Article contents

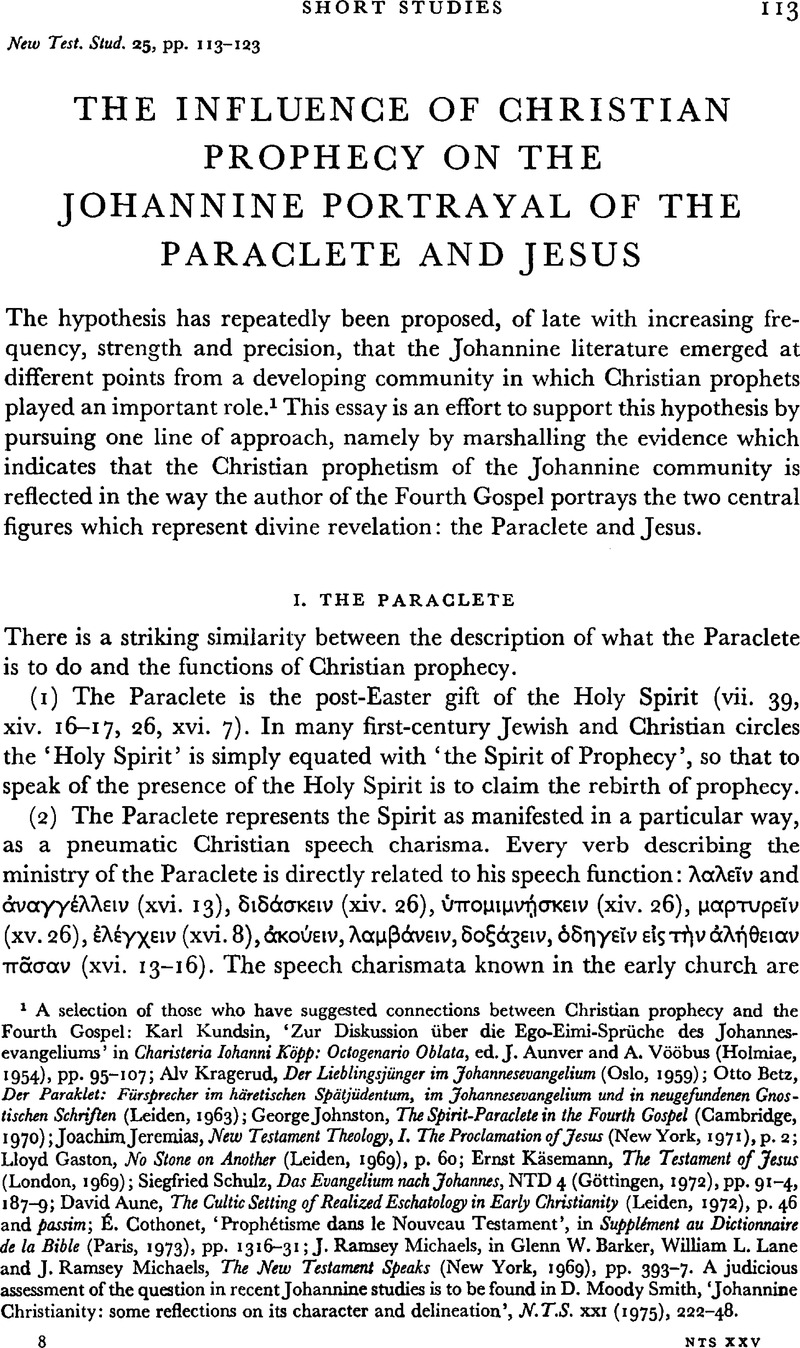

The Influence of Christian Prophecy on the Johannine Portrayal of the Paraclete and Jesus

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1978

References

1 A selection of those who have suggested connections between Christian prophecy and the Fourth Gospel: Karl Kundsin, Zur Diskussion ber die Ego-Eimi-Sprcne des Johannesevangeliums in Charisteria lohanni Kpp: Octogenario Oblata, ed. Aunver, J. and Vobus, A. (Holmiae, 1954), pp. 95107Google Scholar; Alv Kragerud, , Der Lieblingsjnger im Johannesevangelium (Oslo, 1959)Google Scholar; Betz, Otto, Der Paraklet: Frsprecher im hretischen Sptjdentum, im Johannesevangelium und in neugefundenen Gnostischen Schriflen (Leiden, 1963)Google Scholar; Johnston, George, The Spirit-Paraclete in the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge, 1970)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Jeremias, Joachim, New Testament Theology, I. The Proclamation of Jesus (New York, 1971), p. 2Google Scholar; Gaston, Lloyd, No Stone on Another (Leiden, 1969), p. 60Google Scholar;Ernst Kasemann, The Testament of Jesus(London, 1969); Siegfried Schulz, Das Evangelium nach Johannes,NTD 4 (Gottingen, 1972), pp. 914, 1879; David Aune, The Cultic Setting of Realized Eschatology in Early Christianity (Leiden, 1972), p. 46 and passim; . Cothonet, Proph6tisme dans le Nouveau Testament, in Suppliment au Dictionnaire de la Bible(Paris, 1973), pp. 131631; Michaels, J.Ramsey, in Barker, Glenn W., Lane, William L. and Michaels, J. Ramsey, The New Testament Speaks(New York, 1969), pp. 393-7.Google Scholar A judicious assessment of the question in recent Johannine studies is to be found in D. Moody Smith, Johannine Christianity: some reflections on its character and delineation, N.T.S.xxi (1975), 22248.

1 M+gen. pl. means as one among a group in iii. 22, vi. 3, vii. 33, xi. 54, xii. 8, xiii. 33, xiv. 9, 30, xvi. 4, xvii. 12, xviii. a, 5, 18, xx. 7, 24, 26, mostly of the historical Jesus among his disciples, and never means within individuals. +dat. pl. always elsewhere in John means present with, but never in. E does sometimes in John mean within the individual e.g. v. 38, viii. 37, xv. 7 (God's or Jesus' word); v. 42, xvii. 26 (the love of God); vi. 53 (life); xvii. 13 (joy); and in the group of passages in which Jesus dwells in the believer (vi. 56, xiv. 20, xv. 4, xvii. 23, 26) though this latter usage may also fade into the meaning of among them, as in xvii. 20. But the ; is never said to dwell in the individual believer in the Fourth Gospel, and +dat. pl. often means among, e.g. ix. 16, x. 19, xi. 54, xv. 24 and xvii. 10. E ῑ in xii. 35 must be understood as among you, not within you, and is an exact parallel to the phrase in xiv. 17. The analogous phrase ῑ in i. 14 must mean among us. The data, together with the argument printed above, provide sufficient reason to translate ῑ in xiv. 17 with among you, in your midst, bei euch, chez vous, and to reject the ambiguous in you (RSV etc.) and especially in your hearts (J. B. Phillips). This corresponds exactly to the usage of ῑ in I Cor. xiv. 25, in a discussion of Christian prophecy.

2 One of the most incisive points in Johnston's Spirit-Paraclete is his view that refers to a definite group of leaders within the church, not to an attribute of every member of the church, pp. 84, 119, 1289. For the contrary view see Raymond, Brown, The Kerygma of the Gospel according to John, Interpretation xxi (1967), 3912Google Scholar, and his subsequent publications.

1 See Betz, Der Paraklet, Johnston, , The Spirit-Paraclete, and Sigmund Mowinckel, Die Vorstel-lungen des Sptjudentums vom heiligen Geist als Frsprecher und der johanneische Paraklet, Z.N.W. xxxii (1933), 97130Google Scholar. Eduard, Schweizer, ![]() , T.D.N.T. vi, 443Google Scholar, points out that the Johannine equivalent of the , the Spirit of Truth, is a phrase found in the New Testament world elsewhere only in Test. Jud. xx. 5, IQS iii. 18b, and Herm. Man. iii. 4, and that in each case it is thought of as an independent angelic figure.

, T.D.N.T. vi, 443Google Scholar, points out that the Johannine equivalent of the , the Spirit of Truth, is a phrase found in the New Testament world elsewhere only in Test. Jud. xx. 5, IQS iii. 18b, and Herm. Man. iii. 4, and that in each case it is thought of as an independent angelic figure.

1 See Betz, Der Paraklet, pp. 435Google Scholar, for a survey to 1963, and Raymond, Brown, The Gospel according to John (New York, 1970)Google Scholar, Appendix v, The Paraclete, pp. 113544Google Scholar, and now Ulrich, Mller, Die Parakletenvorstellung im Johannesevanglium, Z.Th.K. lxxi (1974), 3178.Google Scholar

2 See Conzelmann, Hans, Was von Anfang war, in Neutestamentliche Studien fr Rudolf Bultmann, ed. Eltester, Walther (Berlin, 1957), pp. 194207Google Scholar, and Klein, Gnther, Das wahre Licht scheint schon, Beobachtungen zur Zeit- und Geschichtserfahrung einer urchristlichen Schule, Z.Th.K. lxviii (1971), 261326.Google Scholar

3 See Schulz, Siegfried, Die Stunde der Botschaft: Einfhrung in die Theologie der vier Evangelisten (Zrich, 2 1970), pp. 3334, 344.Google Scholar

1 Thus Hoskyns, E. C.' protest (in The Fourth Gospel London, 1940, p. 468Google Scholar) that there is no foundation for the suppositionthat the Paraclete is a Christ-spirit prophetically leading and guiding the Christian fellowship, and freely authoritative apart from the event of the life and death of Jesus is well taken but wide of the mark, for all the Johannine writings would certainly agree, including the Apocalypse, which was certainly written by a Christian prophet. Hoskyns is certainly not justified in using this as a basis for rejecting the view that Christian prophecy is an important factor in the creation of the Gospel. Nor is it satisfactory to handle the matter as does Yves Congar, who minimizes the aspect of newness in the truth proclaimed by the Paraclete: Apostolic tradition is thus always both historical and pneumatic or charismatichistorical in its origin and in the materiality of its content; pneumatic or charismatic in the power that is at work in it, for John makes it clear that the Paraclete brings new content, and not only new power (xvi. 1213). See Congar, , Tradition and Traditions (New York, 1968), pp. 1619.Google Scholar

2 A ist in den johanneischen Schriften ganz einfach die christliche Offenbarung. In dem Ausdruck Geist der Wahrheit ist die Wahrheit die durch das Wirken des Geistes fortgesetzte Offenbarung alles dessen, was zu Christi Person und Werk gehrt. Johanssen, Nils, Parakletoi: Vorstellungen von Frsprechern fr die Menschen vor Gott in der alttestamentlichen Religion, im Sptjdentum und Urchristentum (Lund, 1940), p. 260.Google Scholar

1 The member of the Johannine school who wrote the Epistles is either more oriented to this development himself, or represents a later date when the danger of unbridled pneumatism in Gnosticism was more apparent so that he felt compelled to back away from it in the direction of Frhkatholizismus, or both.

1 This one instance of is helpful in that it reveals something of John's understanding of the prophetic function in a purely formal way. Caiaphas prophesies (unconsciously, of course) in that he does not speak ' ἑṽ, in that he interprets the meaning of the historical event of Jesus' life and death so as to reveal its salvific character, and in that he predicts the future.

2 Both Jesus and the Paraclete are sent by the Father (xiv. 16, 26, xv. 26v. 30, viii. 16, 42, xiii. 3, xvi. 27, xvii. 8), but the world will not receive either (xiv. 17i. 10, 12, viii. 14, 19, xvii. 8). Both thereby convict the world of sin (xvi. 8iii. 20, vii. 7). Neither Jesus nor the Paraclete speaks ἀ' ἑṽ, but both speak what they are given to speak (xvi. 13vii. 1617, xii. 49, xiv. 24). Both interpret the Jesus-event as the Heilsgeschehen (xvi. 814iii. 15, ἑ sayings). Both predict the future (xvi. 13x. 16, xiii. 19, xiv. 29, xvi. 2). The Paraclete bears witness to Jesus (xv. 26), and, despite disclaimers (v. 31), Jesus bears witness to Jesus (viii. 14, 18). For a more complete discussion, see Bornkamm, Gnther, Der Paraklet im Johannesevangelium, in Neutestamentliche Studien fr Rudolf Bultmann, ed. Eltester, Walther (Berlin, 1957).Google Scholar

1 Rev. ii. 23, iii. 8, 15, v. 6; such visions as vi. 1217 would put the hearer in the presence of the last judgment, and reveal his own heart. For Paul, compare I Cor. iv. 5, which relates revelation of the heart's hidden secrets to the last judgment, though with his characteristic eschatological reservation, and I Cor. xiv. 245, where the prophetic phenomenon causes this to happen already in the worship of the church.

1 As in Mark iii. 20, also a context reflecting early Christian prophecy. See my article How may we identify oracles of Christian prophets in the Synoptic tradition?, J.B.L. xci (1972), 50121.Google Scholar

2 In the synoptic gospels, Jesus is the subject of άӡ only in Mark xv. 39Matt. xxvii. 50, of Jesus' cry from the cross, but άӡ is used five times of the cries of ṽ-possessed persons: Mark iii. II, v. 5, 7 (= Matt. viii. 29), ix. 26, Luke ix. 39. The Fourth Gospel reserves άӡ exclusively for Jesus' preaching (and John's), using άӡ in places where the synoptics had used άӡ, e.g. of the crowds in the triumphal entry and at the trial before Pilate. That άӡ can have prophetic connotations, e.g. refer to exalted, supernatural speech, is seen from its repeated use in the Apocalypse. Walter, Grundmann, άӡ, T.D.N.T. III, 898903 elaborates on the prophetic overtones of the word in paganismGoogle Scholar, the Old Testament, and Judaism, but seems to miss this connotation of John's usage.

3 Cf. Louis Martyn, J., History and Theology in the Fourth Gospel (New York, 1968), pp. 5768, 1514.Google Scholar

4 See my Oracles of Christian Prophets, pp. 51820.Google Scholar

5 Walther, Eltester, in Der Logos und sein Prophet, in Apophoreta: Festschrift fr Ernst Haenchen (Berlin, 1964)Google Scholar, argues that the Johannine prologue is best seen in Old Testament terms, and that the revealer is thought of as a prophet. This argument can be accepted only in the most general terms, for i. 118 moves on another plane than the one we have been discussing above. Eltester goes too far we cannot dispense with mythology in understanding the Johannine but the model of Jesus as a prophet may still have hovered in the background of the evangelist's use of the myth. (See Jeremias', understanding of i. 9 in Der Prolog des Johannesevangeliums Stuttgart, 1967, p. 20Google Scholar, which he interprets to mean reveal in the prophetic sense, not illumine in the Hellenistic sense.) Even if the ό of Johni. 118 has nothing to do with the Old Testament הוהירבר, it is related to the late Jewish Wisdom speculation. And Wisdom came upon some and made them ṽ ṽ ὶ ![]() , Wis. vii. 14, 25 f.; Sir. i. 15. Note the use of in John xv. 15: ὑᾱ ὲ ἵ ὅ ἃ ἤ ἀ ṽ ό ἐ ὑῑ.

, Wis. vii. 14, 25 f.; Sir. i. 15. Note the use of in John xv. 15: ὑᾱ ὲ ἵ ὅ ἃ ἤ ἀ ṽ ό ἐ ὑῑ.

1 Jeremias, , Die Gleichnisreden Jesu (Gttingen, 8 1970)Google Scholar translated by Hooke, S. H., The Parables o, Jesus (London, 3 1972), p. 12Google Scholar. White's article in rebuttal, The Parable of the Sower appeared in J. T. S. xv (1964), 3007Google Scholar. And Jeremias replied with Palstinakundliches zum Gleichnis vom Semann (Mark. iv. 38 par.) in N.T.S. xiii (1966 1967), 4853.Google Scholar

2 Dalman, G., Arbeit und Sitte in Palstina, ii (Gtersloh, 1932), 206Google Scholar; hereafter abbreviated AS.

3 AS, ii, 207; cf. ii, 20515. Dalman, however, seems to contradict himself on II, 202, where he says that no ploughing is mentioned for the spring sowing in the ancient world because the soil is too moist. Linnemann, E., Gleichnisse Jesu (Gttingen, 3 1964)Google Scholar translated by Sturdy, J., Parables of Jesus (London, 1966), p. 180Google Scholar, also finds Dalman's reports sometimes contradictory.

- 1

- Cited by