange, funding, and regulation could often be observed. In pre-World-War-I France, for instance, labour exchanges were primarily financed by municipalities, although the state had started to provide some limited funding in 1911. During the war, nonetheless, every town or city was obliged to set up labour exchanges administered by joint committees. Additionally, offices régionaux de placement (regional labour exchanges), offices départementaux de placement (district employment exchanges), and a central office in the Ministry of Labour were established.Footnote 112 In Italy, commercial job placement was outlawed in 1928–1929.Footnote 113 State-run labour exchanges were permitted, as were “acknowledged labour exchanges” – communal labour exchanges, employer/union labour exchanges (either jointly run or run by one if acknowledged by the counterpart), and charitable placement. And there were also joint labour offices in regions without public employment exchanges. Most such placement services were supervised by provincial offices and a central employment office. Districts could be merged so as to combine employment services for certain occupations.Footnote 114

Furthermore, in many European countries trade unions and employer organizations were involved in administering public employment exchanges. In several countries, even private job placements were conceived more as complements to public employment exchanges than as adversaries. According to the 1934 ILO survey, most countries had taken one of the following measures.Footnote 115 First, private placement services could be allowed to supplement public placement for certain occupations in certain places (as in Finland, Italy, and Poland). Second, private placement services might be supervised and regulated (as in France, Finland, Germany, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Spain). Third, private and public employment exchanges could cooperate by exchanging information, especially about vacancies that one or the other was not able to fill (as in Denmark, Switzerland, and in Hungary). Fourth, private exchanges might be fully integrated and absorbed by public systems (as in Belgium and Bulgaria). In the Netherlands, labour exchanges could apply for public recognition. In Great Britain, unions were able to negotiate a contract with public offices in order to administer employment benefits.

Within a national system of placement organizations and facilities, a variety of measures could secure an extensive clientele and supply a preferential position to public employment exchanges.Footnote 116 Yet compulsory usage both for employers and employees, as was the case in Italy,Footnote 117 was not common. In Germany, a de facto public monopoly for part of the labour market existed even before a monopoly was legally enacted in 1935, inasmuch as public enterprises had to recruit through public employment offices.Footnote 118 Private enterprises were not required to use them, but collective agreements might include obligatory clauses (in 1925, this applied to 44 per cent of all such agreements).Footnote 119 In Germany, it was also formally possible to impose obligatory reporting of vacancies by employers, but this was not put into practice. In Poland, all enterprises covered by unemployment insurance – with the exception of state-run or municipal enterprises – had to report vacancies.Footnote 120 This possibility was at least discussed in other countries as well. In addition, public labour exchanges could openly advertise their services in order to gain the trust of employers and employees.Footnote 121 Probably the most important measure for establishing and securing a preferential position for public employment exchanges was to require people to register at a public employment exchange in order to be eligible for unemployment benefits.

On the one hand, authorities acted by regulating, restricting, and funding on the basis of certain principles, especially those of free placement and joint committees. They authorized or delegated intermediation to organizations or municipalities, or they integrated various forms of placement by setting up community or state-based placement. From country to country, public and private placement services were distinguished in different ways.Footnote 122

On the other hand, however, public placement did not simply impose its own rules. It also adopted – and adapted – principles of private placement services: German and Austrian public labour placements attempted to implement “individualized” placement practices for domestic servants that seemed to be founded on the attractiveness of commercial employment agencies. This adaptation of principles of alternative placement services also became evident when public employment exchanges were linked with the administration of unemployment benefits. As a result, the willingness to work as a criterion for support was not an invention of state unemployment insurance.Footnote 123

Even before state benefits were introduced, the statutes of occupational associations and union relief funds defined their respective requirements for support. For example, circumstances deemed legitimate included losing or giving up employment, taking on employment, or being obliged to relocate. Moreover, a legal distinction was drawn between people “out of work” and those who were “unemployed”. Yet placement and benefits were supposed to enable people to stay within their own profession (at least for a certain period of time) and not to have to accept just any wage or any labour condition. Support was also intended to strengthen union impact in industrial action; hence union members were expected to fit in politically.

Clearly, the state adopted and adapted principles selectively, while sometimes altering them. What is more, national measures and services were not always welcomed or accepted. Unions and labour movements at times mistrusted the stateFootnote 124 when it attempted to organize labour intermediation, inasmuch as job placement and benefits were crucial when there were strikes. Furthermore, there was widespread concern that state intervention might lead to bureaucratization or to standardized placement without concern for an individual's trade.Footnote 125

Public labour exchanges gained considerable significance in the first few decades of the twentieth century, particularly because they could be used to serve different interests. State-run enterprises, for instance, became key factors in the economies of the emerging welfare states. The modern governmental agencies also established rational recruiting, thereby adopting a principle of regularity crucial for the new employment regime.Footnote 126 In the course of World War I, public placement measures were taken up in many countries. Controlling the economy on a nationwide level became indispensable, and joblessness was the problem to be solved. War invalids and former soldiers needed to be economically integrated.Footnote 127 Such developments were not always sustained though. In the US, state-run employment exchanges were scaled down considerably after demobilization, and Great Britain and Canada both considered the same option.Footnote 128 By contrast, a comparatively smooth expansion of public employment exchanges took place in Germany and Austria.

In the course of time, the considerable variety in public job placements in a number of countries began to decline, albeit quite slowly. Comparisons became easier after the 1913 survey by Becker and Bernhard and later ILO surveys. Relevant ILO recommendations, however, were not always put into practice.Footnote 129 Yet according to an ILO survey of 1934, most countries either had laws concerning labour exchanges, or they regulated placement laws and decrees pertaining to unemployment insurance (Austria and Germany being two examples). The principles of free placement and joint committees of representatives of employers and employees seemed to have been broadly accepted even if they were realized in different ways and to various extents.Footnote 130 Most countries additionally had central labour exchanges for supervising and coordinating local and provincial offices and for exchanging information between various exchanges.

PUBLIC JOB PLACEMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

The crucial step in establishing the predominance of state employment exchanges in the process of organizing national labour markets, both in Europe and the United States, was to connect them to unemployment insurance. In a 1936 survey on recent publications, Harry D. Wolf emphasized:

In the administration of unemployment insurance, a system of employment offices is necessary to receive claims of applicants and to investigate their validity, to apply the work test and to disburse benefits. On the other hand, experience here and abroad indicates that in the absence of unemployment insurance there is a tendency on part of both employers and employees to ignore the services of the employment offices and thus to defeat their primary purpose, namely, a systematic organization of the labor market, and a more effective use of our resources, human and otherwise.Footnote 131

As a result, one ought to distinguish between various forms of unemployment relief. First, some countries established nationwide unemployment relief whereas others subsidized unemployment funds of associations, trade unions, or municipalities.Footnote 132 Second, compulsory insurance should be distinguished from voluntary insurance. Up to 1933 compulsory unemployment insurance had been established in Germany, in Queensland (Australia), Austria, Bulgaria, Great Britain and Northern Ireland, in Italy, Poland, and in twelve Swiss cantons. Voluntary insurance had been established in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway, the Netherlands, eleven cantons of Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, and in Spain.Footnote 133 Apart from that, almost every European country had made provisions for unemployed workers in one form or another. Public employment exchanges varied with the actual form of provision. And by administering unemployment insurance, public placement gained a hitherto unmatched effectiveness in defining unemployment, thus identifying and dealing with those who were involuntarily unemployed.

In fact, choosing the unemployed by administering them collectively and bureaucratically was the only possible solution to the old problem of counting the “real” unemployed – something which had haunted debates on unemployment from the beginning.Footnote 134 Unemployment insurance could practically select the employable from among the unemployable, the latter of whom could then be turned over to other institutions of the “welfare state”, such as public welfare, old age or disability pension providers, the penal system, and psychiatric institutions. Evidently, these categories remained ambiguous and disputed, as in the case of those elderly unemployed assigned to early retirement. Insurance was effectively dividing the old category of the poor into stratifiable and stratified individuals who continued to be regarded as part of the national economy, and all others.Footnote 135 Unemployment insurance and benefits formally defined a status, permitting individuals to understand their situation as unemployment, even if they were casually employed.Footnote 136 This resulted in the emergence of the unemployed as a phenomenon of the modern economic system and its cycles, thereby personifying a status beyond both a person's responsibility and reach.Footnote 137

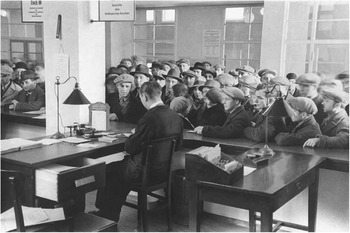

Figure 1 “Arbeitslosenunterstützungsstelle in Steyr” – office administrating unemployment benefits in Steyr (Upper Austria), 1932.

Photograph: Lothar Rübelt; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien. Used with permission.

In this manner, public employment exchanges became increasingly specialized. Other tasks they had fulfilled at first (like other organizations operating as placement services) were now relinquished. Unskilled workers too were overrepresented among those who used public placement.Footnote 138 Still, there could be divisions specialized in certain occupations, such as assisting those who were (or were supposed to be) most in need of regular employment. Yet in the course of time, enlarging the clientele was actively promoted. Once it was seen as an urgent problem, more and more kinds of wage earner were addressed. Consequently, public labour exchanges became increasingly generalized. In addition, they developed and formalized methods of placement, such as psychological tests for determining a client's affinity or aptitude for particular occupations (or vocations).

This process of specialization and universalization demonstrates that the old regime of policing “the poor” – a distinct class, almost a world of its own – had lost significance. Instead, a bureaucratic administration of increasingly unified national labour markets was favoured, which might encompass all employable citizens. In combination with state unemployment benefits, public labour intermediation – like other institutions of the emerging welfare states – could be experienced pragmatically as the relationship between citizens and the state. Accordingly, even more people without work considered their situation as unemployment.Footnote 139

NORMALIZING LABOUR MARKETS

The predominance of labour intermediation by facilities and organizations in general in the modern labour market and the supremacy of public labour placement in particular (as claimed by many European states in the interwar period) appear to be primarily an effect of the emerging bureaucratic mode of labour market organization. The invention, definition, and administration of labour by institutions of the new welfare states was a consequence of greater (quantitative) importance than might be suggested by contemporary – i.e. state-run – data derived from public labour market policy. Research has often reproduced this official perspective by focusing on those facilities operating as placement services as well as on public labour statistics. Thus, it was assumed that the official perspective amounted to an exhaustive description of the entire phenomenon of labour intermediation. Yet this picture must be expanded to include the entire range of documented and undocumented ways of finding work.

Licht points out that according to a 1936 survey only 10 per cent of respondents in a sample of 2,500 Philadelphia workers of all age groups took advantage of diverse institutional offers, i.e. newspaper and radio advertisements, placement agencies, and school referral services;Footnote 140 90 per cent found work with the help of family intervention, personal initiative, or contacts. According to Licht, the practical importance of “formal agencies and institutions” also varied highly throughout the life course and according to a person's gender and type of occupational training. Although Licht's results are based upon unique sources, his observations on Philadelphia can be complemented by further studies.

In a recent contribution, Woong Lee argues that public labour exchanges in the US were used by 2 million job seekers annually (c.5 per cent of the total labour force) in the 1920s. Yet in the 1930s, due to the 1933 Wagner-Peyser Act and the 1935 Social Security Act, this figure rose to nearly 12 million job seekers per annum.Footnote 141 In Great Britain prior to 1914 less than one-third of all placements in insured trades were made by the recently established public labour exchanges.Footnote 142 The Ministry of Labour estimated that in the 1920s and 1930s less than one-third of the total labour turnover was organized by public labour exchanges – a share that David Price believes is still too optimistic.Footnote 143 For Germany, Anselm Faust estimates that both public and private non-fee charging labour exchanges were responsible for perhaps 30 per cent of the total labour turnover in 1912.Footnote 144 By and large, then, people made selective use of public placement.

Unemployment benefits nonetheless treated people selectively, sometimes excluding agricultural labourers, domestic servants, the young and/or elderly, as well as others. In the interwar period, many people were still not insured. Not all kinds of work were equally considered part of the labour market, and not all people without employment understood themselves to be unemployed. Many ways of earning a living did not fit neatly into the idea of gainful employment. Jessica Richter's work on women working in service in interwar Austria, for example, confirms that they frequently changed posts – even alternating with helping out in one's family – which usually meant losing their accommodation as well.Footnote 145 Her work and Irina Vana's systematic comparison of autobiographical accountsFootnote 146 highlight something similar: the way being out of work was handled and understood depended greatly on how a person made a living – not to speak of their occupational training, the kinds of employment sought, integration in a household, and especially entitlement to unemployment benefits. Yet the emerging official categories of “decent” employment or unemployment became an unavoidable reference. Even those who tried to avoid it had to reckon with it.

To a great extent, employers shaped public employment exchanges. Consistent with Licht's study, enterprises preferred using existing informal contacts and networks.Footnote 147 Similar observations can be made for other historical milieus in Europe.Footnote 148 Public employment services, as argued above, often organized help for the supposedly needy along old philanthropic lines. These either operated in niches where informal exchanges of information did not work,Footnote 149 or they addressed persons who had lost touch with such networks. Specialized job placement emerged only after state-run job placement had become established. Efforts made to decasualize the English labour market (Beveridge's central desideratum) were unsuccessful;Footnote 150 if anything, entrepreneurs in the relevant trades (shipbuilding for example) scarcely used public employment offices. Similarly, Malcolm Mansfield points to the 1920 Report of the Barnes Committee, which was charged with evaluating the employment offices. That report noted that public employment offices were used by 141 shipbuilding companies to recruit 2,500 workers, whereas 21,000 posts were assigned by “direct contacts”.Footnote 151

Hence, even after the formal authority of public placement services had been established and nationwide labour markets organized (i.e. invented and defined), state-run job placement remained only one of several possibilities for finding work or recruiting workers. Even in countries such as Italy or Greece, where a monopoly of public labour exchanges took hold in the course of the twentieth century, the share of placements made centrally did not exceed those in countries without a state monopoly.Footnote 152 People in search of employment and those seeking employees not only utilized institutions for different purposes. They also combined different methods to achieve these goals. It is difficult to clearly distinguish the array of practices or relate them to a singular institution, as suggested in official reports and insinuated by the statistics collected by the welfare states. Therefore, to include the range of different ways in which labour exchanges were used or how a person's search for work was perceived in the historical description of public job placement is neither merely illustrative nor morally obligatory. It is crucial for comprehending the social effects of state administrations.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has highlighted the ways in which labour intermediation became a concern of the state and how state-run systems of labour intermediation were established and operated from the late nineteenth century to World War II. Although public labour exchanges were important tools for instituting public labour intermediation, state policies of job placement cannot be reduced to the activities of these facilities. Rather, the state adopted job placement as an agenda by regulating, constraining, prohibiting, or simply influencing the possibilities for job placement. It subsumed and altered the existing options and initiated a slow process of specialization, universalization, codification, and homogenization at national levels.

Amid the appearance of normalized national (and international) labour markets, state labour exchanges became the dominant reference point for all activities – even to those who were excluded from or opposed to them. Fewer and fewer people could avoid dealing with these institutions in one way or another. Accordingly, job placement should be examined as a field of relations between state policies (enacted by local, provincial, and federal levels of state authority), trade unions, employers, philanthropists, scholars, commercially run agencies, and – if nothing else – job seekers. The making of public labour intermediation, a new and crucial type of labour market policy, was a collective process involving activities that were all in one consensual as well as antagonistic. It cannot be reduced to a mere effect of the state changing its mode of governance. The problem of organizing the labour market and the solutions to this problem were produced alongside each other by the same activities.

The establishment of public labour intermediation differed from country to country. This article has attempted to demonstrate this variety by highlighting examples from all over Europe. However, the fact that they emerged concurrently across nations was not their least significant similarity. It is, in fact, a remarkable phenomenon, inasmuch as the problems that systems of public labour intermediation were intended to address were not the same throughout Europe. Moreover, they were addressed in different social-scientific and political contexts, allowing us to conclude that the policies leading to the establishment of public labour intermediation demonstrate also an intrinsic logic (administrative, political, social scientific, for instance) that has to be taken into account.