It is the present aim once again to demonstrate emphatically that today's universal custom of performing Bach's cantata choruses with choral scoring throughout … sacrifices a multitude of fine and considered details to a craving for monumentality at any price.

Not my words but those of the eminent Bach scholar Arnold Schering, written some ninety years ago.Footnote 1 While ‘monumentality’ may be less prevalent today, the ‘continuously choral scoring’ to which Schering objected is still routinely promoted as Bach's own preferred practice. In this, the Mass in B minor differs not at all from the composer's other church works. Yet, in common with an overwhelming majority of those works, early sources for the Mass contain no suggestion whatsoever of any requirement for ripieno singers. (A brief reminder: the concertist, in contrast to today's soloist, was responsible for all choruses as well as solos, while the generally optional presence of a ripienist was simply in order to reinforce rather than replace the concertist in certain types of choral writing; see Appendix.) Both in the composer's autograph score of the complete Mass and in the set of parts prepared for Dresden, vocal tutti indications are entirely absent; moreover, neither this set nor that associated with C. P. E. Bach's 1786 Hamburg performance of the Credo – both apparently complete (with twenty-one and twenty parts respectively) – includes any copies for ripienists.Footnote 2 This conspicuous absence of direct evidence for vocal ripienists necessarily forms the starting-point for the present investigation.

Despite its unique (if problematic) status within Bach's output, the Mass in B minor has proved fertile ground for previous exploration of the composer's choral writing and its implied mode(s) of performance. Indeed, Joshua Rifkin's searching reassessment of the nature of Bach's choir was for some time widely perceived to relate almost exclusively to the Mass through his recording of the work, even though his original 1981 paper had barely made any mention of it.Footnote 3 In the same year, however, the Austrian-born American conductor Erich Leinsdorf specifically challenged (albeit in a much broader context) ‘the customary division of Bach's B Minor Mass into sections for full chorus and for soloists’:

For well over two hundred years it has been taken for granted that the solo voices sing only the arias and duets. Yet there is no indication whatever in the original score to justify the arbitrary divisions that have become almost universally accepted. … To anyone reading the score without preconceptions it appears quite clear that Bach assigned a considerably larger portion of the Mass to soloists.Footnote 4

(Leinsdorf proceeds to identify various ‘solo’ passages in Kyrie I, Et in terra pax, Cum Sancto Spiritu and Et resurrexit.) Behind Leinsdorf's thinking undoubtedly lies that of others, perhaps Wilhelm Ehmann's in particular, whose extensive work on the distribution of concertists and ripienists in the Mass first aroused my own curiosity in the matter.Footnote 5 Although Ehmann's contribution starts from the usual ‘choral’ standpoint and is marred by his emphasis on a proposed tripartite division of Bach's vocal forces – soloists, small choir (Chorsoli) and large choir (Ripieni)Footnote 6 – it nevertheless stands as a serious attempt to take the subject further. Much earlier still Schering, having noted evidence for ripieno participation in bwv21, 24 and 110, reached this conclusion: ‘Much more numerous [than this handful of unambiguous cases], however, are those instances where direct indications … are lacking but the “concertato” mode of performance must nevertheless be employed.’Footnote 7 The Mass in B minor, he points out, has ‘some classic passages’ where choral writing seems clearly intended for concertists alone, above all the continuo-accompanied opening of the Cum sancto spiritu fugue: ‘if it is executed by the solo quintet in the manner of many similar passages in the cantatas, there is then an elemental build-up from the chorus entry at “Amen” through to the repetition of the fugue by the full choir’.Footnote 8 (Schering's alertness here and elsewhere to the musical impact of these principles is well worth noting.)

Underlying this early recognition that choruses were not necessarily intended to be sung exclusively ‘chorally’ is the seemingly reasonable assumption of an ever-present larger body of singers (a ‘choir’) for whom choral writing is primarily designed. Rifkin's achievement, the product of a rigorous investigation of all the relevant performance material, has been to show just how fragile that assumption is and to recognize the central place that concertists occupied in the singing of choruses. With an ever-present team of solo voices (concertists), one for each vocal line, and perhaps the occasional option of additional singers (ripienists), the procedure is, from our perspective, simply the reverse of what had been assumed: rather than (re)allocating certain portions of choral movements to ‘soloists’, we need to ask exactly where – and (not least) whether – it might be appropriate to add vocal ripienists to the team of concertists.

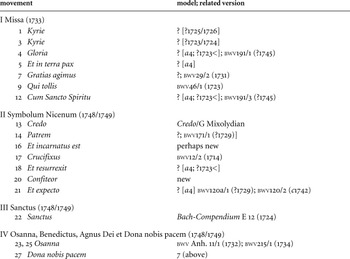

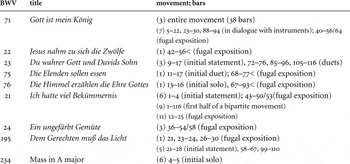

Lacking only chorales and turba movements, the Mass in B minor is a veritable compendium of Bach's choral writing and contains a higher proportion of choruses than the only two other works of comparable scale, the St John and St Matthew Passions. Of its sixteen choruses – eighteen if one includes the repeated Osanna and the return at Dona nobis pacem of the Gratias music – no more than two seem to have been newly composed (Confiteor and perhaps Et incarnatus), while of the earlier models all but one (for Crucifixus) may date from Bach's Leipzig years; see Table 1. Of particular value to this study are those nine choruses known in versions performed under Bach's supervision; see Table 2. In the circumstances it is scarcely surprising that none of the choral writing in the Mass, even if written with Dresden or some other musical centre in mind, appears to imply either vocal forces or conventions of vocal scoring that differ in any significant way from Bach's usual Leipzig practice.

Table 1 Choruses in the Mass in B minor

On this table the sign < means ‘or later’.

Table 2 Related choruses performed under Bach's supervision

* By analogy with bwv71, the wavy line () that appears from time to time at the foot of the page may indicate passages where ripienists might sing and/or where the organ's registration might be fuller (EBC, 37). See Rifkin, ‘Bach's Choral Ideal’ (2002), 59, note 111 (see note 26 below).

The principal aim of the present discussion is to explore the diverse implications of all this choral writing, with a specific view to establishing what role – if any – a vocal ripieno group might have played in Bach's expectations. Background information on the broader subject of Bach's choir, summarized and reviewed in the light of recent commentary and research, may be found in the Appendix.

A short preliminary test case serves to demonstrate the pitfalls of presuming a ‘choir’ (in the current sense) to be the intended vehicle of Bach's choral writing. In common with manuscript parts for well over a hundred other cantatas, the rare printed set for the Mühlhausen cantata Gott ist mein König, bwv71, includes none for ripienists.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, one might reasonably expect the performance of a large-scale early eighteenth-century work employing trumpets and drums and designed for an occasion of civic ceremony to be capable of incorporating a vocal ripieno body if suitable singers were available. bwv71 proves to have been no exception, as we learn both from Bach's autograph performing parts and from his outstandingly informative autograph score. Yet, as the composer himself specifies, the participation of the ripieno group is entirely optional: ‘se piace’. More important still, the ripienists are actually excluded from much of the choral writing. Far from giving them prime responsibility for all choruses, Bach limits their involvement to well under half the work's choral singing, calling on them only for sporadic appearances in two of the four choruses and for none whatsoever in a third.Footnote 10

This test case brings into focus two questions of overriding importance concerning ripieno participation in Bach's choral output as a whole, and hence in the Mass in B minor. Each proves significantly more fruitful than merely asking how many performers may have been available at Leipzig, Dresden or elsewhere:

1 How much in Bach's output actually demands vocal ripienists (as opposed to simply providing or allowing for them as an option)?

2 When ripienists are provided for, how exactly does Bach choose to deploy them?

While I assert above that ‘early sources for the Mass contain no suggestion whatsoever of any requirement for ripieno singers’, Christoph Wolff's edition of the work appears to tell us otherwise. At two points in the Dresden performing parts of the Missa the autograph inscription ‘Solo’ is found, against the alto's Qui sedes and against the bass's Quoniam. This, it is claimed, implies the presence elsewhere of a ‘vocal tutti ensemble’, which indeed it does. But to imagine that such an ensemble necessarily comprises more than one singer for each vocal line (Wolff promptly invokes the ‘three to four singers per part’ of Bach's 1730 ‘Entwurff’Footnote 11) ismere wishful thinking:Footnote 12 ‘all’ five concertists singing together also constitute a ‘tutti’, and the concertist's brief always includes the singing of tutti sections, whether or not ripienists are also present.

It might be argued that when a work lacked ripieno parts or failed to specify them in some way, it would have been entirely natural for a Cantor or Kapellmeister, at least on occasion, to have considered adding some. Just as certain acoustical spaces call for more violins than others, or for a stronger instrumental bass line, there are conditions in which it may at times be helpful to reinforce the vocal lines. More richly scored compositions or grander circumstances might also suggest the use of increased numbers of both instruments and voices: of the fifteen Bach works indicating ripieno participation, no fewer than eleven feature trumpet(s), the majority of them written for events outside the routine of Sunday worship.Footnote 13 Performance choices of this sort – unlike W. F. Bach's addition of trumpets and drums to bwv80 – leave the compositional fabric of a work intact and thus do not in themselves constitute arrangements or (arguably) even different versions of a work, merely different realizations.

And is this not exactly what today's performances generally do? By replacing (or at least expanding) the concertists' choir with a larger body of singers, are we not simply adapting Bach's rather modest forces in the very same spirit, perhaps to suit today's concert halls, while according these great works – through sheer admiration – a greater audible ‘status’ than their original circumstances may have merited? But there is, of course, a big catch to all this. Without due understanding of the conventions that governed ripieno writing, there will always be a distinct risk (to repeat Schering's words) of sacrificing ‘a multitude of fine and considered details’ to a desire for our own slimmed-down version of ‘monumentality’. Rather than allowing the composer's work to flourish in something like the manner he might have hoped for (if those are our aspirations), undue intervention – however well-intentioned – may inadvertently result in distortion.

With this in mind, we may set about the task of understanding Bach's own occasional use of ripienists,Footnote 14 in order to see what, if anything, might prove applicable – speculatively – to the Mass in B minor. In similar vein, George Stauffer asks: ‘If we … assume that Bach had at his disposal a modest-sized choir divided into concertists … and ripienists … , to what extent might he have used the former to create solo effects in the chorus movements of the B-minor Mass?’.Footnote 15 Setting aside any image this may evoke of a hypothetical single body of singers containing both concertists and ripienists, the question is more correctly put the other way around: to what extent might Bach have used ripienists to create fuller tutti sections in choruses?

A simple but fundamental principle underlies ripieno usage, and its importance can scarcely be overemphasized. A ripieno choir – a distinct body of singers whose function is to ‘fill out’ or ‘strengthen’ the vocal texture – ‘sings with’ or ‘joins in’ with concertists ‘only occasionally’ or ‘now and then’. These expressions, reminiscent of Johann Gottfried Walther's in his Musicalisches Lexicon oder Musicalische Bibliotec of 1732,Footnote 16 are all drawn from Johann Heinrich Zedler's Universal-Lexicon (1731–1754), where, for example, canto ripieno is defined as ‘a Discant for filling out [the texture], which joins in just occasionally’.Footnote 17 As surviving parts show, supplementary voices of this sort were not necessarily expected either to sing throughout choruses, or even to take part in all of them.Footnote 18 (At least one writer today nevertheless regularly misuses the term ‘ripieno’ simply to mean ‘the choir that sings choruses’.Footnote 19) Bach's own fairly consistent practiceFootnote 20 may be summarized as follows:

1) ripienists are likely to double concertists throughout in

a) chorales

b) turba choruses

c) stile antico and alla breve writing;

2) ripienists may be added at selected points in

a) concerto-like ritornello forms

b) fugues;

3) ripienists are likely to be excluded from

a) ‘solo’ passages

b) lightly accompanied passages

c) certain types of initial statement

d) affettuoso movements.

Before examining how some of these practices might influence our understanding of the various choruses in the B minor Mass, three interrelated questions must briefly be addressed. To what extent did such conventions vary from one town to another? Did court chapels operate quite differently from town churches? Is the process of extrapolation from a mere handful of works a reliable guide to what might have happened in others?

Despite differing local conditions, conventions of musical notation, composition, theory and practice were understood across (and beyond) German-speaking lands, as the circulation of music, books on music and musicians themselves attests. To answer the first question as it relates to ripieno practice, we may glance back at the subject of the test case above: Gott ist mein König, bwv71, written at Mühlhausen in 1708. Here, despite inevitable stylistic differences, there is little in the way the ripieno writing is handled that is not matched by Bach's later usage at Leipzig:Footnote 21

/1 As in the larger-scale rondeau structure of bwv23/3, the intermittent inclusion of ripienists serves to underscore the ‘motto’ theme of the movement's ABA`CA form.

/3 Comparison is not possible in this instance, as entire choruses where instruments other than continuo are not employed are very rare (one thinks of ‘Sicut locutus est’ in the Magnificat bwv243), and the group of works with known ripieno involvement contains no such movement. Here ripienists – like most of the instrumental ensemble – remain silent for the whole movement.

/6 Although marked ‘Affettuoso e larghetto’, the movement has clear stylistic parallels with chorale settings such as bwv76/7, where the vocal writing, usually doubled by instruments, is similarly homophonic. Ripienists double the concertists throughout.

/7 The fugue (bars 40–88) follows the familiar pattern whereby ripienists enter at the second exposition,Footnote 22 while in the flanking sections they are reserved for those few moments where most or all of the instruments are also engaged.

A second test case, while again touching on the matter of location, addresses the objection that musical practices at court chapels may have differed crucially from those of town churches.Footnote 23 Over the course of a decade Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis bwv21 travelled with Bach from Weimar via Cöthen (and Hamburg) to Leipzig, where the composer added ripieno parts.Footnote 24 In other words, at the court of Weimar (1714) and for the probable performance at one of Hamburg's churches (1720)Footnote 25 the cantata seems to have been performed in the same way: without ripienists. While some courts evidently used ripieno singers on a fairly regular basis, others did not, and from one town church to the next there was probably a similar diversity. Resources are not the issue here: ripieno voices were almost always considered optional, and musicians of the day knew how to deploy them if they were available and if they would benefit a particular work or performance. In the case of bwv21 Bach chose to use his added ripienists at Leipzig (1723) in all four choruses, but to different extents:

/2 Ripienists sing throughout.

/6 Concertists alone introduce both the first section and the fugue.

/9 A chorale tune in the first section of the movement is given to both concertist and ripienist tenors; the remaining ripienists join only later when instruments enter.

/11 The opening is sung by all, after which a fugue is led off by concertists.

More critical, perhaps, is the third question: can we safely second-guess the manner in which Bach might have chosen to add ripienists to his Mass in B minor? (There is, of course, no solid justification for assuming that he even considered the matter.) The discovery in 2000 of a set of ripieno parts to Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, bwv23, presented an almost unique opportunity to test earlier predictions, if only on a modest scale.Footnote 26 It comes as no surprise to find that ripienists ‘fill out’ the cantata's concluding chorale (/4) and that the duet passages of the chorus (/3) – which account for a good third of the movement – are left to concertists. But what is not anticipated in any modern edition of the work – and is not mentioned in Wolff's report of the discovery – is that the opening choral statement (bars 9–17) is also left to the four concertists. Having observed this feature of Bach's ripieno usage elsewhere – in bwv21/6 (1723) and bwv195/5 (c1742) – I had earlier hazarded a guess that here, too, ‘any ripieno parts would have begun [only] with the instrumentally doubled repetition of this phrase at bar 24’.Footnote 27 While this chance confirmation is perhaps of little consequence in itself (there is no comparable passage in the Mass), it reinforces the belief that ripieno practice in general and Bach's in particular merit closer attention than they have generally received. It suggests that careful extrapolation from Bach's own ripieno writing can go some way towards providing a reasonably secure framework for a better understanding of his choir. More specifically, it also suggests that in other respects, too, today's ripienists-with-(almost)-everything mentality may not accurately reflect Bach's own subtle understanding of vocal scoring.

It is well known that the choruses of the Mass in B minor are written variously in four, five, six and eight parts. This does not mean, however, that there are just four vocal scorings (with or without possible ripieno reinforcement). There are in fact six, as Bach's four-part writing appears in three forms: first with S1 and S2 sharing a single line, then with S1 tacet, and finally with the two four-part choirs singing together; see Table 3. (The first and last of these variants also occur elsewhere in Bach's output, both with and without the aid of ripienists.Footnote 28) These distinctions are easily overlooked, especially in today's conventionally choral performances. To hear (and see?) now four, now five, six or eight individual singers is inevitably quite different from experiencing all choruses tackled by a uniform body of choristers, generally with no more than a left–right division for the double-choir Osanna. And a distinctly richer experience, I would venture to suggest. The effect, if less monumental, is unquestionably more dynamic.

Table 3 Vocal scorings in the Mass in B minor

* At bars 21–24 of movement 12, where S1 and S2 are in unison, the writing is briefly a4.

Commenting on the total absence of tutti indications in the Dresden vocal parts for the Missa, Rifkin writes:

A scribe trying to extract ripieno parts from all this would have found it difficult indeed, especially in the absence of a score: at the very least, the task entailed a laborious collation of the parts already present. Hence, short of conjuring up a set of autograph ripieno parts left at Dresden but subsequently lost, we have no way of supposing that Bach envisaged more singers for the Missa than the existing materials allow for.Footnote 29

(As he also observes, ‘we know today that a performance of the Missa using exactly the forces that a strict reading of the Dresden parts would yield poses no practical difficulties.’Footnote 30) The circumstances of the later and larger Mass in B minor, for which there is no equivalent set of parts, are of course less cut and dried. Nevertheless, my aim is not to promote the use of ripienists in the work, let alone to prescribe their hypothetical use; rather, it is to help clarify the principles of Bach's own practice. After all, a good understanding of these principles can be the only basis for any serious speculation on the possible inclusion of vocal ripieno forces in performances of the Mass in B minor. Various general issues will be discussed as they arise in a survey of individual movements. To that end it will be helpful to consider the choruses under four broad stylistic headings: stile antico, concertato, concertato with fugue and (for want of a better term) affettuoso style; see Table 4.

Table 4 Choral writing in the Mass in B minor

STILE ANTICO

Composition in alla breve style or stile antico is well represented in the Mass in B minor. Although idioms of this sort stand in clear contrast to the younger concertato styles, they always coexisted with them. Thus we may look back, for example, to Giovanni Rovetta's collection of Salmi Concertati a Cinque et Sei Voci (Venice, 1626), which also includes two non-concertato psalms, marked ‘Per Cantar alla Breue con le parte Radoppiate Se piace’.Footnote 31 Here, as elsewhere, doubling of parts is specifically associated with alla breve settings, even though it remains strictly optional; for Rovetta's concerted psalms, on the other hand, it appears not even to have been an option. This conventional distinction in manner of performance was still drawn in Bach's Germany (see Appendix), and the underlying reasons are succinctly articulated by Walther when he chooses ‘da Capella’ writing, with its avoidance of small note values, to exemplify a compositional style that is appropriate ‘if many voices and instruments are to do one and the same thing accurately together’.Footnote 32

/3 Kyrie The explicit presence of ‘Stromenti in unisuono’ makes it a natural candidate for the optional addition of ripieno voices. With S1 and S2 assigned to a single vocal line (as in /7 and /14), the soprano line is indeed already reinforced.

/7 Gratias agimus Again, S1 and S2 share a single vocal line. The continuous colla parte instrumental doubling of the vocal lines would also seem to allow further doubling by ripieno voices, as suggested by the ripieno parts to Wir danken dir, Gott, bwv29/2 (1731). The music's return in another guise, however, raises some questions (see /27 below).

/13 Credo in unum Deum According to The New Bach Reader Carl Friedrich Cramer (1786) expressed the opinion that in performing ‘the five-part Credo of the immortal Sebastian Bach … the vocal parts must be presented in sufficient numbers [hinlänglich besetzt], if it is to show its full effect’.Footnote 33 Not for the first time we encounter a translation that reflects a critical preconception rather than the original text. Cramer's report of C. P. E. Bach's Hamburg performance continues: ‘Our good singers proved again, especially in the Credo, their known skill in performing securely the most difficult passages.’Footnote 34 As Rifkin has shown, the ‘staunch’ (brav) singers in the Credo are most likely to have comprised five of Emanuel's usual team of eight (just five copies were prepared), while Cramer's admiration of their ‘skill’ in undeniably ‘difficult’ music most naturally relates to his immediately preceding remark that the vocal parts be ‘assigned adequately’ (hinlänglich besetzt), that is, given to suitably capable singers. Certainly, there is no mention of ‘numbers’, and it rather looks as though commentators and translators may have confused quality with quantity.Footnote 35

Yet at Hamburg, as many will be aware, C. P. E. Bach did choose to reinforce the vocal lines with instruments, both here and in the Confiteor. George Stauffer has proposed that these two movements belong to a tradition in which instrumental doubling was routinely added.Footnote 36 There are, nevertheless, good reasons for not viewing this first movement of the Credo in the same light as, for example, the Gratias / Dona nobis pacem – not least the absence of any notational warrant for colla parte instrumental doubling. In addition, by holding a full, independent instrumental accompaniment in reserve, Bach is surely creating a forward momentum from this movement to the Patrem omnipotentem that is only dulled by employing fuller forces at the start. (This cannot be disregarded merely on the basis of a perceived similarity to ‘a nineteenth-century-oriented crescendo’.Footnote 37) Begun – even before the continuo enters – with a single voice as by a celebrant, the Credo's intended progress to an eventual tutti could scarcely be more palpable (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

There are also grounds of a less subjective nature for believing that ripieno voices would have been considered inappropriate in the Credo in unum Deum – and these have implications that reach far beyond this particular movement. The first dozen or so bars, as we can see, lack any instrumental accompaniment beyond that of the basso continuo, and even the contrapuntal lines subsequently given to the violins cannot be considered as accompanimental to or supportive of the voices in any usual way. In effect, the movement consists of seven equal ‘voices’ (the two highest necessarily instrumental) over an independent bass. The question raised is this: does choral writing in which the instrumental ensemble is silent (or, as in this exceptional case, only partially involved and in an atypical fashion) ever attract ripieno voices in Bach's output? Just as instrumental doubling of one sort or another is a valuable guide to the plausibility of possible vocal reinforcement, is the absence of such instrumental support an indicator that concertists were expected to be left untrammelled by additional voices? The fifteen works with known ripieno involvement give a fairly clear answer: extended passages – let alone entire movements – where ripienists sing but the instrumental ensemble is silent are conspicuously absent. And what seems to be easily Bach's longest stretch of writing for more than one voice on a part with continuo only comes from elsewhere: the exceptionally turbulent opening sixteen bars of ‘Sind Blitze, sind Donner in Wolken verschwunden’ in the St Matthew Passion, bwv244/27b. These meagre statistics are set out in and may be compared both with bwv71/3, a complete thirty-eight-bar movement explicitly intended for just four singers, and with other similarly telling examples given in Table 6.

Table 5 Choral passages for more than one voice per part with continuo only

On this table the sign < means ‘slightly fewer than’ when placed before the numeral, and ‘slightly more than’ when placed after.

Table 6 Choral passages for concertists and continuo alone in works employing a ripieno

On this table the sign < means ‘and over the next few bars’.

/20 Confiteor See below.

/27 Dona nobis pacem At its second appearance the vocal scoring has subtly shifted to take account of the three voice parts first added at the Sanctus (A2, T2 and B2). Thus it is now not only the top vocal line which is doubled (with S1 and S2 in unison, as before), but each of the four: A1 with A2, T1 with T2, and B1 with B2. The ‘discrepancy’ between the two vocal scorings of the same music may be viewed as a mere notational nicety resulting from Bach's shift from the predominantly five-part vocal texture of the Kyrie, Gloria and Credo to the six and then eight parts of the Sanctus and Osanna. As such it may appear to be of little practical consequence, in that the addition of ripienists for the Gratias would have been regarded as a perfectly conventional option which (assuming a conventionally small number of ripienists) would have made only a modest difference to the texture. Alternatively, the distinction could be seen as entirely purposeful on Bach's part, implying just the expected five singers for the Gratias and then eight for the Dona nobis pacem, as a means of creating a cumulative effect for the conclusion of the Mass.

STILE CONCERTATO (I)

/4 Gloria Bach's use of the same material in bwv191/1 dates from just three years or so before workon the complete Mass in B minor began. No parts survive for the cantata, and, unlike the last movement (= /12 Cum Sancto Spiritu; see below), the first contains no hint of ripieno involvement in the autograph score. (Any conjectural ripieno parts reflecting Bach's own practice elsewhere would most probably have to exclude at least the brief introductory duets at 25–28 and 41–44 and the four successive entries at 69–76.)

/18 Et resurrexit One feature of this movement demands particular attention. At the words ‘Et iterum venturus est’ the bass part is given an extended twelve-bar ‘solo’ – except that nowhere is the passage actually marked solo, nor are there any complementary tutti indications. Multi-voiced renditions are still heard in some of today's period-instrument performances, yet most scholars and performers (if not all bass choristers) probably acknowledge that the passage is really intended for a single singer.Footnote 38 Similar ‘soloistic’ bass writing in bwv195/5 (from Dem Gerechten muß das Licht) may be seen to support this: at bars 72–78 the corresponding ripieno bass part (c1742) is given rests. Unless Bach's notation in the Mass is to be regarded as deficient, the straightforward inference is that the whole movement (and indeed the entire work) is also intended – at least primarily and essentially – for single voices. (Bars 9–14 and 93–97 have no obvious parallels in Bach's ripieno parts, and as a general rule any movement that does not clearly suggest where ripienists might and might not sing is likely to be one in which their participation was not anticipated.)

/21 Et expecto Related sources shed no light on possible ripieno usage in this movement. Passages that are accompanied by no more than continuo – and occasional flutes (bars 17–24, 41–49, 61–69) – lack any real precedent for ripieno doubling (see p. 19 and Table 5 above).

/23 (and /25) Osanna in excelsis Surviving parts for Bach's earlier use of this music in Preise dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen, bwv215/1 – apparently a complete set – include just a single copy for each of the eight vocal parts (2 x SATB). Moreover, the strong possibility that the second choir in the St Matthew Passion originated as a one-to-a-part ripieno choirFootnote 39 suggests that of all choruses in the Mass this is perhaps the least likely to have attracted ripieno doubling.Footnote 40

STILE CONCERTATO (II) WITH FUGUE

In fugues, Schering tells us, ‘Bach often reserves the instruments for the entry of the choral voices’.Footnote 41 Several decades earlier, however, Wilhelm Rust had more correctly put it the other way round: Bach's ripieno parts show that his common practice in fugues was to hold back these extra voices until the instruments enter at the second exposition, thus leaving the first exposition to concertists and continuo alone.Footnote 42

/1 Kyrie Questions of vocal scoring present themselves even in the very first two bars of the Mass. If we first compare S2 in bar 1 with the doubling wind parts, and then S1 in bar 2 with the corresponding wind parts, we must surely ask why the rising figures on ‘e-[le-i-son]’ are left to the respective voices, undoubled. An undoubled vocal ensemble of concertists renders these pregnant phrases – effectively and affectingly – as solos. With additional singers, the choice is either to create ripieno parts that match the doubling instruments (leaving the three-note figures to the concertists) or, questionably, to treat the phrases as brief, if conspicuous, choral ‘solos’.

Similar apparent ambiguity confronts us in the spacious fugue that follows. By any reckoning the first four fugal entries, which are free of instrumental doubling, must be considered as intended for concertists alone. But the fifth entry (for bass voice at bar 45) confuses the picture, in that it is supported not only by continuo but by viola and appears to do double duty as the first of another set of similar leads. If we are to introduce a ripieno bass, the temptation would be to do so here. However, this would not only deprive the concertist of his anticipated ‘solo’ entry, it would set up the expectation of ripieno entries in all voices, when in practice no appropriate entry points exist for tenor and alto at this stage in the movement. At the next set of entries (from bar 81) no such problems arise, despite the unusual absence of instrumental doubling for the tenor line. Only for the second half of the fugue would the hypothetical involvement of ripienists make sense.

/5 Et in terra pax In the fugal writing the situation here is relatively clear-cut: the first exposition (bars 20–37) leaves the subject free of instrumental doubling and keeps the accompaniment light, whereas the second exposition (bars 43–60) is consistently doubled by instruments and would therefore admit similar vocal doubling. As for the ritornello elements of the movement, there are no such clear guidelines – reminding us that none of these ‘problems’ need exist if we accept that Bach's writing does not actually require a ripieno.

/12 Cum Sancto Spiritu In the autograph score of the related bwv191/3 a wavy line () appears from time to time at the foot of the page. A similar line in bwv71 appears in conjunction with the word ‘Capella’, seeming to indicate passages where the vocal ripieno joins the concertists.Footnote 43 In the case of the Cum Sancto Spiritu it would not be the usual straightforward matter to create satisfactory ripieno parts, whether a5, following the existing scoring, or a4, following both the conjectured original scoring and the conventional composition of ripieno groups. On the other hand, it is tempting to imagine Bach himself doing so with relish, as the placement of the line in bwv191/3 clearly has some musically strategic purpose. (The absence of the line at the equivalent of bars 81–105 nevertheless points more towards its being a possible guide for a bassoon part.Footnote 44) On the principle outlined above, the fugal section at bars 37–64 (now without bwv191/3's light instrumental accompaniment) would in any event preclude ripienists.

/14 Patrem omnipotentem As in /7, S1 and S2 sing in unison, meaning that the soprano line is already doubled. Here, though, the instrumental doubling of vocal lines is both fluid and intermittent. Unusually, all fugal entries (with the common exception of some in the bass part) are supported by instruments, which would make ripieno reinforcement more plausible than in many other places, especially following a concertists-only Credo in unum Deum (see p. ooo above). Differentiated ripieno parts do not readily suggest themselves, and no original performing material survives for the related bwv171/1 to help us in our speculation.

/22 Sanctus In its earlier independent form (scored for SSSATB rather than SSAATB) the Sanctus survives in a full set of parts with just one for each of the six voices.Footnote 45 The writing at the opening is in any case far too subtle to lend itself to any straightforward ripieno doubling, and at the ‘Pleni sunt coeli’ a twenty-four-bar stretch with ripienists but no instruments other than continuo would be unprecedented (see p. 19 and Table 5 above).

AFFETTUOSO STYLE

/9 Qui tollis Bach's model for this movement, bwv46/1 (Schauet doch und sehet), dates from his first summer at Leipzig and from a month or so after he evidently ceased providing ripieno copies on a regular basis; the surviving set of parts – quite possibly a complete one – includes none for ripienists. For the four-part writing of /3, /7 and /14 Bach brings his two soprano parts together on a single line; here he does not. The most uncomplicated explanation for this is that the intimate character of the vocal writing (marked p in bwv46/1) would simply be diminished by anything more than the occasional doubled phrase in one or other string part. The particular expressiveness demanded by both text and music lies naturally in the province of solo voices.

/16 Et incarnatus est Individually and collectively, the spare accompaniment (just unison violins and pulsating bass line), the intensely expressive vocal lines and the tortuous harmony all suggest that ripienists would not merely be redundant but would prove an encumbrance to the concertists. When at the end, with the reduction from five- to four-part writing for the ensuing Crucifixus, one singer drops out from a five-person ensemble, the effect is distinctly more potent than any corresponding reduction in conventional choral numbers.

/17 Crucifixus Here, too, and for similar reasons, there are no real grounds for considering ripieno participation. At Weimar, where Bach first used this music more than forty years earlier, in bwv12/2 (Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen), a ripieno group does not appear to have been much used.Footnote 46 The extant performing material for the cantata comprises only a basso continuo part and a set of four parts for concertists.

/20 Confiteor It may be unexpected to see this extraordinary movement, the only incontestably new composition in the whole Mass, grouped here with the Qui tollis, Et incarnatus est and Crucifixus settings. In five rather than four parts, it is rigorously contrapuntal in nature and with no instrumental accompaniment other than continuo. Where Stauffer again argues for the addition of colla parte instruments (as well as the ripieno voices he presumes),Footnote 47 I would strongly suggest the opposite approach: that nothing more is implied than a five-part ensemble of concertists with continuo, and that this is exactly what J. S. Bach intended – even if one of his sons took a different line some forty or more years later (see p. 18 above). Several reasons may be given. We have seen the evident care Bach took in assigning the soprano part in four-part writing (not just to ‘soprano’ but to S1 and S2 together, or to S2 alone); to have made no mention of colla parte instruments, let alone of how they should be distributed, would by contrast have been a major oversight. While instrumental doubling might in principle suit the fugal writing and its plainchant cantus firmus, its continued use in the ensuing highly charged Adagio (‘Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum’) would surely be counterproductive. One of the miracles of the Confiteor is the manner in which this new section emerges from the fading counterpoint. The removal of instrumental doubling at any point during this transition would be an unwelcome distraction, and the only plausible place for this to happen would be bar 123, two bars after the Adagio has already begun.

bwv71/3, ‘one of the few purely vocal Bach cantata choruses’,Footnote 48 provides a perfectly sound model for entrusting an entire movement of this sort – where the instrumental ensemble rests – to concertists alone (see p. 19 and Table 5 above). Put another way: there is no known instance of ripienists taking part in this admittedly rare type of chorus. Earlier I cited the parallel scoring of bwv243/11, the ‘Sicut locutus est’ from the D major Magnificat. The movement also offers a parallel context: just as Sicut locutus est (another fugal movement notated in 𝄵) prepares the way for the tutti Gloria, so too does the Confiteor lead us dramatically into the tutti Et expecto. Maximum contrast of scale between adjacent movements is surely intended. Just as Credo in unum Deum and Patrem omnipotentem form a stile antico – stile moderno pair, so do Confiteor and Et expecto. From this Stauffer proceeds to argue that in order for the two styles to appear on ‘an even footing’ and equally ‘important’, they should sound comparably ‘weighty’, producing ‘a symmetrical plenum sound closer to Baroque convention’.Footnote 49 This, it seems to me, again confuses quality with quantity and hints at a familiar underestimation of the sheer excellence in ensemble singing that will have been expected, for example, from Dresden's top five Italian singers.

One final reason for ruling out ripienists from the Confiteor relates to a notable feature of the Adagio – the enharmonic C/B♯ in the first soprano part (bars 138–139). In 1786, the year of his Hamburg performance of the Credo, C. P. E. Bach wrote:

Sänger können so wohl als Instrumentisten rein singen und spielen, aber bey enharmonischen Fällen ist es beynahe unmöglich, daß, zumahle wenn mehrere zusammen sind, alle auf einen und den gehörigen kleinen Punkt des Intervall rücken. Ein Ausführer, oder viele machen einen großen Unterschied hierin.Footnote 50

Singers are just as able to sing in tune as instrumentalists are to play in tune, but in enharmonic contexts it is well nigh impossible, especially with several together, for everyone to hit the same precise interval that is required. One performer or many makes a big difference in this respect.

How this observation might relate to his experience of performing the Confiteor is anyone's guess. Pace Fux (1725), who regarded colla parte doubling as appropriate to chromatic and modulatory writing,Footnote 51 my own strong suspicion is that Bach père, rather than adding another ‘full’ chorus to the work, was drawing on the unmatchable potential of a good team of concertists for suppleness and expressivity – and fine tuning. To ignore this by adding either instruments or (second-rank?) voices risks flattening out, rather than enhancing, the magnificent array of vocal scorings and textures that comprise Bach's Mass in B minor.

While the 1733 Missa is preserved in a carefully prepared set of performing parts, the autograph score of the complete Mass necessarily leaves many more performance issues open. If the work's sheer length and grandeur tempt us to explore what an unspecified vocal ripieno group might bring to a performance, we must surely start with a thorough understanding of how Bach himself might have approached the matter – but also with a clear awareness that he might well have regarded the exercise as merely incidental, even pointless or perhaps utterly undesirable. This awareness might in turn edge us just a little closer towards understanding Bach's B minor Mass.

APPENDIX

In reviewing some of the broader underlying issues, and for ease of reference, I indicate those chapters in The Essential Bach Choir (EBC) where topics are addressed at greater length, and draw attention (by underlining key words) to various sources of information introduced here for the first time.

Repertories (EBC, 17–27) Chant, chorales, motets and concerted church music formed a hierarchy of distinct repertories, of ascending technical difficulty. At Leipzig Bach allegedly considered it ‘beneath his dignity’ to be required to direct mere chorales, while motets – drawn from an anthology already over a hundred years old – were routinely left to the prefect. Cantatas could be ‘as hard again’ as motets, and Bach himself tells us that his own music, written only for the first of the four choirs under his control, was ‘incomparably harder and more intricate’ than the concerted music entrusted to the second choir.Footnote 52

Instances of large numbers of singers performing older polyphony or even chant have mistakenly been taken as confirmation that Bach would have wished to use comparably large vocal ensembles in his own music. But distinct repertories made distinct musical demands and commonly presupposed distinct vocal forces. The traditional motet repertory, as Johann Mattheson tells us, possessed ‘a wholly other character’ than concerted music,Footnote 53 and its relative simplicity invited relatively large vocal forces.Footnote 54

Concertists and Ripienists (EBC, 29–41) Even when a vocal ‘Capella’ or ripieno group was also present, it was the concertists who constituted ‘the principal choir’Footnote 55 and who as such retained prime responsibility for choruses, not just intervening in them from time to time (as both Schering and Ehmann seem to imply) but singing from start to finish.Footnote 56 From Martin Heinrich Fuhrmann, for example, we learn that: concertists sing throughout all choruses, ripienists do not (often) do so and ripieno parts are (usually) optional.Footnote 57 (The second point is examined in the main text. As to the third point, we have noted Bach's explicit treatment of bwv71's ripieno parts as optional, following a tradition that reaches back to Michael Praetorius; in at least two other cases, moreover, the ripieno set is believed to have been added some years after the work's first performance.Footnote 58) As with Fuhrmann, so with Bach. For concertists to sing throughout all choruses was incontestably standard practice in Bach's own works, as it was for all vocal concerted music of his time, whether or not ripienists were also participating.Footnote 59 (Universally acknowledged in Bach scholarship, this critical feature of the concertist's role is nevertheless almost the exact reverse of most current practice:Footnote 60 ‘soloists’ have been rendered redundant – and mute – in choruses by the encroachment of ever-present ‘choirs’, giving us the musical oxymoron of ‘tutti’ sections no longer performed by ‘all’.)

Nor are there grounds for imagining that Bach's ripieno group would necessarily have been any larger than the one-to-a-part concertists' choir that it supported. The Württemberg court's eight singers were sufficient for a ‘quatuor with its ripieno’ in 1714 (see p. 32 below),Footnote 61 and in three instances Bach himself uses the term ‘Ripieni’ all but explicitly to denote individual singers in a vocal quartet.Footnote 62 Not only did a ripieno group commonly mirror the formation of the concertists' choir (thus SATB in Bach's case), it also sang as a discrete unit ‘separately positioned in a place apart from the concertists’, as Fuhrmann puts it.Footnote 63 This principle runs right through concerted music-making from its inception; Ignatio Donati, for example, informs us in 1623 that the optional ripieno parts he provides can form a second choir ‘sù la cantoria’,Footnote 64 while Mattheson in 1713 simply allocates his ‘Capella’ singers and his concertists to separate ‘choirs’.Footnote 65 Similarly, any additional ripienists, rather than simply swelling the ranks of the existing body (as in today's choral practice), might equally well form a further discrete one in yet another location.Footnote 66 This additive process of expanding vocal forces is presumably what is represented in the oft-reproduced frontispiece to Unfehlbare Engel-Freude (1710), where, as Schering points out, three vocal quartets are plainly visible.Footnote 67

Copies and Copy Sharing (EBC, 43–57) Placing concertists and ripienists in discrete choirs inevitably dictates that each group be provided with its own set of parts. Surviving performance materials for Bach's choral works, however, include very few ripieno parts (see p. 28 below), leading Schering to surmise that ‘if need be, the tutti singers could also sing from the concertists' parts, in the event that time did not permit the copying out of the other [parts]’.Footnote 68 To remedy the lack of written indications in these circumstances, ‘a sign from the conductor sufficed to bring the ripienists back in at the desired place’.Footnote 69 Yet when this idea is traced back to Praetorius and ultimately to Ludovico da Viadana, we find that it merely relates to the routine cueing of ripienists equipped with their own copies and standing in separate choirs.Footnote 70 (As Rifkin puts it: ‘The situation resembles that of the present-day timpanist who has to count huge stretches of rest and surely appreciates a confirmatory nod from the conductor.’Footnote 71) If we are to imagine that Schering's conjectural stopgap was ever adopted outside truly exceptional circumstances, we must surely ask: would it really have taken Bach so long to add a dozen or so valuable solo/tutti indications to a set of concertists' parts? One minute? Five minutes?Footnote 72

The still widely accepted hypothesis of a ‘group of three’ singers reading from a single (concertist's) partFootnote 73 has long ceased to be regarded as the mere stopgap measure originally proposed by Schering. It now forms a cornerstone of the twelve-strong Bach choir and has even been quietly extended to accommodate ‘sixteen or more singers’ on those occasions when Bach did have time to prepare a set of ripieno parts.Footnote 74 Yet Schering's memorable image not only stands in contrast to the ‘groups of four’ in quartet formation that he himself identifies in the engraving from Unfehlbare Engel-Freude but appears to remain uncorroborated by any other relevant source. Attempts to introduce iconographic evidence of copy-sharing are once again undermined by the failure to differentiate between the conventions of distinct repertories; why else would an essay on Bach's forces for concerted music lead with an engraving of a Cantor and half a dozen or more men and boys singing around a lectern from a large book of monophonic chant?Footnote 75

Not only do the copies used by Bach's concertists bear no signs of having been shared, they show to a considerable degree that they actually were not.Footnote 76 Similarly, a careful study of the eight hundred or so Telemann cantatas at Frankfurt am Main concludes ‘that only one singer sang from each part, and that concertists and ripienists did not share parts’.Footnote 77 If this is so, then why are there so few ripieno copies amongst Bach's own performance material?Footnote 78 Of almost 150 extant sets of parts, just ten include parts for ripienists.Footnote 79 To believe it ‘likely that many ripieno parts were indeed produced … and subsequently lost or disposed of’ is merely to reiterate the unsubstantiated belief that Bach's own performances involved a ripieno choir on a regular basis.Footnote 80 Schering's explanation is that ‘less importance may have been attached to their preservation’ than to those for concertists, because, by contrast, they would not have contained all sung portions of a work.Footnote 81 Yet if these hypothetical ripieno parts really had been considered musically desirable for performance (let alone essential), it seems strange that so many would apparently have gone missing, at least at an early stage.Footnote 82

The ‘Entwurff’ (EBC, 93–102) If the careful examination of Bach's performance material has opened up the nature of his vocal forces for reconsideration, it is the composer's 1730 ‘Entwurff einer wohlbestallten Kirchen Music’ that remains the bedrock of traditional thinking on the subject. The document's concerns, however, are fundamentally logistical rather than artistic: how to maintain the forces necessary to provide music year round in four different churches, given an official total strength of just eight town musicians and thirty-two (of fifty-five) alumni (only seventeen of them ‘usable’ in either of his top two choirs). How the music is to be performed is never directly addressed, only how to keep the show on the road: ‘Each “musical” choir must have at least three sopranos, three altos, three tenors, and as many basses, so that even if one person falls ill … at least a two-choir motet can be sung.’Footnote 83

Describing the ‘Entwurff’ as the ‘most telling’ documentation of ‘the puny resources Bach had to work with, and those that he would have thought adequate if not ideal’, Richard Taruskin proceeds to quote a parenthetical passage which has long appeared to offer a uniquely authoritative and clear-cut statement on performance: with four singers for each voice, Bach appears to say, one ‘could perform every chorus with 16 persons’.Footnote 84 This critical mistranslation, long identified as such, comes straight out of the old Bach Reader of 1945. From The New Bach Reader of 1998, on the other hand, we learn that Bach is in fact merely addressing the organizational matter of how many singers should belong to each of the Thomasschule's three ‘musical’ choirs: with four singers of each voice type, one ‘could provide every choir with 16 persons’.Footnote 85 This may be disappointing, as it hardly answers our questions, but it should not really be surprising, since the section in which the passage appears has no demonstrable connection with the performance of concerted music in the first place.

Rosters and Additional Performers (EBC, 103–15) The ‘Entwurff’ has usually been taken at face value as indicating poor performance conditions,Footnote 86 and – as often as not – it is the ‘small numbers’ of musicians at Bach's disposal that are taken to exemplify these poor conditions. Thus:

By Bach's own avowal … he considered thirty-four persons (plus himself and another keyboard player, who went without saying) to be the bare minimum required for a performance of a maximal piece like Cantata No. 80 [‘in his son's “big band” arrangement’] – and that number would have been thought puny indeed at any aristocratic, let alone royal, court.Footnote 87

This recent reading by Taruskin will stand for many. Its purpose is to show that Bach ‘never had at his disposal the musical forces that could do anything approaching justice to this mighty fortress of a chorus’Footnote 88 – the opening movement of Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott bwv80 in the version with trumpets and drums. (Perhaps we are meant to understand that Bach's forces were so inadequate that he even had to make do without these posthumously added instruments.Footnote 89)

Several things are wrong here. In addition to inflating the instrumental tally (albeit mildly)Footnote 90 and assuming in familiar fashion that a full quota of twelve singers would necessarily all be ‘required’ to perform a chorus of this sort, Taruskin has mistakenly treated the list of instruments in the ‘Entwurff’ as a simple minimum.Footnote 91 Bach's overall figures – purely aspirational as they may have been – are certainly no ‘bare minimum’; rather, they represent his considered view of ‘a properly constituted church musical establishment’, one which naturally enough could encompass even a ‘maximal’ scoring with three oboes, trumpets and drums.Footnote 92 Achieving these numbers, at least with adequate quality, manifestly posed a major challenge to Bach – though hardly with the alarming results Taruskin alleges: ‘as Bach complains, most of the time some parts had to be omitted from the texture altogether due to absences’.Footnote 93 If anything had to go, it would naturally be the optional vocal ripieno group, leaving the compositional texture intact.

So, just how ‘puny’ would a musical establishment of twelve singers and twenty or so instrumentalists have seemed to a contemporary court? Curiously, the comparison Taruskin offers (see Figure 2) is with Handel's Fireworks music, an occasional piece written for outdoor performance by a quite exceptional fifty-five-piece wind band made up of both court and freelance players.Footnote 94 Even northern Europe's most glittering court, in Dresden, would have been hard put to muster anything remotely comparable.Footnote 95

Figure 2

Whether or not the numbers outlined by Bach ‘would be considered stingy for a professional performance today’,Footnote 96 they correspond reasonably closely to those of musical establishments at several major German courts in Bach's own time. The Württemberg court in 1714, for example, maintained a thirty-five-strong Kapelle, and a document from Würzburg (1740) outlines a ‘most compendious court Kapelle or church musical establishment’ of 36 persons, comprising twelve singers, twelve strings, six woodwinds, four brass, organ and theorbo.Footnote 97

On a more modest scale, Mattheson nevertheless reflects the steady expansion of instrumental resources both at courts and in towns during the first half of the century. Rejecting Beer's earlier model of a seven-person nucleus for a Kapelle, he proposes instead a body of at least twenty-threeFootnote 98 – which ‘in republics can be more easily increased than at courts, if one wishes to do anything about it’.Footnote 99

However common they may have been in Bach's lifetime, ensembles of these dimensions have come to be viewed with a pitying eye: ‘circumstances in many other cities were hardly better [than at Leipzig] and in many cases worse: had Bach gone to the Jacobikirche, Hamburg in 1720, he may have had no more than half a dozen adult singers and fifteen or so instrumentalists, plus trumpeters on occasion’.Footnote 100 The example usefully highlights another aspect of these comparisons: that in these various musical establishments singers were routinely outnumbered by instrumentalists – and usually by a significant margin. Given that the full rosters may be considered unduly ‘small’ today (especially for the performance of ‘great’ music), it is no surprise to find their vocal contingents so often dismissed as positively ‘inadequate’. Yet a figure of eight singers ‘seems to have represented something of a traditional norm’.Footnote 101 At one end of the spectrum Mattheson's four were still evidently considered sufficient for concerted music,Footnote 102 and at the other the suggested sixteen for Leipzig would have eclipsed even Würzburg. Whereas by statute each of Bach's choirs comprised just eight singers,Footnote 103 his stables of ‘at least’ twelve were explicitly designed, as we have seen, to provide insurance against absences (‘so that even if one person falls ill …’). With only eight the WürttembergKapelle remained vulnerable:

Vocalisten haben wir so wenig, das wür just, ein quatuor mit seiner Ripien in der Hofcappella khönnen besetzen, solte aber ein oder der ander Krankh werden, so khan dises auch nicht geschehen, das mann als nur mit 2: oder 3: etwas machen khan, welches ja für eine so vornembe Hochfürstl: Cappella nicht anständig ist.Footnote 104

We have so few vocalists that we can just manage a quatuor with its ripieno in the Hofkapelle, and should any of them fall ill, even this is not then possible, so that one can do something, say, with only two or three, which is certainly not becoming for such a noble Princely Kapelle.

It is clear that none of these figures measures up to today's expectations of a ‘proper’ choir, causing many commentators to invoke various categories of additional singer – sometimes whole ranks of choirboys (at Weimar,Footnote 105 DresdenFootnote 106 and Hamburg, for example), and at Leipzig individual externi (dayboys) and university students.Footnote 107 As a counterbalance, we may note the widespread use of ‘choirboys’ as instrumentalists rather than as singers – at the Württemberg court, where in 1717 its two Kapellknaben both played viola in concerted music,Footnote 108 at Dresden, where the young Franz Benda did the same in the early 1720s,Footnote 109 and – not least – in Bach's Leipzig.Footnote 110 Indeed, it seems that at Hamburg later in the century the majority of boys played no role whatsoever in concerted music-making, as we learn from the responses to one of a series of questions put to C. P. E. Bach's daughter at his death in 1788 concerning the nature of his church duties:

Ob er die Chor Knaben mit zu Chören usw. gebraucht habe, und wie viel er solche bezahlt?

Nein, von dem was er von der Kammer und den Kirchen erhält, wird ein Knabe[,] der eigentlich in den Rechnungen Chorknabe genennet wird, gehalten. Dieser muß die kleinen Geschäfte besorgen, z. B. die Noten in die Kirche und zu Hause tragen, den Feuerschapen ins Musik Chor bringen u. dgl. Die übrigen Chorknaben gehen den Director nichts an.Footnote 111

Did he include the [fourteen] choirboys in choruses etc., and how much did he pay them?

No; one boy, named as choirboy in the accounts, is supported by what he receives from the board and the churches. He has to take care of the small jobs such as carrying the music to the church and back home, bringing the warming-pan to the choir loft and so on. The remaining choirboys are no concern of the director's.

Rosters (and payment lists) rarely tell the whole story. Certain categories of additional performers may well remain undocumented,Footnote 112 but, equally, even a complete documented body of performers had to accommodate both absences (particularly, in the case of singers, through illness) and the diverse musical requirements of different repertories (from chant to elaborate concerted music). Whilst Bach's ‘Entwurff’ catalogues various ‘troublesome aspects of the organizational structure’ of one such body (of a size perfectly in keeping with Leipzig's status), it ‘simply does not allow for a reconstruction of the composition of the actual vocal-instrumental ensemble’ used in Bach's own performances – not because ‘essential groups of musicians’ (real or imagined) are omitted,Footnote 113 but because this administrative memorandum did not need to explain what even unmusical town councillors would already have observed from week to week: that, in contrast to chorales and motets, the defining characteristic of concerted church music of the time was that it offered a platform not only to an instrumental ensemble but to ‘the selected best singers’ – a choir of (four or so) concertists.Footnote 114

Instrument/Singer Ratios (EBC, 117–129) If the ‘Entwurff’ gives us a reasonable idea of Bach's aspirations for an instrumental ensemble at Leipzig but is reticent on what role(s) his vocal resources might play in concerted music, we may enquire whether the instrumental proportions themselves suggest anything about singer numbers. Conventional wisdom is that larger instrumental forces dictate larger vocal forces.Footnote 115 Generally neglected in this context are those sources – both documentary and iconographic – that detail actual performing ensembles, as opposed to musical ‘establishments’. Seven clear-cut examples from Germany (from the 1720s to about 1750) show instrumentalists and singers in ratios of 2.5:1 up to 6:1,Footnote 116 including the ensemble sent from Dresden to perform in the chapel at the Hubertusburg palace under Zelenka's direction in 1739, which consisted of fourteen instrumentalists and five singers (a ratio of almost 3:1).Footnote 117 Comparisons using estimates for five selected Leipzig works by Bach point clearly in the same direction: numbers of instruments drawn from the ‘Entwurff’, when set alongside numbers of singers assuming four concertists with or without four ripienists, produce ratios of the same order: from almost 2:1 up to 6:1.Footnote 118 Revealingly, similar calculations based on twelve-strong and sixteen-strong choirs diverge quite sharply from the evidence of these sources. However numerous the instruments, a small group of concertists singing one to a part (with or without the occasional addition of a similar group of ripienists) seems to have been what concerted vocal music in Bach's time was all about.