Introduction

At some time after 1644, the celebrated literatus Zhang Dai (1597–1689) recorded in his diary Taoan mengyi [The Dream Collection of Taoan] the conditions under which both prostitutes and courtesans flourished during the last decades of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In a short essay entitled “Yangzhou shouma” [“The ‘Lean Horses’ of Yangzhou”], he wrote:

In the house of “thin horses” customers were treated to tea and seated to wait for the women. A matchmaker led out all the women, one by one, and gave them instructions; each woman then performed a series of movements for the customer, first bowing, then walking several steps, turning to face toward the light, drawing back her sleeves to show her hands, glancing shyly at the customer to show her eyes, reporting her age, and finally revealing her bound feet. An experienced customer could determine the size of the feet by listening to the noise she made when she walked around; the louder the noise from her skirt, the bigger her feet because, if she lifted her skirt to walk around without rustling the fabric, her feet would be revealed. The customer, if not satisfied with any woman, was expected to reward the matchmaker and each servant several wen before he left. If he decided to select one of the women, he would put a golden hairpin in her hair near the temple […].Footnote 1

And so it might go on, day after day, inspecting woman after woman, tipping matchmaker after matchmaker, until the girls with their powdered faces and their red dresses faded into an indistinguishable blur in which discrimination became impossible.Footnote 2

Yangzhou was not the only location in late Ming China where prostitution and the female entertainment industry thrived – in municipalities all along China's littoral, from Guangzhou to the magnificent cities of the “Lower Yangzi region” (which include Suzhou, Hangzhou, and nearby Nanjing) to the capital Beijing, as well as in inland towns and commercial trading posts, there was a vibrant and highly profitable trade in human beings. As Xie Zhaozhe (1567–1624), a well-known observer of Ming life, wrote about the ubiquity of prostitutes: “In the big cities they run to the tens of thousands, but they can be found in every poor district and remote place as well, leaning by doorways all day long, bestowing their smiles, selling sex for a living.”Footnote 3

Given the ambiguity of Ming population figures, it is extremely difficult even to approximate how many persons were involved one way or another in prostitution and the entertainment industry during the Ming dynasty. With a general population figure by the early seventeenth century of c.175 million, as estimated by Timothy Brook,Footnote 4 we may assume, using Xie Zhaozhe's quotation, that some 1–1.5 million persons would have laboured in this sector. According to the taxonomy of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, this figure includes “labour relation 6” – servants within the household, i.e. those persons who worked within houses of prostitution, as service personnel (cooking, cleaning, fetching, and other domestic tasks) – and “labour relation 14” – wage earners who engaged in sexual relations for a salary. But within this latter category there is a tremendous variation with regard to status and income, from lowly street walkers to “high-class” courtesans, who could be extremely wealthy, living off their patrons as well as off the rent from the properties they owned.

Yangzhou, of all places, seemed to exemplify all that was reprehensible about commercial sex – by the second half of the Ming era Yangzhou had become the “national centre for the procurement of beautiful girls”.Footnote 5 The phrase “lean horses” originated in a poem by the Tang dynasty poet Bo Juyi (772–846) in which he lamented the speed at which the ownership of Yangzhou young prostitutes changed hands, and by the Ming era the expression had become a term reserved for girls sold on the Yangzhou market. Among Ming contemporaries, Yangzhou was known for its “production of women” (in the sense of producing apples or other commodities) – literally, yang shouma [raising young girls for sale into concubinage or prostitution] – in contrast to the reputation of other locales, with their “secluded and virtuous wives and daughters”.Footnote 6

Elite women, i.e. the wives and daughters of men who staffed the imperial bureaucracy or served as leaders in local communities, did not show themselves in public, but this does not mean that they were immune to the rapid economic and social changes occurring during the second half of the sixteenth century. This was a time of extensive economic development and intense commercialization, manifested in an increased degree of local and regional agricultural and manufactured product specialization, the expansion of textile and porcelain industries, growing overseas exchange, large inflows of bullion, an improved transport and communications infrastructure, and, not least, a vibrant publishing industry.Footnote 7 Cities flourished as never before: urban prosperity stimulated the promotion of cosmopolitanism, anonymity, and relative freedom in the attendant pleasure districts, which attracted a wide range of clientele, from literati and students seeking relief from the pressures of studying for (and failing) the civil service examinations, to sojourning merchants requiring lavish, conspicuous entertainment for doing business and for their own gratification.Footnote 8

The burgeoning economy also spurred a printing boom which produced a wealth of new reading materials, from fiction and drama to handy “daily” encyclopedias that reached a wide reading public, including women. Courtesans who were schooled from a young age in reading and writing poetry, as well as in singing and dancing, assimilated this growing appreciation of print culture into their work. Also, in upper-class circles, it was now not uncommon for families to provide female kin with the opportunity to acquire literacy and to allow them to engage in literary activities.Footnote 9 Thus, by 1600 women from privileged backgrounds as well as courtesans formed part of a new reading public, “took up the red brush”, and demonstrated their literary acumen and artistic skills.

While upper-class female writers confined themselves to family, and local networks of other women in private quarters, courtesans showed themselves in the public domain, which meant, in the long run, that their lives and their status in society took on an entirely different hue – one that would criss-cross the values and norms of numbers of male writers and officials, and eventually their wives and daughters.Footnote 10 The late Ming witnessed widespread anxiety about how the tremendous material growth and monetization of the economy were damaging the moral fabric of society, a situation which led some Confucian scholars to seek ways and means to correct and improve the ethos of the social order. Within this concerned elite were those who came to link contemporary political and intellectual controversies and themes with the marginal status of courtesans: ultimately, they steered these women into the Confucian moral universe, a phenomenon unprecedented in Chinese history. Prostitutes, on the other hand, unless they were lucky enough to gain literacy via their “foster homes”, would remain outside this intersection of ethics and changing values among the elite literati.

It is against such a background that we consider prostitutes and courtesans in late Ming society – their legal and societal position, their shifting roles vis-à-vis the male scholar-elite and female upper-class writers, and what changes occurred at the end of the Ming that affected their status.

Definitions, institutions, and legal norms

According to contemporary Chinese judicial regulations, both prostitutes and courtesans were classified as “entertainers”, and, therefore, they had the status of jianmin [mean people], which formally made them “outcasts” in Chinese society.Footnote 11 In the Ming era, the law recognized only two kinds of person – “mean”, or commoner (liang), who was considered “good” or “virtuous”. Mean people were outside the four commoner status groups: gentlemen (scholars), farmers, artisans, and merchants. The chief bias against mean people was that the work they performed was humiliating or polluting, or both, or of little or no value to society – such as entertainment.Footnote 12 This meant that not only women working either as performers at the imperial court or on the street as prostitutes but also men who were musicians were not immune from this label.Footnote 13

While the Ming code did not prevent ordinary male commoners from marrying either courtesans or prostitutes, the top group within the four status ranks, i.e. scholar-official, was forbidden from doing so, though this did not stop them from taking attractive women (either courtesans or lowly prostitutes) as concubines to live in their marital homes.Footnote 14 Since the law dictated that a Chinese man could have only one wife, it was not uncommon for rich men to acquire a series of concubines to mark their status and boost their prestige. A married man who still had no heir at the age of forty was actually encouraged to take a concubine.Footnote 15 Given these conditions, one may conclude that neither prostitutes nor courtesans formed an endogamous group in late Ming society, and they cannot be termed pariahs.

Nevertheless, despite the relatively low formal status that these two types of women shared, there were certain obvious differences between them. The top-class courtesan, known by the expression mingji [famous courtesan], usually had a cultured upbringing to prepare her for serving clients.Footnote 16 Besides her bestowal of sexual favours, she was also expected to indulge with her patrons in the fine arts – playing the zither or chess, or engaging in calligraphy or painting.Footnote 17 While prized for her beauty and sexual charms, the true function of a courtesan (as opposed to a prostitute) was that of a “professional hostess” who was educated and cultivated in skills such as conversation, knowledge of classical literature, recitation of poetry, dancing, and musical performance.Footnote 18

Her ability to write poetry was a key tool in her trade because literary exchanges were fundamental in the communication between her and her clients. The most talented courtesans also functioned as counsellors on matters of refinement, as the “resident experts on the elaborate esoterica of a romanticized affective life”.Footnote 19 They were responsible for creating an aesthetically pleasing atmosphere, whether within a brothel or in private apartments where elite men would hold poetry parties or drinking contests. One of the most important locations where courtesans made their mark as talented and amusing companions was in the setting of gardens; in these beautiful, rustic, and artistic sites people congregated to enjoy leisure pursuits in the open air. Here courtesans met their patrons to enjoy intense cultural exchanges on poetry and singing. In some cases, courtesans actually owned gardens and used them as a form of financial investment.Footnote 20 Thus, one may say the late Ming courtesan enjoyed a certain “fluidity”: she moved between the nether world of the high-class brothel and the exquisite surroundings of scholar gardens.

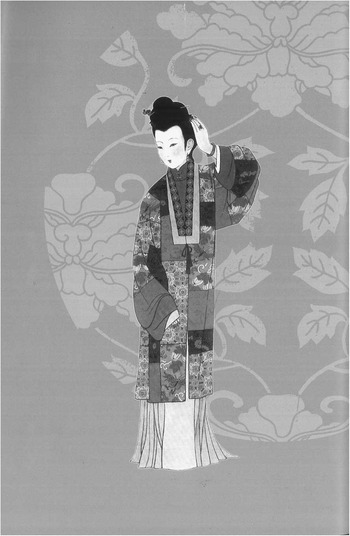

The courtesan's rich-looking appearance also distinguished her from the prostitute. By the late Ming, the once strict dress code forbidding certain forms of dress and adornment to particular status groups of the population was fading, and sartorial regulations were becoming a thing of the past.Footnote 21 Thus, depending on their personal wealth, courtesans were known to display themselves in the most opulent of fabrics and with the grandest accessories, including jewelled headdresses. Silk, a textile traditionally worn only by those of the privileged highest social status, now became integral to the courtesan's wardrobe. The wearing of embroidery, damasks, brocades, and other patterned silks in dark colours such as dark blue, green, and scarlet, once the exclusive right of upper-class women, became negotiable by the second half of the sixteenth century. In illustrated novels, such as Jin Ping Mei [The Plum in the Golden Vase], the female characters who are the wives and concubines of a merchant are attired in clothing and jewellery that was once considered entirely inappropriate to their class.Footnote 22

Figure 1 Courtesan in Ming “patchwork” (shuitian) coat with dress. Source: Hua Mei, Chinese Clothing (Beijing, 2004), p. 56. Used with permission.

While elite courtesans generally confined their public appearances to within the entertainment quarters, prostitutes were truly “women of the street”. As waiji [common whores], they plied their trade openly in the public domain. In the early evening hours, prostitutes emerged from their living quarters and hung around the doorways of tea houses and drinking places in search of business.Footnote 23 In the capital Beijing during the Wanli era (1573–1620), a customer could pay some seven wen to get an hour in bed with a woman who would parade nude before copulation.Footnote 24 There was also a category of “official prostitutes” (guanji), the descendants either of Mongols who had remained in China after the defeat of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, or of condemned Chinese officials.Footnote 25 These women often had the surname Dun or Tuo, indicative of their Mongol heritage. They belonged to the bottom rung of the “mean people”, and had relatively little chance to liberate themselves from their economic bondage and to change their lifestyles.

Notwithstanding these clear differences between prostitutes and courtesans, both groups faced a certain ambiguity about the permanence of their social station. Courtesans could, and did, marry their patrons or clients (even among the upper-class elite, despite the legal interdict) while common prostitutes could be bought as concubines and function in well-to-do households as second wives. Fathers sold daughters, and even husbands sold wives (with the excuse that they had misbehaved).Footnote 26 Such transactions were formalized by a contract, like the one recorded in the 1596 household encyclopedia Wanbao quanshu [Encyclopedia of Myriad Treasures]:

In [name blank] village, I [name blank] had a daughter, [name blank]. When she reached adulthood, I arranged her to be the concubine of [name blank]. The engagement price was received today at the moment when this contract is completed. In the auspicious day and time, she will be sent to her husband's household. With heavenly blessing, she will produce many children. The daughter, as my biological child raised in the family, was never engaged before. There is no cheating in this sale. As soon as she is taken into [name blank's] family, she belongs to [name blank]. In case she runs away, I will chase her and return her to you. We will have no complaint even if she dies. Her death is not the owner's responsibility, but her destiny. This contract is the evidence of marriage.Footnote 27

Given that this encyclopedic source served as a guide to the lower classes anxious to acquire practical information in a rapidly changing commercial world, the publication in it of this contract may be evidence of the need to formalize the trade in human beings at this time, as well as of the increasing frequency of this practice.Footnote 28

In any event, moral confusion permeates this kind of human trafficking: in a society that highly prized the Confucian values of filiality and obeisance, a daughter who was sold to become a maid or prostitute in the entertainment quarters to help her family escape poverty was worthy of praise.Footnote 29 Moreover, she herself might see her new surroundings as an opportunity to improve her own material circumstances in a location where beauty, talent, and accomplishment were valued. On the other hand, the Confucian condemnation of lower-class families for selling their daughters should not distract one from the fact that upper-class families frequently bought such women, as well as concubines and servants. As prices for food and cloth rose during the late Ming, many ordinary families had difficulties meeting their expenses and the sale of a daughter became a solution. Price indicators show that during the Zhengde reign (1506–1521) in Nanjing, for example, an ordinary family of average size (around five people) could have enough meat and vegetables with about 20–30 wen a day (with pork costing around 8 wen per jin).Footnote 30 But around 100 years later, with the costs of food rocketing (pork, for instance, cost 40 wen per jin), people found it increasingly difficult to provide for themselves, and thus the sale of a female relative for 100–200 taels of silver could bring relief to the remaining family members.Footnote 31

Despite its cultural brilliance and economic growth, the late Ming also saw increasingly sharp economic and social differences between rich and poor, merchant and farmer, and official and commoner, which did not go unobserved by scholar-officials and intellectuals. How they dealt with the disparities between these groups varied considerably, however.Footnote 32 A recent study of charity at that time challenges any facile explanation that institutions of benevolence and goodwill, such as soup kitchens and medical dispensaries, were simply a response to poverty and social unrest.Footnote 33 Instead one may look at how the social and economic changes themselves stimulated new ways of thinking about the ethos of Ming society, and the capacity of individuals to approach and absorb Confucian ideals. Literati writings dating from the late Ming exhibit a mixed intellectual agenda, revealing the tensions between these men's academic tenets, moral convictions, and personal feelings. Conventional pity for the oppressed courtesan (or even the condemned prostitute) did exist, but this period also saw the development of another vision of this woman that altered both their status and their place in the Confucian moral universe.

The transformation of the courtesan ideal in late Ming China

Late Ming intellectuals did not consider the plight of courtesans (or prostitutes) as sinful or wicked, but rather as something unfortunate.Footnote 34 That rich and famous courtesans or poor and obscure prostitutes sold their services and their bodies in exchange for money was pitiful, and maybe even fatalistic, but not really a matter for reform. While some men of letters pursued the grandeur et misère of courtesan life as the subject matter for plays and novellas,Footnote 35 few of them “conceived, much less proposed, the abolition of these women's bonds to servitude”.Footnote 36 An air of misfortune was attached even to the stars of the profession.

Such attitudes differed from earlier views of this category of woman some 500 years before when, during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), debates raged among literati and officials about the proper place of courtesans in “polite society”. As Song government reformers tried to revitalize Confucianism, they regarded the courtesan as a troubling and contestable figure who was a threat to the stability of the regime. They believed her very existence was a menace “to the social and moral purity of the upper-class male literatus”.Footnote 37 And as for officials who commingled with her, they were considered “debauched, and emblematic of evil and irresponsibility”.Footnote 38 Such attitudes were derivative of an altering Chinese cultural tradition that emerged at the start of the Song era. As Peter Bol has argued, while Song neo-Confucians shifted the focus of learning away from literary-historical traditions to the cultivation of ethical behaviour, they created a new body of texts, doctrines, and practices that came to define “This [Chinese] Culture”, which lay great emphasis on ethical-philosophical ideas and principles.Footnote 39

Over time, the negative attitude towards courtesans hardened, and both the Yuan (1279–1368) and early Ming regimes tried to discourage their presence in government-sponsored entertainment, such as banquets. The first Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (r.1368–1398), issued a decree threatening severe penalties for officials caught having sexual relations with female entertainers.Footnote 40 But during the course of the Ming era, and especially by the mid-sixteenth century, courtesans were no longer thought about in this way, and towards the end of this period they became “a cultural ideal”.

The story of how these women became powerful symbols of morality and virtue is complex, and compels us to turn once again to intellectual developments during the Southern Song. The Confucian revival of that era was dominated by the ideology of lixue [study of principle], which put great emphasis on the moral perfection of the individual, an ideal that was achievable through the study of a number of prescribed ancient Confucian texts. One of the leading neo-Confucian lixue proponents was the philosopher Zhu Xi (1130–1200), who claimed that an individual could understand the Way (or dao) through the study of principle, and in particular the moral principle operative in history.Footnote 41 By the beginning of the Ming period, Zhu Xi's interpretation of Confucianism became the backbone of the orthodoxy in which the state examination candidates had to train themselves. But from the sixteenth century a new school of thought represented by the statesman and philosopher Wang Yangming (1472–1529) challenged the idea that li [principle] could be found only in the Confucian classics. Wang, with reference to a saying of the fourth-third century BC Confucian exegete Mencius,Footnote 42 taught that all human beings were born with an innate “knowledge of the good” that would enable them to understand the Way directly, by trusting their own authentic or “genuine” feelings. According to Wang, “innate knowledge of the good” (liangzhi) could be tapped in each individual's mind, regardless of the person's social standing.Footnote 43

As numbers of late Ming intellectuals grew increasingly critical of the Zhu Xi version of neo-Confucian orthodoxy, they considered the relevance of Wang Yangming's teaching to contemporary tensions and problems. Wang's belief that the individual's own moral sense was the basis of ethics and social life inspired thinkers to critique everyday mores, and to search for ways to revitalize Confucian values.Footnote 44 They attempted to redefine neo-Confucian values in more human terms, and to invoke the concept of qing. Qing is a difficult term to translate in one simple word: it means feeling, emotion, sentiment, sensitivity, or passion, and can refer to “human emotional responses to particular circumstances”.Footnote 45 In contrast to the li of orthodoxy, which “represented stale didacticism, rigid dogmatism, and artificial regulation, qing signified the plain expression of fresh, natural, romantic and unsophisticated emotions”.Footnote 46

These efforts to recast Confucian values first became obvious in the work of Ming writers and playwrights, who fashioned a “cult of qing” that they communicated in vernacular literature and popular dramas which the printing industry churned out in great quantities, and about which readers and theatre audiences raved. In the plays of Xu Wei (1521–1593), for example, both the feelings and the physical bodies of the characters were unashamedly revealed – in one of the best-known scenes in his drama Kuang gulong [The Mad Drummer] the character Mi Heng reveals his “true moral mettle” to the well-known dictator Cao Cao (155–200) by shedding his clothes and appearing before him stark naked.Footnote 47 Attempts to accommodate qing to Confucian morality abound in short stories and plays that communicate the importance of sincerity and depth of human feeling in human interaction.Footnote 48

During the late Ming the “cult of qing” became immensely popular, and a means for men and women to explore the interplay of ethics and culture. The courtesan became a focal point of this examination. The sensuous side of her existence came to be perceived as the embodiment of qing, variously expressed as freedom and independence of spirit, courage and heroic action, detachment and understanding, true feeling and magnanimous spirit, and the overcoming of the boundaries between private and public spheres.Footnote 49 The connection between the marginality and dubious social station of the late Ming courtesan and her elevation as the symbol of refinement, high culture, freedom, and the possibility of actionFootnote 50 was observed by male admirers, who regarded her as the embodiment of qing. Courtesans appear in literature as models of loyalty, virtue, and courage, and often more so than the male characters.Footnote 51

Perhaps, the most eloquent spokesman of the late Ming discourse on courtesans and qing was the author Feng Menglong (1574–1646), whose writings brought the legally marginal courtesan to the “centre” of the Confucian moral universe. As someone critical of the polarities between high and low culture set by “respectable society”, Feng conveyed the “social underdogs” (petty vendors, fallen women, poor farmers) to the middle point of the literary world. He was an astute observer, and true to himself and his readers about what he thought morally right and truthful. Thus, he did not always idealize courtesans: his own honesty and sincerity also led him to write about manipulative ones who fooled their infatuated lovers with empty promises, as well as inconsistent ones who could not remain true to their vows of love.Footnote 52 In ideal (and allegorical terms), Feng perceived the devoted courtesan as a symbol of the unrecognized (male) talent who was denied entry into late Ming politics and forced to make a living in the cultural market, but whose authentic talents and qing would not be compromised or corrupted by the materialistic demands of the environment.Footnote 53

Feng Menglong's anthology of classical love stories, Qingshi leilue [A Classified Outline of the History of Love], interprets all phenomena in the human, supra-human, and sub-human territories from the perspective of qing, especially qing in the form of sexual love. In this compilation he treated courtesans as the ultimate challenge to orthodox norms of modesty and honesty. For example, in one of the stories in this collection he tells about men who tried every desperate means, including jumping over a wall, to avoid contact with the courtesans their friends had arranged for them to meet. Feng comments on this tale: “These were all people who were richest in emotions. They were earnestly worried that they might all of a sudden fail to control themselves; therefore, they took precautions and shunned the courtesans beforehand.”Footnote 54 At the end of this collection, Feng proposes the incorporation of virtuous courtesans into the pantheon of Confucian paradigms. He writes:

According to the teachings of the Spring and Autumn Annals [on the five principal classics], we should use the Chinese way to change the way of the barbarians, not use the way of the barbarians to change the Chinese way. Therefore, if a concubine harbors the virtue of a wife, then we should make her a wife; if a courtesan performs the deed of a concubine, then we should make her a concubine. Those who entrust themselves to their lovers for the sake of qing, I hereby acknowledge their qing. Those who sacrifice their lives because of genuine qing, I would be the last to suspect that their motivation may be impure. This follows the motto, “a gentleman takes delight in praising those who perform good deeds.” Otherwise, are we to say that menial laborers and offspring of concubines are not capable of bringing loyalty and filial piety in their nature to full play?Footnote 55

Here Feng brings into play the distinction between Chinese and barbarian and connects it to the virtue of chastity, implying that chastity was a Chinese female virtue, and thus to deny a lowly Chinese woman the opportunity to perform that Chinese wifely duty was to reject her Chinese identity and to turn her into a barbarian. With ethics and culture so intricately linked together, not to cultivate the morality of the marginal members of society could be viewed as making this periphery uncivilized, and that posed a threat to the integrity of Chinese culture. Courtesans, being at the bottom of gender and class hierarchies, symbolized the periphery of the periphery, and they therefore needed to be incorporated into mainstream Chinese culture.Footnote 56

Besides this male reading of the cult of qing, there was also the female appraisal of this phenomenon. As Dorothy Ko suggests, the cult engendered for the woman writer a new, positive image. Now, women could aspire to create literature as an expression of true self. “The marginality of women's words, irrelevant to any claims of formal political power, became the very source of their salvation.”Footnote 57Qing opened new doors for both courtesans and upper-class women. Conventional morality prescribed a wife's role to be fertile, chaste, and reverential – but now, in the late Ming, a certain “romantic equalitarianism” crept into the discourse of orthodoxy, and even marriage could be romanticized. By watching plays such as those by Tang Xianzu (1550–1616), whose 1598 drama “Peony Pavilion” told the story of a girl who falls in love with a young man in a dream and subsequently dies of longing, but returns from the dead after she appears in his dream and he opens her grave, and they are reunited,Footnote 58 women from all status groups fell under the spell of qing, and were captivated by eroticism and passion.

As such, while wives became more romantic, courtesans grew more legitimate. In entertainment quarters all over the empire, the courtesan's aura and artistic talents became all the more valued. In the early seventeenth century more and more courtesans entered the homes and the estates of the powerful, both as concubines and as “first wives”. Among the most celebrated unions of members of the male elite with brilliant courtesans were those of Qian Qianyi (1582–1664) and Liu Shi (1618–1684),Footnote 59 Mao Xiang (1611–1693) and Dong Xiaowan (1625–1651), and Gu Mei (?) and Gong Zhilu (1615–1673).Footnote 60

Figure 2 The well-known Ming courtesan, Gu Mei, depicted as an ascetic by the seventeenth-century painter, Zhang Putong. Original in Nanjing Museum; reproduced from Cass, Dangerous Women, colour plate 4. Used with permission.

Late Ming literatus–courtesan couples had a romantic idea that not only were they destined to marry each other but also that their life together would constitute an exemplary “wonderful tale that will last for a thousand autumns”.Footnote 61 It is also important to realize that both in public and private, late Ming courtesans emphasized their moral qualities, rather than their talent, among their admirers. While the late Ming courtesans began to see themselves as virtuous women, upper-class women tried to create a new self-image as “talented women” (cainü).Footnote 62 Within domestic spaces, courtesans and upper-class wives also now mingled in ways that were unprecedented: upper-class wives befriended courtesans by exchanging poems and paintings; wives invited “singing girls” to parties in private villas.Footnote 63

In the works of the elite women Xu Yuan (1560–1620) and Lu Qingzi (fl.1590s), many instances of artistic and emotional exchanges between them and courtesans were noted.Footnote 64 Xu Yuan, for example, made no secret of the fact that she was a great admirer of one of the most famous courtesans of her day, Xue Susu (1575–1652?), and published Xue's poems in her printed collection.Footnote 65 By the early seventeenth century it was no longer uncommon for both categories of women to have their poetry published in the same anthologies that were edited by both men and women.Footnote 66 These compilations convey both the celebration of the beauty, glamour, and elegance of courtesans as well as the talents of upper-class wives, along with their occasional envy of each other. Wives might have resented the courtesans’ relative freedom from domestic responsibilities and burdens.

The end of an era

By the time Zhang Dai had compiled his Taoan “dream memories”, he had already witnessed the cataclysmic fall of the Ming, which had originated in the combined turmoil of local rebellions and foreign invasion by the Manchus. The Manchus went on to establish the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), but they did not complete the unification of their empire until 1683, and thus political breakdown, warfare, and dislocation lasted nearly four decades. Men and women were astonished by the sudden overthrow of the Ming, pondered the causes of the dynastic collapse, and began to search for an explanation in terms other than Manchu military prowess. As Chinese men like Zhang Dai, who lost most of his material possessions (including his home), agonized over the causes, they increasingly came to the conclusion that the liberalism and “loose morals” of the latter half of the Ming dynasty were the primary causes of the debacle.

But before then, during the hectic period of dynastic disorder and fighting between rival forces, the expression of Ming loyalism became widespread, and courtesans were important agents of loyalist resistance. According to Kang-i Sun Chang, “after the fall of the Ming, the courtesan became the metaphor for the loyalist poets’ vision of themselves”.Footnote 67 The predicaments of both loyalists and courtesans were similar, locked in the futility of recalling a world that had collapsed, and resuscitating meaning in their shattered public and private lives.Footnote 68 On a practical level, courtesans – with their wide social networks and their itinerant lifestyle – could serve as scouts, messengers, and fundraisers;Footnote 69 over time, they earned a reputation as “inspiring” for their principled stand against the invader. Committing suicide in public as protest, many courtesans ended their lives as martyrs and suffered the ultimate sacrifice for their loyalty.Footnote 70

Gradually, however, the symbolic status of courtesans shifted – from representing the ideals of freedom, self-creation, and the possibility of heroic action – to that of a lost world of elegance, style, and grace.Footnote 71 The transformation in attitude towards courtesans, from one of culture and nostalgia to vulgarity and pity by the nineteenth century, may be attributed to several factors. First, in the years after the Ming downfall, a reversion to (Song dynasty) neo-Confucian orthodoxy on the part of Chinese scholars and male intellectuals set in, and adherence to ritual prescriptions became extremely important.Footnote 72 The revival of classicism in the Qing era hardened the line between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, making it more difficult for scholars to romanticize their relationships with courtesans. Secondly, the Qing takeover had destroyed many of the large fortunes of the Lower Yangzi region (where, for example, Zhang Dai had originated) and changes in the tax structure prevented the accumulation of the kinds of fortunes that had maintained the late Ming “good life”.

This situation may explain why, from the 1680s, publishers no longer rushed to produce new titles for upper-class “leisure reading”. The last major anthology of women's literature was printed in 1690, and the next one would not appear until 1773.Footnote 73 Also relevant is the new regime's growing control over printed materials, which led publishers to favour reprinting new editions of old, well-established texts rather than engage in new projects.

Another factor contributing to the downfall of the courtesan image was new government legislation with regard to palace entertainment. The Qing state banned female entertainers from official functions, which in the long run deprived courtesans of the security of their status and led to the expansion of private commercial entertainment giving new licence to pornographic sex markets.Footnote 74 At the same time, educated upper-class women appropriated the poetic genre, which had once been an integral part of courtesan literature. The wives and daughters of the scholar-elite distinguished their own erudition from the courtesan talents which they now trivialized.Footnote 75

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, courtesans came to be seen more and more as objects of pity and sorrow. Modern literary scholars have argued that Qing literatus and courtesan poems from that time place less emphasis on love, talent, glamour, or nostalgia, and more on the sufferings of courtesans from sexual exploitation, bondage, and shame. In the nineteenth century, the “vulgarization” of courtesan culture had become a fact. In 1818, Peng Huasheng, a chronicler of Nanjing's “flower houses”, had printed a handbook (which he sold for profit) to those in need of advice about attending these quarters. Ko sums up the contents of the guide, and its purchasers: “Not only did the courtesan turn out to be the shadow of her glamorous past, the scholar (client) was at best an impersonator of a literatus.”Footnote 76 Merchants and semi-literate traders had become the new patrons, while the women themselves were more likely to be illiterate and thus incapable of engaging in the arts and skills once expected of their Ming counterparts.Footnote 77

Concluding observations

One of the most important impressions that this examination of Chinese prostitutes and courtesans conveys is the changing dynamics of work and ethics in the late Ming period. Confucianism, which underwent a certain transformation in the sixteenth century thanks to the influence of Wang Yangming's thinking, impacted the ethos of both men and women. Despite an explicit legal code that denigrated both prostitutes and courtesans, both types of entertainer became enmeshed in the changing values of late Ming society and culture. Formally, neither kind of woman was prevented from improving her social station through her profession (or “work”). But it was the courtesan, with her sophisticated training and talents, that provoked the blurring of social strata and raised the question of what was most desirable in a good (liang) woman. The ancient Chinese system of “four commoner status” groups did not impede the demonstration of her abilities or the appreciation by both men and women of her “work”, i.e. the advancement of music, poetry, and painting. That the courtesan became the centre of a Confucian moral universe through the cult of qing was in itself an affirmation of the extent to which the values associated with Wang Yangming's philosophy had penetrated the lowest layer of the late Ming social order.

As we have indicated, however, the reign of the courtesan's golden aura was limited, to one brilliant period during the dazzling late Ming dynasty. Her magic did not endure, and eventually she became commoditized, like the Ming prostitute whose lifestyle and work reflected the ups and downs of market forces. The latter's path to liberation was usually concubinage, which provided at least the possibility of economic security and social mobility. The fall of the Ming and the institutionalization of the Qing did not change or affect her prospects in the long run. In contrast, for the courtesan, the Manchu conquest began the process of her vulgarization and aesthetic downfall.

The Ming defeat triggered political and identity crises for Chinese intellectuals, who sought salvation through their rehabilitation of the classical heritage and the cultivation of Confucian virtues based on the performance of ritual. By the end of the seventeenth century, they had created a social order broadly supported by a strict kinship organization that prized chastity and patriarchal values, and one that eliminated the role the prestigious courtesan had once held in Chinese society.