The Mediterranean diet (MD) gained much recognition and worldwide interest in the 1990s as a model for healthful eating habits. This ‘popularity’ has continued to increase, among both the general public and the scientific community(Reference Alexandratos1–Reference Lairon3).

The principles underlying the MD form the basis of different sets of dietary guidelines from around the world, where the emphasis is on increasing intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts, grains, pulses, fish and low-fat dairy products, and opting for monounsaturated fats such as olive oil(4–6). The MD is highly advocated for its health-promoting and disease-preventing characteristics; yet, ironically, during recent decades there has been a gradual abandoning of the MD diet by the populations of the Mediterranean, especially among the younger generations(Reference Alexandratos1, Reference Belahsen and Rguibi7–Reference Greco, Musmarra, Franzese and Auricchio14). Simultaneously, while epidemiological research on the protective role of the MD is highly publicised, little is known about the use and effectiveness of MD education interventions. The purpose of the present paper was to carry out a preliminary exploratory study of published articles on the MD as a nutrition education tool. This was not a full-scale systematic review, but more of an introduction to the phenomenon.

Methodology

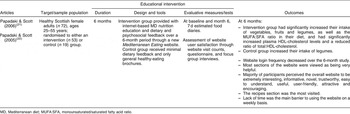

Two online searches were conducted within PubMed citation database using the terms ‘Mediterranean diet’ and ‘Education’ or ‘Intervention’. The 258 abstracts yielded were screened for distinct studies with a clear ‘education’ component, education being defined as some form of instruction to participants on the application of MD principles in their diet. Four studies met this criterion and these were further analysed for sample/target population, and educational intervention design, duration, tools, evaluative measures/tests and outcomes. Full details of this analysis can be seen in Tables 1–4. A brief summary of each study is given below.

Table 1 A Mediterranean diet educational intervention with healthy Canadian females

MD, Mediterranean diet.

Table 2 Comparison of two educational interventions promoting Mediterranean diet nutrition behaviour among an at-risk Dutch population

SES, socio-economic status; MD, Mediterranean diet.

Table 3 The Mediterranean Eating internet-based educational intervention with healthy Scottish females

MD, Mediterranean diet; MUFA:SFA, monounsaturated/saturated fatty acid ratio.

Table 4 The Mediterranean Lifestyle Program with American postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes

MLP, Mediterranean Lifestyle Program; UC, Usual Care; MANCOVA, multivariate analysis of covariance.

Results

Study 1

A group of Canadian healthy female adults participated in a 12-week programme promoting the Mediterranean food pattern(Reference Goulet, Lamarche and Lemieux15–Reference Lapointe, Goulet, Couillard, Lamarche and Lemieux18). The programme comprised two group sessions and seven individual sessions with a dietitian (three counselling sessions plus four 24 h recalls). During the first group session, a dietitian explained the major principles and health benefits of following a MD. Four weeks after the beginning of the intervention, subjects participated in a Mediterranean cooking lesson during which they had to produce a complete meal. Individual sessions took place during weeks 1, 6 and 12 to evaluate dietary changes and to select further objectives to increase adherence to the MD. During individual sessions, the dietitian used the FFQ and the Mediterranean food pyramid to promote dietary changes compatible with the participant’s food preferences. Unannounced qualitative 24 h recalls were performed by a dietitian over the telephone at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 10. The objective was to reinforce the key principles of the MD and provide participants with additional support.

Evaluation using FFQ took place at intervals during the programme and 12 weeks after the end of the programme (week 24). Adherence to the programme, also as evidenced by a MD score, led to a small but significant decrease in weight and waist circumference, a reduction in dietary energy density, and was associated with a decrease in circulating oxidised LDL. Adopting a MD pattern of food intake was not associated with increased daily dietary or energy economic cost. Women without children or who used available food discounts to plan their food shopping showed a better dietary response to the MD advice given.

Study 2

A study with Dutch adults from a socio-economically deprived area, and who had hypercholesterolaemia and at least another two risk factors for CVD, compared the use of two types of MD education interventions (intervention group 1 – group education; intervention group 2 – group education plus individual tailored letter) with a ‘care as usual’ (control) group(Reference Siero, Broer, Bemelmans and Meyboom-de Jong19, Reference Bemelmans, Broer, de Vries, Hulshof, May and Meyboom-De Jong20). Both intervention groups participated in three 2 h interactive group sessions, in which they were briefed on CVD risk factors and on the basic components of the healthy MD; a positive attitude to the MD was encouraged and they were given practical tips on how to adopt a MD food pattern. Booklets with core information from the course were also distributed (or mailed to non-attendees) at the end of each session. A container of diet margarine was also distributed. Members of intervention group 2 also received a Prochaska-based individualised letter in-between group session two and three. The letter contained additional MD-related information and was tailored to their attitude, self-efficacy, social norm and stage of change. The control group just received a leaflet with the Dutch Nutritional Guidelines and usual care by a general practitioner. The educational aspect of the intervention lasted for 16 weeks.

FFQ that emphasised Mediterranean type foods were administered at baseline and weeks 16 and 52. Biochemical and clinical assessments were conducted at weeks 0 and 52, measuring, amongst others, serum cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as weight and height. The various results obtained showed that substantial dietary behaviour change can be achieved even by a brief interactive group education intervention on the positive health effects of the MD. Such group education competes in efficacy with individual tailored letters. In fact, there were a number of beneficial changes in dietary habits in the intervention groups compared with the control group, including increased fish, fruit, vegetable and (in the long-term) bread and poultry consumption, and decreases in total fat and saturated fat intake. However, at week 52 the intervention group had not lowered their serum cholesterol levels significantly more than the control group. Moreover, BMI had increased for both intervention and control groups, and total fat and saturated fat intake were still too high.

Study 3

A study with Scottish healthy females aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a 6-month internet-based, stepwise, tailored-feedback intervention promoting key components of the MD(Reference Papadaki and Scott21, Reference Papadaki and Scott22). A Mediterranean Eating website was developed based on various theories including the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Aesthetically the website was given a ‘Mediterranean feel’ and provided healthy eating, shopping and cooking tips, adjusted to reflect and promote the MD. A new set of approximately twenty Mediterranean recipes was added every fortnight. The recipes were inspired primarily by Greek and other Mediterranean dishes. However, recipes for popular Scottish dishes prepared in a Mediterranean style (e.g. with a greater variety and amount of vegetables) were also included. An intervention and a control group were set up. Participants in the intervention group were given information on secure access to the website, and they were emailed weekly and encouraged to visit the website and the updated sections. Eventually, they also received dietary and psychosocial feedback on their food intake. Control group participants received very little feedback and only healthy-eating brochures.

A process evaluation of the website which took place as the intervention progressed indicated that, overall, the majority of the intervention participants perceived the website to be extremely interesting, informative, useful, trustworthy, easy to understand, novel, attractive, encouraging and user-friendly. The recipes section was the most visited. Visits to the website decreased over the duration of the intervention, with lack of time being reported by participants as a prime barrier to using the website on a weekly basis.

Comparative analysis of 7 d estimated food intake diaries at baseline and at 6 months revealed that the intervention group had significantly increased their intake of vegetables, fruits and legumes, as well as the MUFA:SFA (monounsaturated/saturated fatty acid) ratio in their diet. They also had significantly increased plasma HDL-cholesterol levels and reduced the ratio of total:HDL-cholesterol. The control group also increased their intake of legumes, but saw no other significant beneficial changes compared to baseline. The authors concluded that such an online intervention holds promise in encouraging a greater consumption of plant foods, together with increasing monounsaturated fat and decreasing saturated fat in this type of population.

Study 4

This study tested the effectiveness of a comprehensive self-management Mediterranean Lifestyle Program (MLP) in reducing cardiovascular risk factors in American postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes(Reference Toobert, Glasgow, Strycker, Barrera, Radcliffe, Wander and Bagdade23, Reference Toobert, Strycker, Glasgow, Barrera and Bagdade24). Subjects were randomised to a treatment (MLP) or control (usual care (UC)) group. All intervention materials and venues were given a ‘Mediterranean feel’ and the programme comprised education and training in preparing a Mediterranean-type low-saturated fat diet, stress management, physical activity, smoking cessation (where necessary) and group support skills. The intervention lasted for 6 months: it started with a 3 d non-residential retreat, followed by weekly 4 h meetings which consisted of 1 h each of physical activity, stress management, group Mediterranean potluck dinner and support groups. In the programme, a dietitian individualised carbohydrate and fat intake for each participant in order to optimise blood glucose and lipid concentrations, while still being faithful to the dietary patterns of the MLP.

At month 6 – the end of the intervention – compared to baseline, the MLP treatment group had significantly greater improvements compared with the UC control group on serum lipids, HbA1c, BMI, weight and quality of life. They also fared significantly better with respect to physical activity, stress management/coping, smoking cessation and psychosocial variables (self-efficacy, social support and problem-solving ability). The authors proposed that, through the MLP, such a target group can make comprehensive lifestyle changes that may lead to clinically significant improvements in glycaemic control, some CHD risk factors and quality of life.

Discussion

This brief introductory overview of interventions which had a clear MD education component indicates that such education can have a positive impact on food intake and, consequently, strong potential for reducing health risk factors. The interventions targeted both healthy and at-risk populations and lasted between 12 weeks to 1 year, including follow-up. The MD education component used individual counselling, tailored computer-based counselling, group education, internet-based education, cookery demonstrations and classes, and take-home printed materials. Outcomes studied included adherence to the MD diet and its impact or relation to body weight, waist-to-hip ratio and lipid profiles. Outcomes were measured using food diaries and FFQ, often using MD scores to assess adherence to the diet, questionnaires on psychosocial factors and on usage of the educational tools, as well as anthropometrics and biomarkers. Interventions showed statistically significant increases in intake of vegetables, legumes, nuts, fruit, whole grains, seeds, olive oil and dietary PUFA and MUFA, and statistically significant decreases in total cholesterol, ox-LDL-cholesterol, total:HDL-cholesterol ratio, insulin resistance, BMI, body weight and waist circumference.

In two of the studies, it was also proposed that using MD nutrition education may be a relatively cost-effective strategy for improving health and reducing health-risk factors. Similarly, in a recent study in Australia, which evaluated the economic performance of ten nutrition interventions, MD intervention emerged among the most cost-effective, where economic performance was expressed as cost per QALY (quality adjusted life year) gained(Reference Dalziel and Segal25). The authors concluded that such nutrition interventions can constitute a highly efficient component of a strategy to reduce the growing disease burden linked to over- or under-nutrition.

This brief overview also reinforces the proposition made earlier that there seems to be a gap in the literature with respect to implementation and evaluation of MD education interventions. The four studies reported all took place outside the Mediterranean region. Little seems to be known internationally on how Mediterranean nations themselves are promoting the MD in their public health campaigns. It is likely that many interventions are carried out, but are not reported beyond the countries’ borders. For example, in the early 2000s, the then Maltese Health Promotion Department published a leaflet on the value of the MD which it often used as a basis for presentations in different community settings and which was disseminated widely through health fairs, in schools and from its outreach offices. The Department also launched a Cancer Prevention recipe book that included recipes following the MD approach(26). In addition, traditional Maltese healthy foods are regularly promoted during Home Economics lessons in Maltese schools. Interestingly, a study with Cretan primary school children concluded that attempts to introduce the principles of the MD to children through nutrition education requires innovative, enthusiastic and highly motivated teachers(Reference Kafatos, Peponaras, Linardakis and Kafatos27).

Undoubtedly, one can adopt various channels and media for using the MD as a nutrition education and health promotion tool. The four studies reported earlier used a variety of media and, even when there was little face-to-face interaction, personalisation made a difference. Essentially, messages are more effective if they are based on theory, targeted, made easily accessible and their applicability is clear for the intended audience. Even food labelling may be a vehicle for promoting the MD. Recently, the US-based Oldways group launched the Mediterranean Mark for food packaging as a ‘gold standard for healthy eating’ and to help consumers identify ‘Med Diet food’(28). Such labelling could serve as a valuable point-of-purchase educational tool complementary to other MD education strategies.

Conclusion

MD education interventions may help protect against and treat a variety of health problems in different populations. More extensive research is required to review interventions which have used MD education and strategies which were effective in bringing about positive health behaviour change. Mediterranean countries themselves need to publicise the outcomes of their campaigns in international fora and scientific publications. In the meantime, the results of this introductory review could help inform the choice and design of future MD nutrition education for specific target populations.