Ich schriebe fleissig, doch nicht ganz gegründet, bis ich endlich die gnade hatte von dem berühmten Herrn Porpora (so dazumahl in Wienn ware) die ächten Fundamente der sezkunst zu erlehrnen.Footnote 1

I wrote diligently but not in a well-founded way until, finally, I had the good fortune to learn the true fundamentals of composition from the celebrated Herr Porpora (who was at that time in Vienna).

One of the most important sentences in Haydn's autobiographical sketch of 1776 was for a long time the least understood. While other possible influences on the young Haydn (such as Johann Joseph Fux and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach) have frequently attracted the attention of Haydn scholars and still exert a strong influence on our idea of Haydn's education,Footnote 2 the encounter with Nicola Porpora – the only composer besides Dittersdorf that Haydn mentions by name in his autobiography – has not advanced beyond a small number of studies that do not collectively yield much insight. The notion put forward by various authors that Porpora gave Haydn a basic education in Italian and vocal technique, which was then reflected in Haydn's use of certain vocal idioms and figurations,Footnote 3 can be only half of the picture, since Haydn could hardly have regarded these things as ‘the true fundamentals of composition’. It is telling that Akio Mayeda, who pursues this hypothesis, has to conclude that one cannot ‘definitively trace a direct influence’.Footnote 4 Federico Celestini also concludes that it is ‘not possible to identify convergences in compositional processes between Porpora and Haydn’.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, neither author raises the question of how to interpret Haydn's remark about ‘true fundamentals’. Even James Dack's observation that Porpora exposed Haydn to the ‘current Italianate style in Viennese church music’ requires expansion and clarification if it is to explain precisely what Haydn learned.Footnote 6 The speculation advanced in The New Grove that ‘it may well have been at Porpora's instigation that [Haydn] systematically worked through Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum’ lacks any documentary basis; moreover, the rationale for this speculation – that Fux's Gradus is ‘the only work mentioned by any source that offers “true fundamentals”’Footnote 7 – is, as we shall see, entirely misleading.

In any event, the Porpora episode remains one of the least illuminated chapters in Haydn's biography, even two hundred years after his death.Footnote 8 Only the rediscovery and reassessment of the partimento and thoroughbass tradition in recent years has brought to light indications of what may have transpired between Porpora and Haydn in the Vienna of the 1750s.Footnote 9 In the following, I shall begin by summarizing the current state of partimento scholarship. I shall then analyse the sources that shed light on Porpora's relationship to the partimento tradition and Haydn's relationship to Porpora. Finally, by examining several music examples, I shall show what fresh perspectives a reassessment of the partimento tradition can bring to Haydn scholarship.

THE PARTIMENTO TRADITION

The historical, theoretical and pedagogical potential of Italian partimenti has in recent years awakened the interest of scholars in this important eighteenth-century tradition – what Robert Gjerdingen calls an ‘ingenious, widely disseminated, pre-industrial and non-verbal “technology”’,Footnote 10 which, as Giorgio Sanguinetti has argued, ‘contributed greatly to shaping eighteenth-century compositional technique’.Footnote 11 In Italian music theory, the term ‘partimento’ in its general sense refers to a figured or unfigured thoroughbass. In a more narrow sense, ‘partimento’ refers to the improvisational realization of such bass voices using a repertoire of voice-leading patterns. These schemata, which partimento students learn to apply above the given bass lines, consist primarily of the various types of cadence, the rule of the octave and numerous sequential progressions. The roots of these schemata can be traced back to the solmization and contrapunto alla mente processes of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.Footnote 12

The partimenti are closely associated with the academic tradition of the four Neapolitan conservatories, whose original mission was to train orphans for lucrative careers as professional musicians. In the eighteenth century partimenti developed into the core educational discipline of Italian music theory and, with the success of Neapolitan opera composers, spread among courts and musical centres throughout Europe – initially in nearly all other Italian musical and educational centres, and ultimately abroad as well. Paris and Vienna proved especially fertile ground for Neapolitan music theory (the curriculum for organists in Austria from the seventeenth century well into the nineteenth century is strongly influenced by partimento-like methods), but the partimento tradition left lasting traces in Germany too. The aim of partimento training was, writes Sanguinetti, an ‘(almost) unconscious act of composing’ that allowed the composer ‘simply [to] let his fingers “compose” for him in a quasi-automatic way’; ultimately, ‘among the students’ most impressive skills were not only the ability to compose with astounding rapidity but also the dexterity to emulate different styles convincingly, skills indispensable if one wanted to survive in the boisterous opera market of the eighteenth (and nineteenth) century'.Footnote 13 Counterpoint is also imparted through partimenti. Integrating imitations gives partimenti a noticeable contrapuntal complexity permeated by motivic processes: the culmination of the partimento curriculum is the partimento fugue.Footnote 14

HAYDN AND PORPORA

Nicola Porpora was without doubt a child of the partimento tradition.Footnote 15 Born in 1686 in Naples, the capital of partimenti, he entered the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo at the age of ten. It was here that he in all likelihood received instruction from Gaetano Greco. Other famous students to emerge from this conservatory include Leonardo Vinci, Domenico Scarlatti and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. It was probably in 1699, at the age of thirteen, that Porpora began himself to teach younger students as a maestrino (assistant instructor). Very recently a manuscript entitled Partimenti di Nicolo Porpora was discovered by Giorgio Sanguinetti in the library of the Conservatory of Milan.Footnote 16 While many partimenti in the manuscript's first part are attributed to different authors in other manuscripts, according to Sanguinetti the partimenti in the second part may well be by Porpora. They consist of rules, partimenti and a special version of the rule of the octave entitled ‘Scale invented by D. Nicola Porpora’.Footnote 17

In 1715, when Porpora became a maestro at the Conservatorio di San Onofrio, he had already composed a few operas on commission. He resigned this post in 1722 and made some initial attempts to establish himself outside of Italy, but returned to settle in Venice. The years 1733–1736 were spent in London. In 1747 he moved to the Saxon court of Dresden, where he first worked as a voice teacher and was later appointed Kapellmeister. Upon his retirement in 1752 the now sixty-six-year-old Porpora moved to Vienna, where the young Joseph Haydn came into contact with him through the librettist Metastasio.

Besides Haydn's autobiographical sketch quoted at the beginning of this article, the most important source of information on the Haydn–Porpora relationship is Georg August Griesinger's Biographische Notizen über Joseph Haydn (1810). Griesinger writes:

Through Metastasio Haydn also learned to know the now aged Kapellmeister Porpora. Porpora gave … lessons in singing, and because Porpora was too grand and too fond of his ease to accompany on the pianoforte himself, he entrusted this business to our Giuseppe. ‘There was no lack of Asino, Coglione, Birbante [ass, cullion, rascal], and pokes in the ribs, but I put up with it all, for I profited greatly with Porpora in singing, in composition, and in the Italian language.’Footnote 18

In Albert Christoph Dies's Biographische Nachrichten von Joseph Haydn, also published in 1810, the corresponding passage runs:

While Porpora taught the girl singing, Haydn, who had to accompany on the piano, found an excellent opportunity to gain a perfect knowledge and practical use of the Italian method of singing and accompanying.Footnote 19

Of further interest in this context is Dies's account of Haydn's reading of music theory textbooks after (or during) his time with Porpora:

But far from finding fault with Kirnberger's writings in general, I here set down Haydn's own opinion. He described them as a ‘basically strict piece of work, but too cautious, too confining, too many infinitely tiny restrictions for a free spirit’… . The second textbook Haydn subsequently bought was Mattheson's Der vollkommene Kapellmeister. He found the exercises in this book nothing new for him, to be sure, but good. The worked-out examples, however, were dry and tasteless. Haydn undertook for practice the task of working out all the examples in this book. He kept the whole skeleton,Footnote 20 even the same number of notes, and invented new melodies to it. Haydn now added to his library the textbook of Fux. He found nothing in it that could enlarge the scope of his knowledge; still the method, the approach, pleased him, and he made use of it with his current pupils.Footnote 21

Of course Haydn's (or his biographer's) disdain for the restrictions of contemporary textbooks is an act of (self-)stylization as an ‘original’ artist, unrestrained by the pettiness of contemporary theorists.Footnote 22 That Haydn at the same time admitted his respect for Porpora and his education indicates that he perceived practical, improvisational partimento training as less restrictive.

Haydn's early biographers agree that Haydn acted in the capacity of a répétiteur in the studio of Nicola Porpora. The arias and solfeggi that he accompanied there consisted in all probability of only the vocal part and an unfigured bass, the form in which Porpora's solfeggi – like many similar pieces in the Neapolitan tradition – have been passed down (see Figures 1a–1e). The playing of the unfigured basses, what Gjerdingen calls ‘musical pas de deux of solfeggio melody and partimento bass’,Footnote 23 is discussed in the third of the three early Haydn biographies, Giuseppe Carpani's Le Haydine:

Apprese però dal Porpora la buona ed italiana maniera di cantare, e quella pure d'accompagnare a cembalo; mestiere molto più scabroso di quello che si crede … Doveva accompagnare spesso le difficili sue composizioni, pieni di modulazioni dotte e di bassi non facili a indovinarsi… . Fondatosi ben bene nella teoria delle modulazioni e degli accordi.Footnote 24

Haydn learnt from Porpora the true Italian style of singing, and the art of accompanying on the harpsichord, an exercise much more delicate than is commonly supposed… . He frequently had to accompany Porpora's difficult compositions, full of learned modulations and basses difficult to work out… . He laid the foundations for the theory of modulation and chords there.

Figure 1

Nicola Porpora, Solfeggi fugati. Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Wien (Vienna) Ms VI 12834 (Q 3405). Used by permission

A letter written by the seventy-year-old Haydn shows that, even in later years, he regarded thoroughbass as an important musical and theoretical method:

Ihr Sohn ist ein guter Junge, ich liebe Ihn, hat auch Talent genug …, nur wünsche ich, das Er erstens den General Bass, dan 2tns die Singekunst, und endlich das piano forte Besser studiren möge, so versichere ich Sie liebster freund, daß Er durch fleiß und mühe noch ein großer Mann werden kann.Footnote 25

Your son is a good boy; I like him and he has talent enough …. I only wish that he would do better at studying first thoroughbass, then singing, and lastly the piano. In this way, I assure you, dearest friend, that, through toil and trouble, he can still become a great man.

This letter refers to the skills that Haydn had acquired a full half century earlier from Porpora. The combination of thoroughbass, voice and keyboard is crucial for the academic tradition of the Neapolitan conservatories, which relied on partimenti and solfeggi to impart the principles of voice leading and thus the fundamentals of composition.

Haydn's autobiographical sketch already provides an important clue in its use of the key word ‘fundamentals’: Fundament is frequently used in the southern German tradition of the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries to refer to improvisational and compositional training on a keyboard instrument.Footnote 26 The term Fundament in this tradition was, as Thomas Christensen writes, both ‘an empirical attribute of [the] lowest voice and harmonic substratum’ and ‘an ontological claim of priority and primacy as the foundation of musical composition and knowledge’.Footnote 27 One of the numerous examples from the eighteenth century is Fundamenta Partiturae by Salzburg Domkapellmeister Matthäus Gugl, which Haydn had in his music library.Footnote 28 Furthermore, Johann Sebastian Bach, paraphrasing Friedrich Erhard Niedt, considered thoroughbass to be ‘the most perfect foundation of music’ (‘das vollkommste Fundament der Music’), Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, the renowned teacher in Haydn's Vienna, spoke of the ‘Fundamental-Basis der ganzen Musik’, and in the preface to Johann David Heinichen's Generalbass in der Komposition – another title in Haydn's library – the author promises to relate the ‘fundamenta compositionis’, the fundamentals of composition.Footnote 29 Finally, there is the thoroughbass method entitled Partiturfundament by Haydn's brother Michael, in which only the unrealized bass lines have been proven to be by Michael Haydn; the realizations are additions by the editor, Michael's pupil Martin Bischofreiter.Footnote 30 A near-contemporary bibliography refers to Michael's Partiturfundament as ‘74 pages of partimenti’ (‘74 Seiten Partimenti’).Footnote 31

In the titles of such treatises, the term Fundament occasionally features the tautological addition of the German term gründlich.Footnote 32 In this context, Haydn's remark that ‘I wrote diligently but not in a well-founded way (nicht ganz gegründet) until, finally, I had the good fortune to learn the true fundamentals of composition (die ächten Fundamente der sezkunst) from the celebrated Herr Porpora’ is an indication of the compositional training on a keyboard instrument that Haydn received (probably more or less en passant) from Porpora.

It is not difficult to find further connections with the partimento tradition in Haydn's immediate cultural environment. Marianna von Martinez, Haydn's (and probably also Porpora's) pupil, writes in an autobiographical letter from 1773:

In my seventh year they began to introduce me to the study of music, for which they believed me inclined by nature. The principles of this [art] were instilled in me by Signor Joseph Haydn, currently Maestro di capella to Milord Prince Esterhazy, and a man of much reputation in Vienna, particularly with regard to instrumental music. In counterpoint, to which they assigned me quite early, I have had no other master than Signor Giuseppe Bonno, a most elegant composer of the Imperial court, who, sent by Emperor Charles VI. to Naples, stayed there many years and acquired excellence in music under the celebrated masters Durante and Leo.Footnote 33

In the catalogue of works by Bonno's successor as Viennese Hofkapellmeister, Antonio Salieri, a Libro di partimenti di varia specie per profitto della gioventù is mentioned, which is today considered lost.

PARTIMENTO COUNTERPOINT

There are various ways in which these insights can give new impetus to Haydn scholarship. First, they can do so through analyses based on the partimento tradition – concentrating on the actual bass line and the voice-leading schemata set above it. Following the custom of Viennese compositional theory as it persisted even into the nineteenth century, chords in this method are notated not with Roman numerals for a fundamental bass but with Arabic numerals for a real bass, which can then be specified through thoroughbass figures or indications of specific voice-leading patterns.Footnote 34 Since this feature of the partimento tradition has already gained some recognition,Footnote 35 we turn here to a less familiar area of partimento training: partimento counterpoint.

I am using the designation ‘partimento counterpoint’ as a pragmatic generic term for the various types of improvisational counterpoint on keyboard instruments. Compositionally, the primary distinction between partimento counterpoint and stylus a capella or prima prattica counterpoint lies in the key role played by prefabricated polyphonic complexes, sequential progressions and motivic repetitions. We cannot yet say for certain whether Haydn was first exposed to this tradition under Porpora or during his time as a choir boy – or even as early as in Hainburg. Teaching methods comparable to Italian partimenti are common in the Austrian organ tradition of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The techniques of improvisational counterpoint on keyboard instruments are found in the Compendium of Viennese court organist Alessandro Poglietti, for example.Footnote 36 The education that Haydn enjoyed at St Stephen's School has not been extensively studied. That Haydn was apparently able to work as an organist in the 1750s suggests a correspondingly early training.Footnote 37

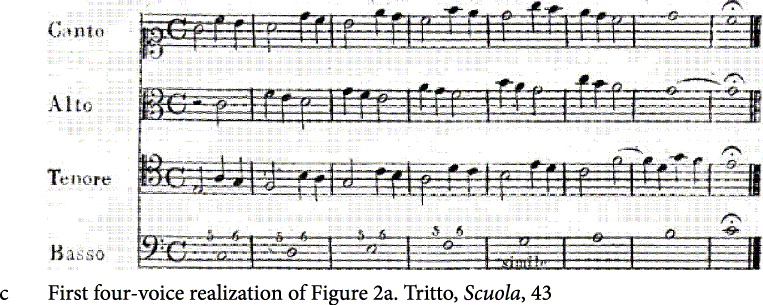

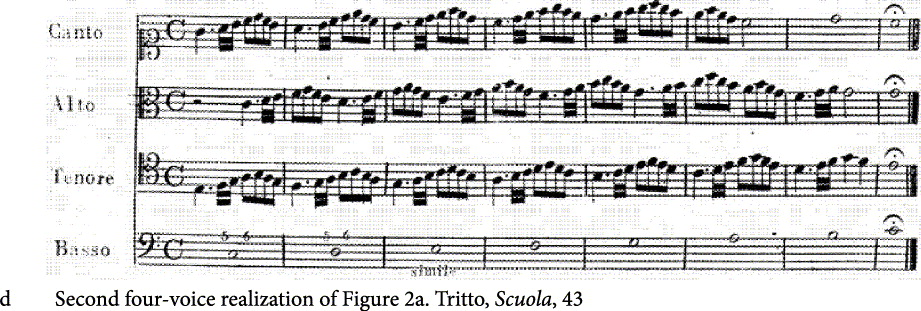

Partimento counterpoint involves the polyphonic figuration of schemata internalized by partimento students. Partimento counterpoint, William Renwick explains, ‘adds imitative counterpoint to the framework of pure voice leading, and … reflects a method of conceptualizing fugal composition and improvisation as an extension and refinement of thoroughbass’.Footnote 38 This is clearly illustrated in Scuola di contrappunto by Giacomo Tritto (1733–1824), for example. In this work Tritto summarizes the tradition of Neapolitan counterpoint as he had learned it in Naples in the 1750s (at the same time as Haydn's studies with Porpora).Footnote 39 Tritto's Scuola begins with an explanation of the typical partimento schemata. The maestro then explains the terms ‘fugue’ and ‘imitation’.Footnote 40 The student subsequently practises improvising fugues over given partimenti, developing a facility that relies on two tricks of partimento practice. First, the realizations of the bass lines are conceived as strict counterpoint above the bass in which each voice undergoes gradual motivic diminution. Partimento counterpoint belongs to the second of two classes of accompaniment described by Gregory Johnston: while other types of basso continuo were ‘vertically conceived and used to supply a full harmonic framework for monodies and concerted works’, the realization of partimenti was ‘linearly conceived and comprised what was essentially a literal transcription – or as close to one as possible – of a polyphonic composition’.Footnote 41 Tritto's realization of an ascending scale using the familiar ascending 5–6 progression makes this clear (see Figure 2, a–d).Footnote 42 Counterpoint emerges here through rhythmic-motivic ornamentation and increasing polyphonic figuration of a four-voice thoroughbass framework.

Figure 2

Realizations of partimento in Giacomo Tritto, Scuola di contrappunto (Milan: Artaria, 1816)

The second trick has to do with the insertion of canonic imitations. In his partimenti Tritto uses the word ‘imitazione’ to indicate places at which the player should imitate the bass with the upper voices. The imitative processes suggested by Tritto frequently entail certain sequential patterns that have been used by organists since the sixteenth century and are, as Renwick puts it, ‘ready-built to contain stretto or canonic passages, since they have an integral repetition structure’ (see Example 1).Footnote 43

Partimento counterpoint thus demonstrates a didactic and technical approach to counterpoint differing in many respects from species counterpoint, which, in the form of Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum, is usually regarded as paradigmatic for Viennese compositional theory of the eighteenth century. Peter Williams's assertion that ‘after the Bach period the language of music was taught less through practical work in “improvised” fugues (partimenti) and more through special exercises extracting pure intervals on paper (the species counterpoint taught by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and the later conservatories)’ is questionable.Footnote 44 Furthermore, the notion that thoroughbass-oriented compositional theory emerged in Protestant northern Germany and did not reach Vienna, with its focus on ‘Catholic Italian contrapuntal theory’, until the second half of the eighteenth century is refuted by the traditions of Italian and Austrian partimenti.Footnote 45 There is much to suggest that in Austria the tradition of improvised counterpoint on keyboard instruments was already important in the seventeenth century and remained so into the nineteenth century.Footnote 46 That Haydn was familiar with Fux's Gradus is well documented and cannot be disputed.Footnote 47 The precise role of this book and its didactics is not as obvious as it may seem at first glance, however (I shall return to this point later). It is, in any event, simplistic to limit eighteenth-century Viennese counterpoint to Fux. Any more accurate and detailed understanding of Viennese counterpoint should take the partimento tradition into account; the following thus draws upon several examples to illustrate how the influence of this tradition can be observed in Haydn's compositions.

HAYDN'S PARTIMENTO COUNTERPOINT

Analysis 1: Missa Sancti Nicolai (1772)

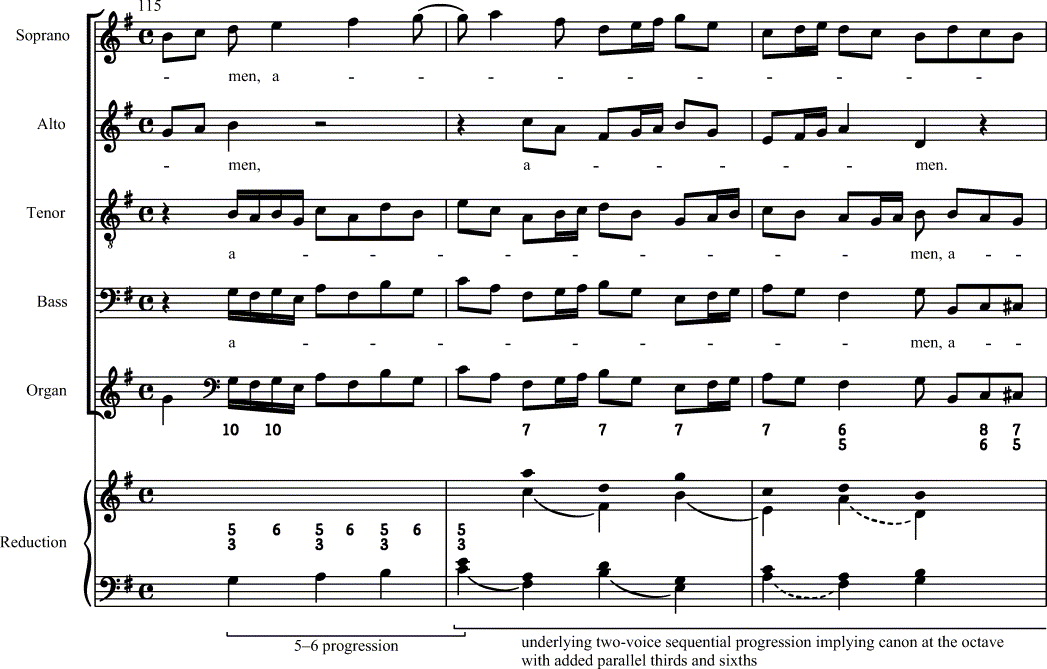

A very simple example of the influence of the partimento tradition can be found in a fugue at the end of the Gloria in Haydn's Missa Sancti Nicolai (see Example 2). In Haydn's autograph the organ part of this fugue is notated in the manner of a partimento fugue, where typically the entrance of every new voice is announced by its proper clef. The subject of this fugue is based on an ascending scale and harmonized by the 5–6 progression that was already explained above using Tritto's example. Short cadences are interpolated between occurrences of the subject. The avoidance of genuine four-voice writing in this fugue is itself an indication of its simple and improvisational character. The only place where it expands to genuine three- and four-voice writing is also based on the 5–6 progression, where the bass is doubled in thirds, and on the imitation technique of sequential patterns implying canonic structure, as demonstrated in Example 3. The two-voice canonic structure here (bass and alto) has parallel thirds/sixths added to both voices to create a four-voice structure.Footnote 48 This short fugue is based entirely on two contrapuntal tricks in the tradition of partimento counterpoint. Obviously, neither this fugue nor the following (nor any other fugue for more than one instrument) is a thoroughbass or partimento fugue in a narrow sense, since they are neither encoded (as a whole or in part) nor improvised during performance.Footnote 49 Rather, these fugues reveal a composer using the schemata he learned during his training in improvisational keyboard counterpoint; the extent to which Haydn reveals or conceals his improvisational models depends on the genre, the style and the complexity of the contrapuntal structure he strives to create.Footnote 50

Example 1 Stretto using sequential subject. Tritto, Scuola, 26

Example 2 Joseph Haydn, Missa Sancti Nicolai, Gloria, bars 108–114. Joseph Haydn Werke, series 23, volume 1b: Messen Nr. 3–4, ed. James Dack and Marianne Helms (Munich: Henle, 1999). Used by permission. Thoroughbass figures added here for clarification

Analysis 2: String Quartet Op. 20 No. 6 (1772)

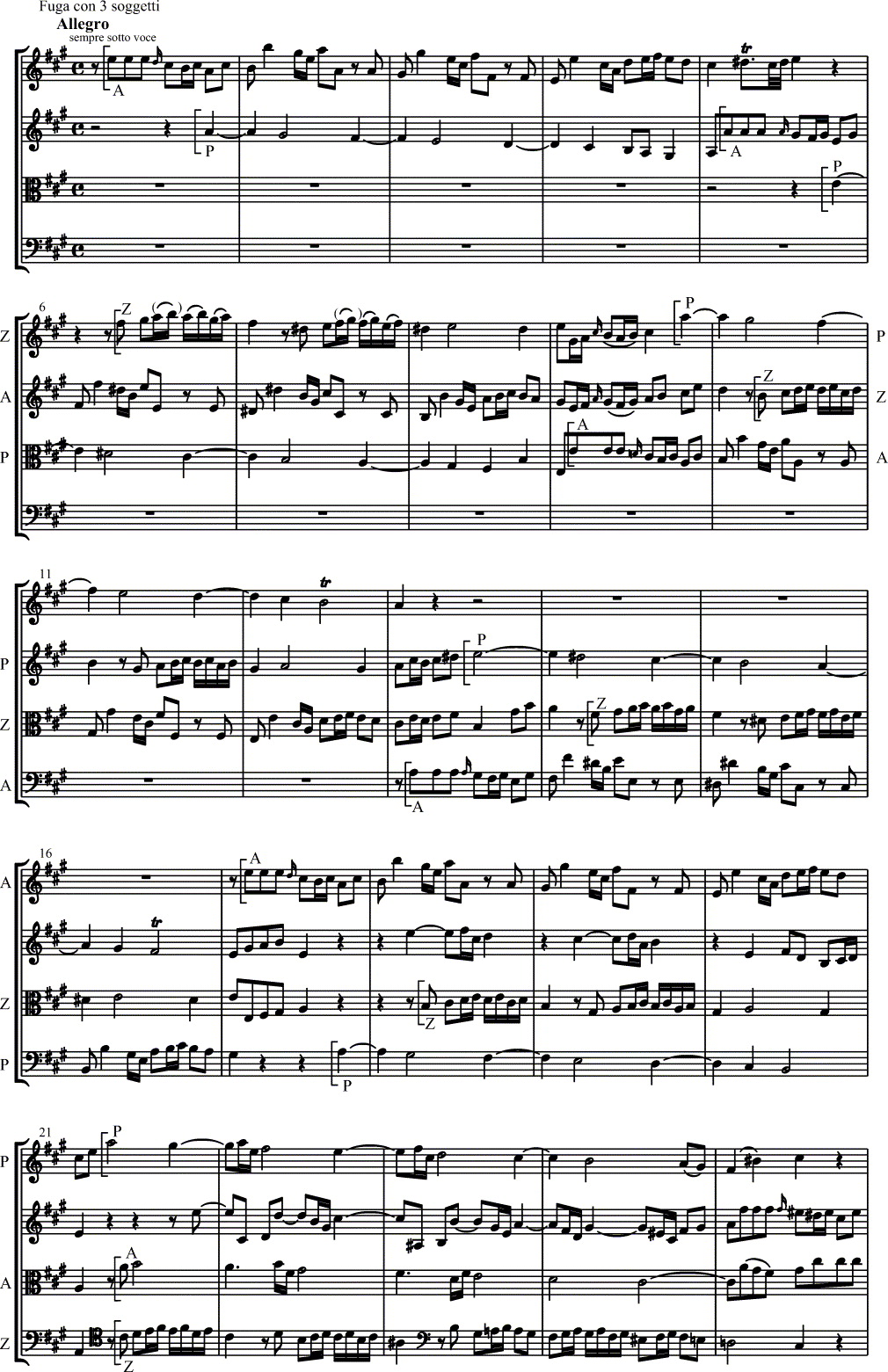

A more complex example, composed in the same year, is the fugue from Haydn's String Quartet Op. 20 No. 6.Footnote 51 Haydn referred to this fugue as a ‘fuga a 3 soggetti’; more precisely, it is a fugue in which the subject is supplemented by two countersubjects. Tritto, in his Scuola, explains the distinction between fughe col solo soggetto and fughe col soggetto e contra soggetto. The latter refers to fugues whose subject has an obligatory countersubject in invertible counterpoint that is introduced together with the subject. In 1805 (possibly in reference to Haydn's Op. 20) Honoré Langlé criticized the practice of calling such fugues ‘fuga a 2 soggetti’ or ‘fuga a 3 soggetti’: whereas a fugue with just one countersubject requires that the subject and countersubject be in invertible counterpoint, a fugue with two countersubjects requires that all three voices be in threefold invertible counterpoint.Footnote 52 Three-voice schemata in which the voices are freely combinable in a vertical arrangement present an easy way to invent such a structure.Footnote 53 In this fugue Haydn opts for a specific family of such schemata whose contrapuntal core is a descending chain of suspensions (see Example 4). Depending on which part of the syncope is in the lower voice, this can be a chain of suspended seconds or suspended sevenths (see Example 4a). The terms agens and patiens used in the following originate with Giovanni Maria Artusi and refer to the two voices that make up a suspension, one of them active in producing the dissonance, the other passive.Footnote 54 The suspensions at the second or the seventh can then be supplemented by an additional voice, referred to as Zusatzstimme (that is, extra voice) in the following.Footnote 55 The result is a three-voice model in which each voice can be the upper, middle or lower one, thus opening up six different possible combinations (see Example 4, b–d).Footnote 56

Example 3 Haydn, Missa Sancti Nicolai, Gloria, bars 115–117. Thoroughbass figures original

Example 4 Two-, three- and four-voice syncope in different inversions

Figure 3 reproduces illustrations of different members of this family of patterns from three methods of thoroughbass and partimento. Figure 3a, from the partimento method of Fedele Fenaroli, illustrates the interchangeability of the upper voices and adds a chromatic variant.Footnote 57 Figure 3b shows a diatonic three- and four-voice version in major and minor from Alexandre Choron's monumental Principes de composition des écoles d'Italie (c1808), a huge collection and translation of Italian partimento treatises covering three volumes and more than a thousand pages, in which ‘M. Joseph Haydn, à Vienne’ is registered in the impressive ‘Liste des Subscripteurs’, though he probably never received it.Footnote 58 Figure 3c is taken from the aforementioned partimento collection of Haydn's brother Michael. It is hardly a challenge to find this pattern, with all its inversions, in the solfeggi of Nicola Porpora that the young Haydn played during his time as a répétiteur. Figure 1c shows (in the middle of the system) a two-voice variant with the patiens as the lower voice. Figure 1d shows (at the beginning of the system) the Zusatzstimme as the lower voice. Finally, Figure 1e (again in the middle of the system) has the agens as the lower voice (with parallel tenths in the upper voice) and the patiens in the middle.

Figure 3a Fedele Fenaroli, Partimenti, ossia Basso numerato (Florence/Milan: Canti, 1863), volume 3, 4

Figure 3b Alexandre Choron, Principes des composition des écoles d'Italie (Paris: Le Duc, c1808), volume 1, 89

Figure 3c Michael Haydns Partiturfundament, ed. Martin Bischofreiter (Salzburg: Oberer, 1833), 21

From this three-voice pattern with its many possible combinations, it doesn't require much effort to produce a fugue with two countersubjects by extracting from the three constituent voices the three subjects, which can then be presented in all combinations without any further manipulation. This process can be found in the final movement of Haydn's String Quartet Op. 20 No. 6 (see Examples 5 and 6).Footnote 59 The compositional material and contrapuntal possibilities of this fugue are already sketched out in advance through the three-voice pattern and need ‘only’ be expounded upon in the composition. Haydn proceeds with great consistency here. At the outset of the fugue he systematically works through all six possible combinations. In the exposition he avails himself of just three of the six combinations (see Example 5, reading from top to bottom: Z–A–P, P–Z–A and A–Z–P). The modulating episode that follows (bars 21ff) is based on a fourth possibility (P–A–Z): with the underlying progression, it is easy to modulate by inserting accidentals at nearly any point. In the second thematic statement that follows (bars 28ff), Haydn uses the two remaining combinations (Z–P–A and A–P–Z).Footnote 60

Example 5 Haydn, String Quartet in A major, Op. 20 No. 6/iv, bars 1–25. Joseph Haydn Werke, series 12, volume 3: Streichquartette ‘Opus 20’ und ‘Opus 33’, ed. Georg Feder and Sonja Gerlach (Munich: Henle, 1974). Used by permission

Example 6 Haydn, String Quartet in A major, Op. 20 No. 6/iv, bars 1–4

It is clear that all the thematic statements in this fugue are based on one of the six possible voice combinations of this sequential progression. But what takes place in the other modulating episodes? They exhibit the same sequential progressions, which imply a canonic structure, outlined above (see Example 7). Haydn uses them as a modulating stretto of the theme, whose falling third fits easily into the progression used here.

Example 7 Stretto using sequential subject. Haydn, String Quartet in A major, Op. 20 No. 6/iv, bars 25–28 and 35–38

Analysis 3: Baryton Trio No. 114 (c1771–1778)

A chain of suspensions also characterizes the final fugue from Haydn's Baryton Trio No. 114 (see Example 8). The few elements besides this pattern that make up this fugue are pedal points (bars 70–74, 88–94) and cadences (bars 38–40, 81–88). Bars 28–32 also exhibit a progression used frequently by Haydn in which one middle voice remains static while the outer voices move in parallel tenths or thirteenths (see Example 9).Footnote 61 Bars 59–64 show another progression used occasionally by Haydn that is taught in many thoroughbass and partimento treatises (Figure 4 shows the corresponding excerpt from Partiturfundament by Haydn's brother Michael): ascending fifth progressions in the bass with 4–3 suspensions on every note, resulting in a chain of suspensions in the upper voices (2–6, 7–3, 2–6, and so forth; see Example 10).Footnote 62

Example 8 Haydn, Baryton Trio No. 114/iv, bars 1–12. Joseph Haydn Werke, series 14, volume 5: Barytontrios 97–126, ed. Michael Härting and Horst Walter (Munich: Henle, 1968–1969). Used by permission

Example 9 Haydn, Baryton Trio No. 114/iv, bars 28–32

Figure 4 Sequence of ascending fifths with 4–3 suspensions in upper voices. Michael Haydns Partiturfundament, ed. Martin Bischofreiter (Salzburg: Oberer, 1833), 21

Example 10 Sequence of ascending fifths with 4–3 suspensions in upper voices. Haydn, Baryton Trio No. 114/iv, bars 58–64

PARTIMENTO COUNTERPOINT AND SPECIES COUNTERPOINT

Susan Wollenberg has remarked that the opening of the fugue from this baryton trio looks ‘like exercises which a student might have produced while working from Fux's treatise [Gradus ad Parnassum]’.Footnote 63 It isthus surely worth inquiring into the relationship between partimento counterpoint and Fuxian speciescounterpoint, two traditions that, as Joel Lester puts it, ‘stood quite apart in underlying principles, pedagogical method and general philosophical outlook’.Footnote 64

It is well documented that Haydn read extensively from Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum and also used it in his own instruction.Footnote 65 The precise role this book played is, however, not at all clear. Were public professions of allegiance to Fux, as Lester has suggested, often just ‘lip service’?Footnote 66 Was Fux's work a textbook for a particular style or an introduction to the principles of voice leading for beginners? Important clues can be gleaned from the counterpoint didactics of the partimento tradition. Two different approaches to fugue were taken in the Neapolitan tradition, partimento fugue and vocal fugue, the first improvised, the second written.Footnote 67 Giacomo Tritto, at the end of his partimento-based Scuola di Contrapunto, suggests Fux's book as further reading, not as a textbook for the ‘fundamentals of composition’, but as quite the opposite: he recommends Fux (and Padre Martini's Esemplare Footnote 68) to students already familiar with the fundamentals on a keyboard instrument and with partimento fugue for further study in the art of counterpoint. It was in this spirit that the Salzburg organist Johann Baptist Samber added an extensive discourse on counterpoint to the end of his comprehensive thoroughbass method, on the grounds that the fundamentals of thoroughbass (‘die Fundamenta des regulirten Basses’) alone were not sufficient for a complete compositional curriculum.Footnote 69 In the same manner, the treatises on composition by Johann Friedrich Daube, written in Vienna during Haydn's lifetime, are built on the fundamentals of Daube's own thoroughbass method, which Haydn had in his library.Footnote 70 Padre Martini, the personification of what has been described as ‘Catholic Italian contrapuntal theory’, left a collection of partimenti that should also be regarded as the backdrop to his more famous book on counterpoint.Footnote 71 Furthermore, the documentation of Thomas Attwood's period of instruction with Mozart also shows that the lessons began not with species counterpoint but with exercises in realizing a given bass, and it is possible that these written assignments were just the supplementation of practical partimento exercises.Footnote 72 It is also known that Beethoven took extensive lessons from Albrechtsberger in species counterpoint at the age of twenty-four. It is hard to imagine that Beethoven – at that point already a fully trained organist, pianist, thoroughbass player and active composer – needed to study the fundamentals of voice leading: it is more likely that he felt the need to educate himself further in the prestigious stylus a capella, and Albrechtsberger was one of the most eminent of instructors for this.

All of these examples indicate that counterpoint in the general sense – the principles of voice leading, the ‘fundamentals of composition’ and their polyphonic figuration up to improvised fugue – was taught on a keyboard instrument in the partimento tradition. By studying Fux, the student acquired a specific contrapuntal language – the prima prattica tradition, the stylus a capella – that enjoyed great prestige, especially in Vienna, and whose products were still in demand in the Catholic-influenced state and ecclesiastical institutions of southern Europe.Footnote 73 Gradus played a symbolic role in this culture – indeed, it was a valuable piece of cultural capital – since it portrayed (in Latin) Hofkapellmeister Fux and his employer, Charles VI, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and dedicatee of Gradus, as successors to Palestrina and his employers, the Roman popes.

Nevertheless, Gradus ad Parnassum cannot be reduced to this style. Fux's book, when studied alongside practical training on a keyboard instrument, provides a theoretical basis for the voice-leading principles that also define partimento (prohibition of parallels and the different types of movement). Counterpoint in such a general sense (what Niedt called ‘the musical alphabet’Footnote 74) was indeed a prerequisite for learning thoroughbass, and most partimento treatises begin with a brief explanation of these principles. A book like Fux's also helped to make explicit the polyphonic structures implicit in partimento. The bass line alone is not enough to make explicit the contrapuntal relationship and the invertible counterpoint of the patterns illustrated in Example 4, for instance: what the player must read from the bass here is a tricinium in which a cantus firmus in minims is supplemented by one voice in the second species (two notes against one) and one voice in the fourth species (syncopatio). Friedrich Erhard Niedt expressed it thus: ‘To play thoroughbass means to produce proper counterpoint on a keyboard’ (‘Auf dem Clavier wird beym Spielen des General-Basses ein ordentlicher Contra-Punct gemacht’).Footnote 75 That is, a strict partimento realization could be characterized as species counterpoint over a cantus firmus in the bass,Footnote 76 but this view nonetheless overlooks the holistic, gestalt-like quality of partimento schemata that is so important for their practical purpose. Rather, the partimento player memorizes contrapuntal combinations haptically (that is, in large part through the sense of touch) and learns to apply them at the appropriate places over unfigured basses.

An eighteenth-century student could also return to Fux's book (or a comparable work) in a later stage of partimento training. Tritto, for example, is brief and pragmatic in his handling of imitation, fugue and canon; Fux's book is not necessary for a technical understanding of these things, but it gives them an additional theoretical and technical dimension, and endows them with the prestige of tradition.

Where the partimento tradition is not taken into account, however, there always remains a methodical problem, as Jen-yen Chen recently summarized (though without being able to offer a solution):

Gradus ad Parnassum … hardly offers sufficiently detailed discussion to permit modern historians an intimate understanding of how exercises in species counterpoint equipped one to write operas, symphonies and sonatas. The absence of such detailed discussion is perhaps a weakness of Fux's work, although numerous eighteenth-century composers successfully managed the transition without close guidance… . There remains the important question of how composers accomplished the shift from strict to free writing.Footnote 77

In a compositional education in which training on a keyboard instrument and training in the stylus a capella complement each other continually, this question does not present itself. We know that polyphonic keyboard music played an important role in Fux's own work as a teacher.Footnote 78 Fux was a student of the Austrian organ tradition, and many passages in his compositions exhibit progressions of partimento counterpoint – progressions, however, that appear in only very few places in his Gradus.Footnote 79 The problems that Lester describes with regard to Fux's book (the lack of practical instruction in dissonance treatment and diminution and the fixation on the old modesFootnote 80) disappear if one adds partimento tradition and partimento counterpoint as another piece of the mosaic of traditions that characterize eighteenth-century Viennese compositional theory.

Just as a productive coexistence and fusion of Ramellian basse fondamentale theory with the schemata of thoroughbass and partimento is characteristic of (Viennese) harmonic theory in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,Footnote 81 the Viennese counterpoint theory of this time draws from both Fux's species and the techniques of partimento counterpoint. An apposite example of this coexistence is the fugue from the finale of Haydn's Symphony No. 3 (see Example 11). The subject in long notes imitates the subjects of the stylus a capella. In the opening bars the subject is clearly accompanied in the style of the third species. But even this subject is based on a sequence progression, and by the time the stretto arrives in bar 91 it becomes clear why Haydn based his fugue on this type of subject: it lends itself wonderfully to canonic strettos, completely in line with the models of partimento counterpoint demonstrated above (see Example 12). So while the compositional foreground evokes the aura of stylus a capella and species counterpoint in its prominent passages, the polyphonic structure is designed from the outset for the sequential progressions of partimento counterpoint.

Example 11 Joseph Haydn, Symphony No. 3/iv, bars 1–9. Joseph Haydn, Kritische Ausgabe sämtlicher Symphonien, volume 1, ed. H. C. Robbins Landon (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1965). Used by permission

HAYDN'S CREATIVE PROCESS

Crucially, Haydn's relationship to partimento counterpoint not only opens new perspectives on the structure of his counterpoint, it also affords insights into the creative process. It is documented that Haydn frequently conceived his compositions in keyboard improvisation. Griesinger famously tells us:

Haydn always composed his works at the clavier. ‘I sat down, began to improvise, sad or happy according to my mood, serious or trifling. Once I had seized upon an idea, my whole endeavour was to develop and sustain it in keeping with the rules of art.’Footnote 82

Dies's description of Haydn's daily routine is similar:

At eight Haydn had his breakfast. Immediately afterwards Haydn sat down at the clavier and improvised until he found some idea to suit his purpose, which he immediately set down on paper. Thus originated the first sketches of his compositions.Footnote 83

Example 12 Stretto using sequential subject. Haydn, Symphony No. 3/iv, bars. 91–98

The idea of the ‘Amen’ fugue described above, for example, may have come to Haydn in a split second while improvising. The underlying idea of this composition derives from a specific sequence of pianistic hand positions. Or, to put it more aptly, the idea of this composition is a specific sequence of pianistic hand positions, which any player somewhat familiar with partimenti or thoroughbass can appreciate haptically by looking at the figured or unfigured bass line.

This haptical experience was described in the early twentieth century by Hugo Riemann, who had an intense love–hate relationship with Generalbass. On the one hand Riemann was squarely within the nineteenth-century tradition of what Ludwig Holtmeier has dubbed ‘thoroughbass-bashing’, part of Riemann's aggressive efforts to promote his own Funktionstheorie.Footnote 84 He regarded thoroughbass as practical stenography, a ‘practical school of accompaniment’, unsuitable as an ‘actual theory of harmony’.Footnote 85 On the other hand he penned an ardent plea for Generalbass lessons at conservatories, a plea in which Generalbass seems to return through the back door as the fundament of an applied, practical and haptical Musiklehre:

In recent times, physiologists and psychologists have related muscle responses to the hearing, reading and understanding of musical ideas. These muscle sensations are developed by the practice of Generalbass in the hands in a very curious way; a well-trained Generalbass player feels incorrect consecutives immediately in his fingers, which he can then forestall and thus implement the proper consecutives before his eye can correctly comprehend it. This is what I meant by my statement in the Vorrede of the first edition concerning the ‘four-parts streaming out through the fingers’ [‘Vierteilung des in die Finger überströmenden Willens’]. The meaning of this achievement for the composer, in addition to merely improvising at the piano, is obvious; from my teaching experience, I wish to add the fact that when silent examination of exercises produced with the pencil was utilized, this often impeded the process of muscle sensation that led to more immediate results.Footnote 86

An analysis drawing upon the tactile and technical experience of a partimento player taps into a realm that has seldom enjoyed truly convincing analysis: the integration of the body and of physical experience into music analysis. The schemata of partimento counterpoint derive from certain circumstances of keyboard playing. They form what Roger Moseley has recently dubbed a ‘vocabulary of touch … shaped by experience’, a ‘lexicon of expressions at an improviser's disposal’.Footnote 87 Chords, chord sequences and schemata are referred to in eighteenth-century organ-playing tradition as Griffe (fingerings, or hand positions): the improvisational keyboard counterpoint of the eighteenth century incorporates parts of the human body – the Griffe of the two hands.

Research into the compositional and improvisational training of the eighteenth century and the relationship of the two thus leads to the very core of the creative process: to the relationship between invention and elaboration, improvisation and composition, physicality and notation. The idea of writing a fuga a 3 soggetti based on a threefold invertible partimento pattern might have come to Haydn's mind while improvising at the piano, and while elaborating this invention; he might have felt it ‘streaming out through his fingers’ that one inversion of this pattern (with agens in the lowest voice) inevitably produces awkward ![]() chords (see Example 4b, bar 4, and Example 4d, bar 4). These

chords (see Example 4b, bar 4, and Example 4d, bar 4). These ![]() chords would have been tolerable in an improvisation or in simple pieces of improvisational character (the young Handel did not conceal them in the first of his Sechs kleine Fugen, based on the very same invertible three-voice schema). In a more ambitious, written-out fugue, however, they should be avoided (in Figure 1e we can see Haydn's teacher Porpora avoiding them by using simple parallel tenths instead of the Zusatzstimme, as described above). So, while elaborating his fugue (still at the piano or at his desk now), Haydn manipulated his subjects slightly: he inserted a rest in subject 1 (see Example 6, bar 2) and replaced one note of the Zusatzstimme in subject 3 by another rest (see Example 6, bar 3). Especially the first manipulation may be inaudible in practice, but on paper it avoids the

chords would have been tolerable in an improvisation or in simple pieces of improvisational character (the young Handel did not conceal them in the first of his Sechs kleine Fugen, based on the very same invertible three-voice schema). In a more ambitious, written-out fugue, however, they should be avoided (in Figure 1e we can see Haydn's teacher Porpora avoiding them by using simple parallel tenths instead of the Zusatzstimme, as described above). So, while elaborating his fugue (still at the piano or at his desk now), Haydn manipulated his subjects slightly: he inserted a rest in subject 1 (see Example 6, bar 2) and replaced one note of the Zusatzstimme in subject 3 by another rest (see Example 6, bar 3). Especially the first manipulation may be inaudible in practice, but on paper it avoids the ![]() chord that would have been a potential target for Haydn's critics, to whose arguments Haydn possibly responded with the fugues in his Op. 20 string quartets. Seen from this perspective, the rests mark a point between invention and elaboration, between improvisation and composition.

chord that would have been a potential target for Haydn's critics, to whose arguments Haydn possibly responded with the fugues in his Op. 20 string quartets. Seen from this perspective, the rests mark a point between invention and elaboration, between improvisation and composition.

An analysis drawing on Haydn's partimento counterpoint illustrates how the history of theory can rise to Christensen's challenge of ‘a critical new responsibility that far exceeds its charge as a custodian of tradition’, and how it can define ‘the very historical basis upon which present understanding – contemporary music analysis – takes place’.Footnote 88 Partimenti, whose spirit Haydn received from Porpora's hands, may prove to be the true fundamentals for a new understanding of Haydn.