In 1956, Dizzy Gillespie became the first jazz musician to participate in the State Department's Cultural Presentations program, a multifarious initiative to positively influence public attitudes towards the United States around the world while simultaneously fighting communist propaganda.Footnote 1 During two tours that year, Gillespie's large jazz ensemble performed more than one hundred concerts in eleven countries in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and South America.Footnote 2 A few months after the band returned from its second tour (to South America), Gillespie's recording label, Norgran, released Dizzy Gillespie: World Statesman, the first of two LPs purporting to document the band's ambassadorial trips. Along with a title that intimates political leadership, the liner notes, written by acclaimed jazz researcher Marshall Stearns, recount anecdotes from local newspapers and present the music as the “first half” of a tour concert. Dizzy in Greece, the second LP, took a similar approach. The disc placed Gillespie in a location of specific political relevance and portrayed the music as a concert for the State Department.Footnote 3

The LPs were well received by the jazz press. World Statesman appeared as a national bestseller in Down Beat four times between March and June 1957.Footnote 4 Despite criticizing the occasional lack of precision, reviewer Nat Hentoff characterized the band's music as “a collective storm” and Gillespie's playing in particular as “masterly.”Footnote 5 Dizzy in Greece, issued at the end of 1957, received four out of five stars from Down Beat’s Don Gold. Gillespie's playing on the record, according to Gold, is “the epitome of creative jazz” that “glows with warmth and excitement.” Gold goes on to extol the “incomparable drive” of the band and the “fascinating” arrangements as “the best efforts of some of jazz’ best writers.” Although he recommends this album as one “worth owning and hearing often,” he does remark that there is “no evidence that an audience is present for this concert performance, in Greece or anywhere else.” He further observes that the title “seems to be justification for use of the cover photo, of Gillespie in Greek garb.”Footnote 6

Gold was right to question the name, discographical details, and motivations of this record. The material on both records resulted from two recording sessions in New York City in June 1956 and April 1957. Moreover, several surviving programs from the Middle East tour reveal that despite their claim to represent performances abroad, the LPs contain only a small cross section of the repertory Gillespie and his band played during the State Department tours. The records also omit Gillespie's humorous interactions with band members and the audience that were a regular part of the band's onstage performance, as concurrent live recordings evince.

Using the discrepancies between the commercial recordings and tour performances as a starting point, this study interrogates how the business of selling jazz records intersected with nationwide debates about cultural diplomacy, international affairs, and racial politics in the United States at mid-century. Unlike the tour concerts, which served a specific political purpose for international audiences, the LPs were specifically designed so that domestic consumers might imagine jazz standing for the political ideals of the United States. I argue that these records were never meant to document the tours with veracity. Rather, the LPs were the product of a political and technological moment when Gillespie's record label could leverage musical diplomacy to sell records and thereby circulate an elevated vision for jazz within the country's cultural hierarchy.

Dizzy Gillespie as World Statesman

During the immediate post-WWII period, from 1945 to 1960, more than forty countries containing roughly a quarter of the world's population (approximately 800 million people) gained independence. In the fight for political dominance in these decolonized states, race relations and the Jim Crow institutional discrimination laws in the United States became a major point of emphasis for Soviet propaganda efforts.Footnote 7 As early as 1946, Soviet propagandists distributed reports about lynchings and poor labor conditions in the southern United States.Footnote 8 The State Department responded in several ways, one of which was to increase the visibility of African Americans abroad by sending distinguished authors, athletes, journalists, classical musicians, and other intellectuals on missions of cultural exchange. In the early 1950s, author J. Saunders Redding, journalist Carl T. Rowan, high jumper Gilbert Cruter, classical vocalist William Warfield, and the Harlem Globetrotters all toured on behalf of the U.S. government.Footnote 9 The State Department also began placing African Americans in their embassies across the world and allowed prominent figures such as attorney Edith Sampson to speak at public events.Footnote 10 Representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., one of the few black members of Congress, succinctly summarized this strategy when he told President Eisenhower in 1955 that “one dark face from the U.S. is as much value as millions of dollars in economic aid.”Footnote 11

That same year, Representative Powell helped persuade Eisenhower that jazz could be a useful addition in fighting Soviet propaganda abroad.Footnote 12 The American National Theater Academy (ANTA) oversaw the evaluation of participants for the Cultural Presentations program. With little knowledge about jazz, ANTA's music advisory panel sought the expertise of Marshall Stearns, who recommended Gillespie along with several other musicians.Footnote 13 Gillespie's dynamic ability and charismatic personality made him an ideal choice, although some policy makers in Washington still had concerns about sending jazz overseas. In a letter dated 30 January 1956, ANTA's general manager Robert C. Schnitzer asked Stearns to accompany Gillespie's band and advised him that “every precaution must be taken to assure that America's popular music is presented in such a way as to achieve the best results for our national prestige.” He continued, “We would also depend upon you to keep an eye on Dizzy's programs in order to see that he maintains the standards that have been set for them.”Footnote 14 From Gillespie's perspective, the trip presented an enormous musical opportunity because it allowed him to front a big band once again, something he had attempted several times previously with little financial success.Footnote 15

While on tour, Gillespie both praised the progress in U.S. race relations and spoke openly about Emmett Till, whose gruesome murder in 1955 made tangible the violent realities of African American life.Footnote 16 According to Jet magazine, local populations closely questioned Gillespie about Till's murder and about Autherine Lucy, the first black student to attend (and be unjustly expelled from) the University of Alabama.Footnote 17 In his autobiography, Gillespie also pridefully acknowledges the racially mixed and gender-inclusive demographics of his band, or what he called an “‘American assortment’ of blacks, whites, males, females, Jews, and Gentiles.”Footnote 18 Gillespie viewed jazz as a tool for goodwill that could “bring people together.”Footnote 19 In doing so, he also articulated a vision of the United States that was hybrid, mixed, and diverse, a position that many African American community leaders and public figures expressed at the time.Footnote 20 On stage, this way of thinking translated into skillful performances that entertained and educated through a combination of humor, wit, and musical displays of virtuosity.

The LPs in Context

Reports of Gillespie's activities abroad appeared in a wide array of print media. Jazz periodicals such as Down Beat and Metronome followed the tours closely, beginning with the official announcement from the State Department in November 1955. Coverage also appeared in the major newspapers of New York, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco, in addition to media that catered specifically to African Americans. These periodicals included newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, New York Amsterdam News, and Arkansas State Press, as well as magazines like Hue and Jet. Between April 1956 and July 1957, Esquire, Saturday Review, Variety, Newsweek, and Time—magazines that generally targeted an educated, middle-class audience—similarly published articles about this new, ambassadorial role for jazz.Footnote 21

This exposure led to numerous performance opportunities for Gillespie's ensemble. Between their return from the Middle East and the ensemble's second tour in South America in the summer of 1956, the band performed in New York City at Birdland and the Apollo Theater, at the White House for President Eisenhower, as well as at a civil rights rally in Detroit. Gillespie also made an appearance on Edward R. Murrow's Person to Person TV show.Footnote 22 From the Apollo to the White House and from television to print media, Gillespie's role as a cultural ambassador circulated through all layers of U.S. society, and his music was in high demand with audiences on both sides of the color line.

Within this mediascape, the owner of Gillespie's label, Norman Granz, issued two LPs featuring the State Department band, no doubt seeking to take advantage of this publicity.Footnote 23 The first, World Statesman, featured ten tracks of the band's material. Recorded in a single session on 6 June 1956 in a New York studio, World Statesman began to circulate later that year on Norgran, Gillespie's label at the time.Footnote 24 Granz issued the second ambassadorial LP, Dizzy in Greece, at the end of 1957 on his newly formed Verve label. Of the disc's ten tracks, seven were from the same June 1956 recording session that produced World Statesman; Gillespie's band recorded the other three in April 1957 (see Table 1).Footnote 25

Table 1. Track listing and recording dates for World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece.

Gillespie infused his big band with the musical qualities of bebop, emphasizing individual and often virtuosic improvisation. The band's compositions and arrangements feature complex melodies, intricate harmonies, and swift tempos mixed with typical gestures in the big band style: call-and-response figures between the brass and reed sections, melodies harmonized in four or five parts, full-band interludes between solos, and a chorus of through-composed material arranged for the entire ensemble in what is usually referred to as an “arranger's” or “shout” chorus. Tracks last between two-and-half to six minutes, with little variation in form. The typical arrangement includes an eight- to twelve-measure introduction, the melody orchestrated for a few soloists or the entire band, improvised solos (with band interludes), a shout chorus, and a restatement of the melody. As in bebop, the repertoire is a mixture of newly composed music and arrangements of standards from the so-called Great American Songbook. A hint of Gillespie's humor can also be heard in the band's novelty composition, “Hey Pete! Let's Eat More Meat.”

The LPs emphasize their connection to State Department tours at every level of design.Footnote 26 For example, one title portrays Gillespie as a diplomat, and the other places him in a location where he performed in his official capacity. The cover of World Statesman displays his silhouette with a plumed knight's helmet at his feet, a subtle allusion to a history of citizenship and military conflict in Europe and the United States. On the cover of Dizzy in Greece, Gillespie leans against a temple pillar dressed in a white fustanella, the Greek traditional men's costume. He also wears a pair of thick-rimmed sunglasses that subtly recall his hipster look from the 1940s.

The two unadorned back covers feature liner notes in the same organizational pattern. Written by Marshall Stearns, both liner notes recount the band's general activities in Eastern Europe and the Middle East through personal anecdotes and local newspapers reports and then briefly describe the musical content.Footnote 27 The notes to Dizzy in Greece focus on a specific event in Athens, which Stearns describes as the band's greatest diplomatic moment:

The band reached its peak, musically and diplomatically, in Athens where it out-rocked the rock-throwing Greek students. John “Dizzy” Gillespie and his ambassadors of jazz arrived just after the riots of May, 1956, and anti-American feeling was intense. Right or wrong, the Greeks felt that the United States should help them take Cyprus back from the British.Footnote 28 Newspapers were asking why the Americans were sending jazz bands instead of guns. And the opening concert was staged for the same students who threw rocks at the windows of the United States Information Service.

It was a tense moment and the students jeered as the band started to play. Then silence. And then, a complete and riotous switch—the roar of approval drowned out the big band; hats, jackets, and whatnot were tossed at the ceiling; and even the local gendarmes danced in the aisles. Between numbers, Gillespie miraculously kept the kids under control. After the concert, they carried him out on their shoulders, chanting “Dizzy, Dizzy, Dizzy,” stalling traffic for a half hour and a dozen blocks. This music spelled out the happy, friendly, and generous side of American life with explosive force and, incidentally, siphoned off a Niagara of excess energy.Footnote 29

By locating the band in Greece, both in title and tale, the LP calls attention to the music's potential to dispel violent tendencies and overcome perceived differences.Footnote 30 Peaceful excitement is key to Stearns's narrative. The stories of the students dancing in the aisles with the authorities and then carrying Gillespie into the street portray a moment of shared jubilation. Placed before the more typical descriptions of the musical content on the record, Stearns introduces the music through its ambassadorial function in order to show the positive outcome of music merged with diplomacy.

The carefully crafted packaging of both LPs told a particular story of jazz that garnered value both in the music's state-sanctioned status and its success with audiences abroad. Although not unprecedented, the explicitly political design was unusual for the time and a product of the technological moment in the jazz industry when record companies were selling more discs and making greater profits than ever before. According to the New York Times, from 1947 to 1957 industry-wide sales nearly doubled, from $203 to $360 million. At the same time, the long-playing record (LP), which Columbia Records introduced in 1948, was becoming a dominant format.Footnote 31 Between 1954 and 1956, unit sales of the LP rose from 11.1 to 33.5 million, resulting in a significant increase in percentage of industry sales, from 30% in 1953 to 61% in 1957.Footnote 32 The durable “vinylite” material of the LP could accommodate nearly three times the number of grooves per disc compared to the 78-rpm discs of the previous era. These “microgrooves” resulted in longer, uninterrupted playback time, which increased from four minutes per side for a 12-inch 78-rpm record to well over twenty.

During the transition to the LP, record labels increasingly devoted more resources to visual design and layout. More elaborate graphics and cover images, for example, began to replace the simple lettering and often recycled visual themes ubiquitous on records of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Record titles became progressively more poetic and evocative rather than simply descriptive.Footnote 33 The covers of World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece reflect the industry's changing priorities.Footnote 34 For example, the silhouette image of Gillespie that appears on World Statesman was a recycled photo from a 1954 LP titled Trumpet Battle featuring Gillespie and Roy Eldridge.Footnote 35 Norgran's use of existing visual material fit within the logic of the early 1950s record industry, when many labels reused visual content among their albums. In contrast to the predominantly unadorned white and blue background of World Statesman, Dizzy in Greece features an edge-to-edge image of Gillespie and his trumpet. The vibrant color of his Greek outfit stands out against the monochromatic yet memorable background of the textured stone columns.Footnote 36

Liner notes developed alongside the industry's adoption of the LP and came to have a ubiquitous presence on records in the 1950s and after. Many of the first liner notes mimicked the accompanying material found on classical 78-rpm albums that emphasized the biography, description, and background of the music and artist.Footnote 37 To those conventions, jazz records added personnel listings and other discographical information. As the genre developed, prominent jazz critics such as Leonard Feather, Nat Hentoff, Martin Williams, and Whitney Balliett all began writing liner notes while also writing for the best-known jazz publications. These trends coincided with increased attention to audio fidelity and recording technique as disc jackets began to display words like “high fidelity,” “in living stereo,” and “360 degree sound.”Footnote 38 In accordance with these practices, both World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece prominently display the words “A panoramic true HI-FI recording” on the top left of the cover, placed next to the record label logo and catalog number.

Along with this industry-wide change in format and design, cultural mediators such as label owner Granz, producers such as George Avakian, and Newport Jazz Festival co-founder George Wein increasingly targeted white middle-class audiences.Footnote 39 Granz issued records featuring Ella Fitzgerald singing popular standards accompanied by strings and placed his profitable Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) tours in large concert halls.Footnote 40 As the head of popular albums at Columbia Records, Avakian maintained an active jazz roster and successfully produced several crossover records featuring Dave Brubeck, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis. By co-founding the Newport Jazz Festival, Wein brought jazz to the affluent enclave of Newport Beach, Rhode Island. In 1956, the board of directors even changed the name of the festival (and its associated non-profit) to “The American Jazz Festival” and began referring to jazz as “a true American art form” in its promotional materials.Footnote 41 Around this time, the festival also gave the Voice of America broadcasting agency license to record and broadcast from the Newport grounds.Footnote 42

Against this backdrop, Granz founded Verve Records in 1956 with his eye toward the popular music market.Footnote 43 Granz initially conceived of Verve as a vehicle for Ella Fitzgerald, whom Granz had been managing since the mid-1940s.Footnote 44 Fitzgerald's early LPs on Verve each featured the repertoire of a different composer of the Great American Songbook. This organizational strategy took advantage of the 12-inch LP's capacity, which allowed for a single theme to be sustained through twenty-two minutes of uninterrupted music per side.Footnote 45 Granz succeeded beyond expectation. Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book, one of Verve's first LPs, became Fitzgerald's first top-selling record when it reached the number one position on the jazz charts in August 1956, several months before the release of Gillespie's World Statesman.Footnote 46 Between July 1956 and June 1957, Fitzgerald's Verve records overwhelmingly occupied the top position on the jazz bestseller list, while her name started appearing alongside Harry Belafonte, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, and Perry Como as a top “recording personality” of the day.Footnote 47

Verve's attempt to package jazz toward a broader audience was a success, at least financially. The label earned an estimated $2 million in sales in its first year and in 1957, Granz decided to unify his other labels, including Norgran and Clef, under the Verve banner.Footnote 48 All subsequent Gillespie titles, including Dizzy in Greece, appeared under the Verve imprint. The label also reissued many LPs from Norgran's catalogue, usually with no changes except an updated logo on the top right-hand corner of the album cover, as was the case with World Statesman.

The circulation of World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece coincided with Verve's founding, the record industry's total growth, and the rapidly expanding popularity of the LP format. The increased emphasis on the details of visual design—larger cover photos, more vibrant colors, the space for liner notes—made records audiovisual media. Using Norgran and then Verve as his platform, Granz took advantage of these industry changes to capitalize on Gillespie's role with the State Department and insert jazz into national debates about cultural diplomacy during the Cold War.

Gillespie's LPs and the Concert Tours

Both LPs explicitly equate the musical contents of the discs to the concert tours through the liner notes. “This album,” Stearns writes on World Statesman, “furnishes a sampling—volume two is yet to come—of the first half of the concert with Gillespie at his all-time best.” He classifies two pieces as “encores” and eventually concludes, “So ends the first album and the first half of the concert.” The notes on Dizzy in Greece take a similar approach: “This is the second album (the first was Dizzy Gillespie: World Statesman) of the music that piled up friends and momentum as it swung through the Middle East.”Footnote 49 To introduce his discussion of the music, Stearns writes, “The concert begins with the novelty HEY PETE, a Quincy Jones arrangement of the blues.” A draft of Stearns's liner notes to Dizzy in Greece concludes with a short statement, “The concert is over.” Though eventually cut, the sentence was meant to parallel the end of the notes on World Statesman. Footnote 50

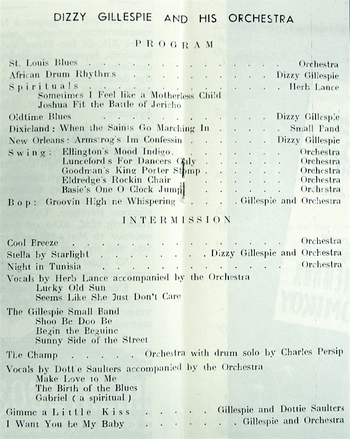

Surviving programs from Gillespie's Middle East tour make it clear that the LPs contain only a portion of the actual concert repertoire. Whereas the LPs features bebop-inspired arrangements of standards and original compositions orchestrated for the entire band, the Middle East tour concerts presented a much more varied selection of styles and ensemble configurations (Figure 1).Footnote 51 The first half of the concert featured a succession of performances intended to present an overview of jazz's historical development.Footnote 52 The band's two vocalists, Dottie Saulters and Herb Lance, neither of who appear on the LPs, sang African American spirituals, and Gillespie and drummer Charlie Persip demonstrated “African drum rhythms.”Footnote 53 The ensemble also performed various examples of blues and early jazz styles, including a Dixieland rendition of “When the Saints Go Marching In” and several note-for-note transcriptions of pieces from the swing bands of Jimmy Lunceford, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie.Footnote 54 “Groovin’ High” concluded the concert's first half as an example of the bebop style that Gillespie had helped make famous. The second half highlighted the band's modern repertoire and included several Gillespie originals: “Cool Breeze,” “The Champ,” and “A Night in Tunisia.” Along with various small group tunes, presumably played in the bebop style, the band also performed swing-era vocal numbers such as “Seems Like She Just Don't Care” and “Gimme a Little Kiss.”

Figure 1. Concert program from Greece tour, 1956. Program and notes, box 24, folder 22, 1956 Dizzy Gillespie Tour of the Near East, the Marshall Winslow Stearns Collection (MC 030), Rutgers University Libraries, Institute of Jazz Studies.

This programming served several purposes. The historical material educated audiences unfamiliar with the many types of jazz and its development.Footnote 55 Presenting the wide variety of sub-styles and reenacting historical big band charts told a musical story that started with jazz's earliest roots and arrived at Gillespie's modern style. Although jazz performance has always been historically self-referential, the explicit recreation of earlier styles was unusual in the mid-1950s.Footnote 56 This concert programming, originally a suggestion of Marshall Stearns, taught audiences various aspects of the music in an easily digestible narrative of progress and arrival.Footnote 57

In South America, where the band traveled to Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, the ensemble abandoned the historical portion of the program and added several newly composed arrangements in Gillespie's Afro-Cuban jazz style.Footnote 58 Along with performing “Manteca” and “Tin Tin Deo,” the ensemble's versions of “Begin the Beguine” and “Flamingo” also included newly arranged sections that heavily featured Afro-Cuban jazz rhythms. While on tour, the band also sought opportunities to play with famous tango artists in Buenos Aires and samba musicians in Rio de Janeiro. Argentinean pianist and future Hollywood composer Lalo Schifrin and trumpeter Franco Corvini were invited to travel and perform with the band as well. The hybrid musical styles showcased how jazz could be combined with other American musics, while the invitations for local artists to join the band demonstrated the musicians’ propensity for inclusivity and diversity.

The band's activities in South America were not included on the commercially produced LPs from the late 1950s. Record producer Dave Usher, a friend and former business partner of Gillespie's, accompanied the band in South America and recorded every concert the band played using a portable suitcase tape recorder.Footnote 59 According to Usher, he and Gillespie hoped the tapes might interest Granz on their return to the United States. Granz declined, but Usher kept the tapes, eventually issuing twenty-eight tracks across three CDs in 1999 and 2001.Footnote 60 The accompanying liner notes and credits include neither specific dates nor locations, yet the music remains consistent with several other live recordings of Gillespie's band from the same time period, including a Verve LP from the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival. As such, Usher's recordings give a sense of how Gillespie's band likely sounded during both tours.

A version of “Groovin’ High” recorded on location in South America illustrates how the band brought jazz history into the present through performance.Footnote 61 The ambassadorial band's arrangement pays tribute to Gillespie's bebop collaboration with Charlie Parker: the melodic content of the ensemble tags, solo transitions, and coda material, as well as the orchestration of the melody—unison trumpet and alto saxophone—originate from Gillespie and Parker's 1945 recording.Footnote 62 Gillespie based the harmony of “Groovin’ High” on a well-known standard from the 1920s titled “Whispering.” The concert program alluded this practice by expanding the title to “Groovin’ High ne [sic] Whispering.”Footnote 63 To make this historical connection aurally explicit, the saxophone section overlaid the original melody of “Whispering” (played in unison) onto Gillespie's composition (beginning at 0:30). Although bebop musicians often employed the harmony of songbook standards in this way, it was unusual to perform the original and newly composed melodies simultaneously.

In his demonstration of New Orleans jazz, Gillespie imitates the vocal and trumpet styling of Louis Armstrong on the band's version of “I'm Confessin’.”Footnote 64 During the spoken introduction and vocal scat breaks of the South American performance captured on Usher's tapes, Gillespie expertly mimics Armstrong's voice. For example, when Gillespie sings the word “but” he places a strong attack on the “B” in an Armstrong-like gesture (0:54). At other points, he imitates the elder trumpeter's propensity to end phrases with a long, sung “mmmmm” (0:17). Gillespie's trumpet style also pays tribute through half-valve attacks, shakes at the ends of phrases, extended high notes, and quotations of the song's melody. Fast bebop lines are notably absent. With its combination of humor and skill, the performance elicits laughter and strong applause from the audience.Footnote 65

“I'm Confessin’” concludes with a lengthy call and response between soloist and band. Gillespie executes a series of rising high notes (2:15):

Gillespie plays: Ab–Ab–C–Ab–C

Persip: Snare and bass drum hit. [pause] Band members: “Higher!”

Gillespie: Ab–C–C#–A–C#

Persip: Snare and bass drum hit. [pause] Band members: “Higher!”

Gillespie: A–C#–D–Bb–D

Persip: Snare and bass drum hit. [pause] Band members: “Higher!” Footnote 66

At this point, the melodic ascent ends and Gillespie holds his high D. Responding to another call for “higher,” he whistles the next note in the series; the audience laughs and cheers in response. Still in character, Gillespie starts chanting, “Gotta get one of those high Cs with the red beans and rice” and “high C, let's see, let's see where the high C is. Mmmmm” (2:52). He continues until the piano player answers a particularly loud outburst of “AHHHH” from Gillespie by playing the target, one step above Gillespie's last played note (3:32). After a few more moments of chatter, Gillespie asks the band, “You ready boys? Go ahead.” Another band member responds, “Are you ready?”, and Gillespie nearly breaks character before repeating his question. His final Ab–Ab–Db releases the built up tension and concludes the performance. Gillespie reclaims his regular stage voice to announce the next tune.

Gillespie's intelligence as a comedian and exuberant, onstage charisma were major reasons the musical advisory panel recommended him to the State Department in 1956.Footnote 67 With roots in the slapstick comedy of vaudeville, this jokester persona was an extension of the theatricality of other bandleaders such as Cab Calloway, who employed Gillespie between 1939 and 1941. Such onstage antics were, in fact, what gave him the nickname “Dizzy” during his time in the Frankie Fairfax band in the mid-1930s. Gillespie's expertly crafted version of Armstrong brought levity to a performance that originated from worldwide contestations over democracy and communism.

By matching novelty tunes, musical gags, and jokes with high-level musicianship, Gillespie offered an accessible and engaging performance to an audience unfamiliar with jazz. Several newspaper and magazine articles remarked on the overwhelming audience response. The Pittsburgh Courier, for example, characterized the reaction in Abadan, Iran, as a “miracle” when the audience began “awkwardly” clapping along. “Soon,” the article continues, “whistles and screams reached the stage.”Footnote 68 Stearns similarly reported that in Aleppo, Syria, some audience members would yell phrases like “rock it and roll it,” while others would “clap on the wrong beat, trying to figure out the proper response.”Footnote 69 In Ankara, Turkey, the band was “drowned out by the roar of the audience” that was “a solid wall of sound.”Footnote 70 Photos from the Middle East tour display large, over-packed concert halls with people visibly yelling, whistling, and dancing in the aisles.Footnote 71 Usher recalled a similar scene in South America, a claim substantiated by the audience on his recordings.Footnote 72

Gillespie's skill and flexibility exhibited an authority over the concert hall. Stearns describes how the “pandemonium” of the audience “ground to a halt only when the band started the Turkish national anthem followed by the Star Spangled Banner.”Footnote 73 The New York Amsterdam News and the Pittsburgh Courier similarly reported on the positive reaction to the band's performance of the Iranian national anthem.Footnote 74 Together, the paired anthems performed a notion of unity, a sentiment further accentuated by bilingual programs.Footnote 75 Writing for Down Beat, Stearns expressed the “pleased confusion caused by the fact that there are white as well as colored musicians in the band.” He also characterized the reactions of people across a wide spectrum of age, ethnicity, and nationality as “something universal.”Footnote 76 At various levels, the concerts challenged audiences to re-evaluate any preconceived notions of institutional racism within the United States. After all, how were these audiences to understand a black bandleader who spoke freely about racial politics and employed white musicians?Footnote 77

Even as these onstage actions pushed a narrative of progress toward an egalitarian future, Gillespie's emphasis on blues traditions, church spirituals, and the styles of New Orleans, Dixieland, and swing placed jazz within a historical trajectory of African American music. At the same time, the “African drumming” demonstration overtly tied the music to the transatlantic movement of African peoples through slavery.Footnote 78 Repurposing jazz history into the present shrewdly told a story that tied U.S. music to African American expressive culture. Through humor, playfulness, and musical expertise, Gillespie's onstage actions presented U.S. culture as inherently hybrid, diverse, and multinational. In doing so, he skillfully navigated an ideological space layered with politically charged discourses about communism, racism, and democracy.Footnote 79

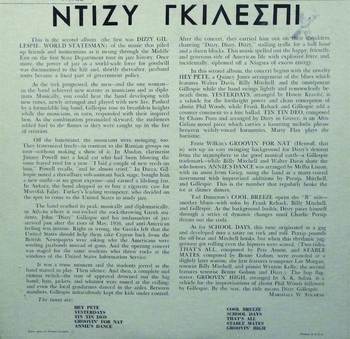

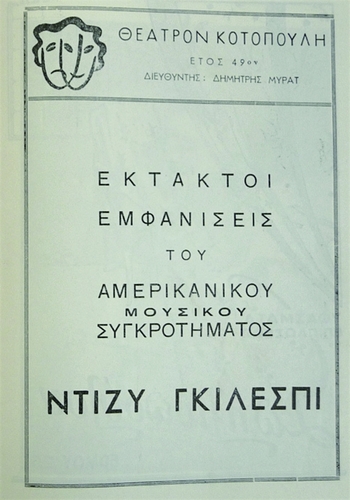

The LPs served a different purpose, as evidenced by the re-organization of materials as well as the musical minutia. Unlike the State Department tour concerts, the LPs included neither small group performances nor big-band vocal tunes. Gone too were the demonstrations of jazz's historical development and Gillespie's antics, jokes, and displays of humor meant to engage with audiences. Though the back of Dizzy in Greece replicated the Greek lettering of Gillespie's name from the concert program (Figures 2 and 3), the LP shared only two titles with the actual Greek performance: “Cool Breeze” and “Groovin’ High.”Footnote 80 The arrangement of “Groovin’ High” stayed mostly the same, except that the band omitted the “Whispering” melody meant to illustrate the song's origin.

Figure 2. Back of jacket with Greek lettering. Dizzy Gillespie, Dizzy in Greece, Verve MV-2630, 1957, LP.

Figure 3. Concert program title page, 1956. Concert program (Greece), box 24, folder 22, 1956 Dizzy Gillespie Tour of the Near East, the Marshall Winslow Stearns Collection (MC 030), Rutgers University Libraries, Institute of Jazz Studies.

Commercial considerations partially account for this difference because U.S. consumers were the LPs’ target market. Potential buyers would not need to buy a record of Gillespie playing Count Basie, for example, when he or she could easily buy an LP of Basie's own band on the same record label. For their U.S. performance in the middle of 1956, as Nat Hentoff wrote in Down Beat, the ensemble had to scramble for arrangements because “half of the band's overseas program was concerned with a historical recapitulation of jazz, a documentary which would not have been usable for American club dates.”Footnote 81 The LPs’ target audience paralleled that of the club date Hentoff mentions.

However, market factors do not completely explain the dissimilarities between Gillespie's ambassadorial LPs and the tour concerts. After all, another Verve LP from 1957 featuring the same ensemble, Dizzy Gillespie at Newport, includes several moments of Gillespie's musical humor and onstage antics.Footnote 82 The band's Newport rendition of “Doodlin’,” for example, ends with an impromptu call and response between band members. During the restatement of the theme at the end of the chart, baritone saxophonist Pee Wee Moore purposefully misplays his highly exposed melodic line. Pianist Wynton Kelly responds with a jagged extrapolation of the melody; the band laughs and Gillespie shouts, “Hey!” (5:23). Moore plays his melody again with an over-exaggerated vibrato, as if mocking Gillespie. The rest of the band mimics this humorous vibrato, creating a noticeable reaction from the Newport audience (6:24).Footnote 83

By omitting the moments of humor, spoken introductions, and interactions with the audience, World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece present Gillespie's music as serious political work. The second LP, Dizzy in Greece, for example, placed the band within the cradle of white European civilization, visually accentuated by the photo of Gillespie adorned in the white fustanella and positioned against the Greek temple columns.Footnote 84 While the tour concerts told a story about jazz, racial progress, and the importance of African American music to U.S. culture, the LPs removed any direct ties to African American expressive culture by omitting the performances of African drumming, African American spirituals, blues practices, and New Orleans second line traditions. The “whitewashing” of the band's activities on tour presented jazz to white, mainstream U.S. audiences by adopting a language of racial uplift and respectability. In doing so, the LPs appealed to Western European values of concert music through their audiovisual production and design.

Marshall Stearns Drafts his Liner Notes

The aggressively uneven political climate in which jazz operated at this time was on display during three congressional hearings in June and July of 1956. Representative John Rooney and Senator Allen Ellender, in particular, forcefully questioned Theodore Streibert, director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and coordinator of the Cultural Presentations program, about the validity, effectiveness, and cost of the jazz programming.Footnote 85 During the House Appropriations Subcommittee meeting, Rooney pointedly asked Streibert about Gillespie, “Do you think it is a good expenditure of Government funds to allocate $5,000 in connection with Dizzy Gillespie?” After correcting the dollar amount, Streibert spoke positively about the first jazz tour: “$4,400, yes. Yes, sir, I think so. There is an enormous interest in American jazz bands, which is a great resource of this country.”Footnote 86

Unconvinced, the House committee voted to cut the project's proposed budget in half, from 9 to 4.6 million dollars. A few weeks later, on 9 July, Streibert appeared before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee and asked the Senate to restore the original budget. Resistance came from Senator Ellender of Louisiana:

Ellender: Now, I notice that you have also increased the amount for cultural activities; that is, to send orchestras abroad, and things like that.

Streibert: Yes, sir.

Ellender: Do you think that is beneficial? Let me have it straight.

Streibert: I will say this: I am in the business now of spending money to make an effect on public opinion abroad. I want to say that, in my opinion and from my experience, there is nothing we have spent that has produced such an effect per dollar spent as is sending of orchestras, of performers, of Porgy and Bess, of various kinds of individuals, particularly in the Near East, South Asia, and Far East, as this cultural program. It has paid off big dividends.

Now, I base that on reports from the posts, but I base it also on what our Ambassadors say, not what our own people in the Information Agency tell me, but what Ambassadors report back to the State Department.

Ellender: What reports did you get on the presentation of Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra? I heard it at one of the President's big dinners, I think, and I never heard so much pure noise in my life. They said that they played in Turkey and Rome and Paris, and I am wondering what good you got out of that.

Streibert: Well, sir, jazz is one of our resources. It is one of our assets. We are just starting to use it. We have been using it on the air very successfully in a program of music from America which has been widely listened to in Eastern Europe.Footnote 87

Streibert went on to cite a positive press account as well as a glowing review from a Beirut dispatch. Undeterred, Ellender continued his hardline questioning:Footnote 88

Ellender: Did you get any criticism?

Streibert: No, sir.

Ellender: None whatever?

Streibert: No, sir. There has been criticism that people have been unable to get tickets and get in. They have been very generous in giving extra performances and playing at private affairs. I read the dispatches from Istanbul and they are similarly ecstatic. Not everybody likes jazz. Probably you are among those who do not.

Ellender: It is not a question of liking it. When I first voted for this measure, as you remember 2 years ago, the idea was to put forth that the people of England and France and Western Europe thought we were barbarians. That is in the record. I remember it. And it was brought out that we ought to counter that by sending in our own cultural orchestras and what have you.Footnote 89

Ellender ends this portion of the discussion by unequivocally stating his view: “I say it does more harm than good to send some of this abroad, in my humble judgment.”Footnote 90 In a press account soon after, he repeated his assertions regarding Gillespie: “To send such jazz as Mr. Gillespie, I can assure you that instead of doing goodwill it will do harm and the people will really believe we are barbarians.”Footnote 91 Along with his description of Gillespie's music as “noise,” Ellender uses language with racist overtones to differentiate jazz from orchestral music, which he finds to have more social and cultural validity.

As this testimony attests, disagreements over the funding for the Cultural Presentations program placed jazz and its practitioners in the middle of a cultural war over domestic and international Cold War policy. For his part, Gillespie embraced the public and highly political platform. In response to negative press reports about the congressional hearings, Gillespie sent a widely publicized telegram to President Eisenhower in August 1956:

Shocked and discouraged by decision of the Senate in the supplementary appropriation bill to outlaw American jazz music as a way of making millions of friends for USA abroad. Our trip thru Middle East proved conclusively that our interracial group was powerfully effective against Red propaganda. Jazz is our own American folk music—the communication with all people regardless of language or social barriers. I urge that you do all in your power to continue exporting this invaluable form of American expression of which we are so proud.Footnote 92

Gillespie emphasized jazz's wide popularity across social strata as well as its inherent connections to U.S. culture. He also stressed the “folk music” appeal to assert that the music could connect with world populations through an art form unique to the United States.Footnote 93 In several respects, Gillespie's comments echoed several proponents of the Cultural Presentations program. Streibert, for example, told the House committee that jazz is a “great resource of this country” and, in a written statement to the same committee, Representative Frank Thompson depicted jazz as a “cultural weapon” for which the United States “has a copyright.”Footnote 94

Like Gillespie and others, Marshall Stearns also advocated for jazz's place in the Cultural Presentations program through various channels of print media, including his liner notes to World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece.Footnote 95 As archival documents attest, Stearns presumably drafted these liner notes in conjunction with one another sometime between July and early September 1956 while debates raged over the State Department's use of jazz overseas. Several documents outline Stearns's overall strategy toward both LPs. World Statesman, as one handwritten note states, should take a “more general approach on Gillespie's effectiveness abroad.” The same document also includes a track listing for Dizzy in Greece that includes seven pieces, all of which appear on the final LP.Footnote 96 Significantly, the three tracks recorded at a later session in April 1957—“That's All,” “Stablemates,” and “Groovin’ High”—are not mentioned here or on Stearns's typed draft of the Dizzy in Greece liner notes. The published version of the notes is identical to Stearns's draft with one exception: a parenthetical phrase was added to account for the three tracks not mentioned in the draft.Footnote 97 The 1956 date of these notes is further confirmed by a header in a separate document:

-

“Dizzy in Greece” 12 inch

-

Liner for Granz

-

Due Sept 7 airmailFootnote 98

Although no year is stated, the airmail due date likely refers to September 1956. Stearns's notes never mention material from the later session in April 1957 yet always accurately describe the other tracks in detail. Moreover, plans that outline the structure and contents of each LP often appear in the same document and seem to have been drafted at the same time.Footnote 99

Stearns conceived of both sets of liner notes as doing the same type of political work. A skeleton draft of the Dizzy in Greece liner notes makes it clear that Stearns wanted to foreground anecdotes from the band's tours in order to present Gillespie's travels as a triumph. Consider this brief outline:

-

1. range and overall success

-

2. Dacca—an example

-

3. Thru it all . . . Diz as diplomat: mixed band, Ankara, snake charmer

-

4. why they loved it—generous etc.

-

5. ′′—real art

-

6. ′′—freedomFootnote 100

By connecting the words “generous” and “freedom” to audience reception, Stearns aimed show how jazz cultivated political goodwill for the United States, a common theme in both liner notes. In total, Stearns appears to be answering a question posed in a handwritten note found in the margin of one of these drafts: “Topic: Is jazz good propaganda?”Footnote 101

Not by coincidence, this question was also the title of an article Stearns published in the Saturday Review on 14 July 1956.Footnote 102 Circulating two months after Gillespie's ensemble completed the first tour and before the release of World Statesman, the article argues for jazz's validity as a diplomatic tool. The music, Stearns writes, could “communicate more of the sincerity, joy, and vigor of the American way of life than several other American creations inspired by Europe.”Footnote 103 Elsewhere in the article, he accentuates jazz's relationship to the “American way of life.” “On the surface,” he declares, “everybody—even the old folks—seemed to want to love jazz, even before they heard it. They definitely associated jazz with the cheerful, informal, and generous side of American life and they were bowled over by its spontaneity and vitality.”Footnote 104

The article, both in tone and content, was the basis for Stearns's liner notes to World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece. Both liner notes link Gillespie's onstage performance to current events in order to argue for jazz's political relevance and convince listeners that jazz's value extends beyond U.S. borders because of the music's ability to overcome cultural difference.Footnote 105 In the notes to World Statesman, for example, he asserted that the band's “team-spirit” actively “spells out a new kind of freedom. Maybe that is why jazz is America's best-loved cultural export.”Footnote 106 By metaphorically referring to the movement of goods across national boundaries, Stearns links jazz to the entrepreneurial spirit at the center of U.S. capitalism while his emphasis on the music's “vitality” associates the music with democratic ideals of progress, action, and freedom.Footnote 107

Several stories appearing in both the liner notes and the Saturday Review article attempt to demonstrate the “generous side of American Life,” a reoccurring phrase meant to explain how Gillespie's music reached local populations.Footnote 108 Saxophonist Jimmy Powell, for example, donated reeds to a local musician, and Gillespie apparently quoted phrases from “Ochi Chornia,” a famous Russian folk song, as a nod towards the Russian Folk Ballet members in attendance at one performance.Footnote 109 Other stories directly addressed the tour's cultural politics. In one memorable anecdote, Gillespie invited a snake charmer into his room despite vigorous objections by hotel management; another describes Gillespie's refusal to play a concert in Ankara, Turkey, until the street children standing outside the gates were allowed to attend. Both World Statesman and Stearns's article quote Gillespie's explanation: “I came here to play for all the people.”Footnote 110 Altogether, Stearns establishes that Gillespie's version of diplomacy meant sharing his music with everyone, regardless of social, economic, or ethnic position. Jazz, in this view, unifies people through its capacity to engage peacefully across difference while also respecting individual forms of expression.

The idea of jazz's moral imperative can also be seen in Stearns's first monograph, The Story of Jazz, published in 1956, around the same time as World Statesman.Footnote 111 The book portrays jazz as a uniquely “American” contribution to the world. “Jazz,” he writes in the introduction, “has played a part, for better or worse, in forming the American character.”Footnote 112 One of the later chapters focuses on Gillespie's State Department tours and describes the music as a “secret sonic weapon” in the war against communism.Footnote 113 In “win[ning] over the people,” he writes, “the friendly and free wheeling band . . . led many people to abandon their communist-inspired notions of American democracy in the course of one concert.”Footnote 114

Stearns's presentation of Gillespie as a symbol of national pride and racial harmony also fit within Granz's worldview of jazz and its potential to enact social change. Beginning in the 1940s, Granz included an anti-discrimination clause in his contracts that guaranteed desegregated audiences, even while traveling in the South.Footnote 115 When he first presented the jam-session style concerts under the Jazz at the Philharmonic banner in 1944, he did so as a benefit for twenty-one Mexican youths convicted of crimes committed during the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943. That same year, he organized concerts to support the Fair Employment Practices Commission and other organizations fighting for anti-lynching legislation.Footnote 116 His business acumen provided a steady stream of concerts, recordings, and promotional opportunities for his musicians. Yet even as one of the jazz industry's most successful entrepreneurs, he always conducted his business with a politically conscious edge.Footnote 117

When Norgran issued World Statesman at the end of 1956, Granz no doubt considered it smart business practice to take advantage of Gillespie's national exposure as an active agent on the Cold War's front line then circulating through the various print media. He also recognized how his primary business, selling records, could interact with the culture of print-capitalism that, as Benedict Anderson famously argues, is vital to constructing the nation-state.Footnote 118 With these recordings, Granz seemingly took advantage of the moment in order to present Gillespie to a broad audience and place jazz on a national stage where discourses of racial discrimination and unequal citizenship were in continuous circulation.

Conclusion: Dizzy the Diplomat

During an onstage moment in an unidentified South American city, Gillespie unexpectedly catches himself playing the straight man. “And now ladies and gentleman,” he begins a bit stiffly before pausing and commenting to himself, “Oh, I'm out of character.”Footnote 119 This admission, however brief, testifies to his awareness of what it meant to be “in character” while on stage. Whether during a spoken introduction or while improvising during within a tune, Gillespie's performance was not simply about music making, but was also a way to transmit cultural knowledge, memory, and citizenship through embodied action.Footnote 120 Indeed, his creativity on and off the bandstand helped him negotiate the shifting political landscape of jazz during a crucial time of upheaval on a worldwide stage.

As Gillespie and others clearly realized, the use of jazz as a weapon against Soviet propaganda through unprecedented support from the U.S. government presented an opportunity to raise the music's profile and cultural positioning. Gillespie's LPs, as one small piece of the puzzle, invariably engaged with domestic debates about civil rights within the United States. As a result, the LPs’ content became less about what actually took place on the tours and more about making the music legible to U.S. audiences not already invested in jazz for its own sake. Here, the omission of any reference to the South American tour looms large. By only including Gillespie's activities in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, the LPs purposefully appealed to the stature that Europe still maintained with U.S. audiences. The records explicitly portrayed themselves as a jazz “concert” without Gillespie's vocal commentary or characteristic humor. This marketing strategy toward a political end can also be seen on the cover of Dizzy in Greece, with Gillespie in his white fustanella, leaning against the pillars of a temple that had resiliently stood the test of time. By implication, the music should as well.

The discrepancies in repertoire between the LPs and tour concerts speak to the different kinds of political work each was attempting to accomplish. The tours’ success depended on collaboration between an interracial group of musicians and the nation-state that, on stage, performed a positive version of U.S. culture for local populations. Gillespie used this opportunity to stage an inherently hybrid and diverse vision for the United Sates, one that foregrounded African American expressive culture. The LPs told a related but different story about jazz and its political effectiveness in the world. The jazz tours were a start, but it was equally important for U.S. audiences to understand jazz as a participant in the serious business of diplomacy. The LPs rendered jazz as “American” music through their audiovisual design, depicting Gillespie as a dignitary fit for the resolute work of an ambassador.

Reading this political moment through the overlapping structures and networks of the music business points to how the circulation of performance on record attempted to shape the discourse surrounding jazz and musical diplomacy. The industry's adoption of the 12-inch LP and the resultant increase of sales across a wide spectrum of consumers made the musical format into a media of mainstream popular culture during the mid-1950s. These changes greatly influenced Granz as he positioned Verve within the already well-established channels of print-capitalism, especially those publications aimed at middle-class white audiences. Recordings such as Gillespie's became visual, aural, and physical representations of the political moment, moving jazz into a contested arena of mid-century U.S. culture. World Statesman and Dizzy in Greece, as two 12-inch black vinyl records, were objects through which the abstract connection between jazz and the nation-state materialize.Footnote 121

Both LPs adopted the same language and rhetorical strategies as other forms of print media covering Gillespie's ambassadorial tours. These records attempted to make Gillespie's music audible to the various strata of U.S. culture by convincing listeners of jazz's import and relevance. Recall the first words of Dizzy in Greece:

This is the second album (the first was DIZZY GILLESPIE: WORLD STATESMAN) of the music that piled up friends and momentum as it swung through the Middle East on the first State Department tour in jazz history. Once more, the power of jazz as a world-wide force for goodwill was documented to the hilt and, shortly thereafter, jazz band tours became a fixed part of government policy.Footnote 122

Using Gillespie's activities as evidence, the LPs stress the historical significance of jazz's use in an official capacity by the State Department for the first of many times to come. Because the tours ultimately survived the public debates about the merits of jazz diplomacy, as well as a forceful pushback from Congress, the notes at once celebrate Gillespie as a trailblazer and as a political victor. In this way, both LPs were not objects of the past, but media that imagined jazz's future.