Introduction

Secession is a phenomenon that affects both developing countries (e.g. Georgia, China, Russia, Ukraine, Nigeria) as well as developed ones (e.g. Spain, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Italy). In several European democracies, like the United Kingdom and Spain (Muñoz and Guinjoan, Reference Muñoz and Guinjoan2013; Muñoz and Tormos, Reference Muñoz and Tormos2014), secessionist demands are accompanied by calls for a referendum to decide the question once and for all. In others, such as France, Belgium, and Italy, secession is at least sporadically invoked in political discourse when demanding more territorial group rights or fewer payments to poorer areas (Coppieters and Huysseune, Reference Coppieters and Huysseune2002; Lindsey, Reference Lindsey2012).

Despite these developments in European politics, scholars continue to disagree over the relative importance of different mechanisms for understanding secession. Some argue that cultural factors, such as emotions, affect, and social identity, are key to explaining nationalism and separatism (e.g. Smith, Reference Smith1986; Connor, Reference Connor1994; Petersen, Reference Petersen2002), whereas others think that they can best be understood in terms of rational action (e.g. Buchanan and Faith, Reference Bühlmann and Caroni1987; Wittman, Reference Wittman1991; Bookman, Reference Bourdieu1992; Bolton and Roland, Reference Bookman1997; Collier and Hoeffler, Reference Collier and Hoeffler2002; Sorens, Reference Sorens2012). Still others emphasize structural constraints on individual decision-making through geographically constrained social networks (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986; Lipset and Rokkan, 1990 [Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967]; Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Harmon, Werfel, Gard-Murray, Bar-Yam, Gros, Xulvi-Brunet and Bar-Yam2014). Thus, whereas some scholars see secession as largely a matter of the heart, others see it as structurally determined, and others have given pride of place to the head in making such decisions.

In this article, we contend that neither cultural, rational nor structural approaches by themselves are sufficient to account for secession. Consistent with research in historical institutionalism (Steinmo et al., Reference Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992; Katznelson and Weingast, Reference Katznelson and Weingast2005; Steinmo, Reference Steinmo2008), we conceptualize these explanations as inextricably linked. Specifically, we argue that whereas a cultural logic can account for the origin of political preferences, and structural approaches explain the constraints on decision-making, rational accounts can predict how actors behave when attending to these preferences in the face of ecological constraints. A more complete understanding of the determinants of separatism thus requires taking all of these logics seriously. The theory presented here stipulates that cultural identities matter by shaping political preferences for more or less statism, which in turn informs voting behavior on secession together with ecological factors. Hence, we identify one (but not the only) possible mechanism by which cultural identity influences secessionism through its effect on political preferences for statism (cf. Sorens, Reference Sorens2012). By statist political preferences, we mean preferences pertaining to the general purpose of government, ranging from only minimal interventionism to maximal provision of public goods (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1991). By ecological factors, we are referring primarily to arguments that discuss how geography and topography shape social networks, information flow, collective action, and decision-making (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986).

To test these claims while accounting for alternative explanations, we analyze the results of a referendum held on 24 November 2013 in the Swiss region of Jura Bernois. The vote concerned whether this region with some 50,000 largely French-speaking and Protestant inhabitants should leave Canton Berne (a largely German-speaking and Protestant entity with 900,000 inhabitants) to join Canton Jura (a predominantly French-speaking and Catholic entity with 70,000 inhabitants). Although the secession of that region from Berne Canton was eventually defeated (72% against vs. 28% in favor), the referendum results exhibited considerable variation across the 49 municipalities with a spread of >50% points (from 2% up to 54% in favor).

The next section examines existing theories that might help us to explain variation in the vote on secession, and then presents our own theory. We then apply these reflections to the situation at hand and explain our case selection. Next, we present our methods and data, and discuss the main findings. The final section concludes with some general implications and avenues for further research.

Theory

The large literature on secession can be usefully divided into three main approaches. The first is a culturalist approach that emphasizes the role of shared values in shaping political behavior (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1965; Smith, Reference Smith1986; Connor, Reference Connor1994). On this account, Dutch-speakers (e.g. in Flanders) should want to live with and be ruled by other Dutch-speakers, and Catholics (e.g. in Northern Ireland) should aim for the same. The implication is that individuals prefer to be ruled by natives rather than by cultural aliens (Hechter, Reference Hechter2013). Moreover, people tend to carry these supposedly immutable identities with them when they move, at least in the short run, rather than adapting to their new cultural context (Connor, Reference Connor1994). Thus, the immigration of people with a specific cultural background may influence the strength of a particular cultural marker, thereby shaping the demand for separation or unification on the basis of that identity.

The second approach is rationalist. Researchers in this tradition typically focus on the economic consequences of secession for individuals (e.g. Buchanan and Faith, Reference Bühlmann and Caroni1987; Wittman, Reference Wittman1991; Bookman, Reference Bourdieu1992; Bolton and Roland, Reference Bookman1997; Nadeau et al., Reference Nadeau, Martin and Blais1999; Collier and Hoeffler, Reference Collier and Hoeffler2002). Another rationalist stream of research asserts that the relative position of groups in the stratification system privileges certain social identities over others (Hechter, Reference Hechter1978; Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1985; Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2002; Cederman et al., Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013). Thus, when a cultural group is relegated to a subordinate position in the stratification and political systems, this affects its members’ life chances, thereby intensifying the political salience of the cultural marker that is associated with their subordination. When full inclusion appears unlikely or cannot be offered credibly, the subordinate group may demand more self-rule (Sorens, Reference Sorens2012).

The last approach is structuralist. Some of these accounts are based on the idea that the social networks that facilitate collective action are fundamentally constrained by geographic factors, such as distance and topography (Rokkan and Urwin, Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986; Lipset and Rokkan, 1990 [Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967]; Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Harmon, Werfel, Gard-Murray, Bar-Yam, Gros, Xulvi-Brunet and Bar-Yam2014). For example, the greater the distance from a center to its peripheries, ‘the greater the risk that these will become the nuclei of independent center formation’ (Rokkan and Urwin, Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983: 16), hence the looser the bonds that tie the two together and the more likely secession is to occur. Whatever their origin social networks may promote in-group altruism that fosters collective action [but see Simpson et al. (Reference Simpson, Brashears, Gladstone and Harrell2014) for some disconfirming evidence].

These three explanations – cultural, rational, and structural – are all plausible but incomplete accounts for secession.Footnote 1 Why, for instance, do people who share multiple cultural identities (each of which might become politically relevant) emphasize one over another when a choice is required? The Swiss case presents us with a situation in which people are deciding whether to remain a linguistic minority or to become a linguistic majority but a religious minority. Cultural logic seems unable to specify which of these different identities serves as the basis for political identification and decision-making. Nor can a cultural approach easily explain why a group’s linguistic identity trumps its religious identity in some situations but not in others, or why there is a change in political salience over time and in different contexts, or when multiple identities might be mutually reinforcing rather than cross-cutting or conflicting. The problem is that most studies of ethnic, linguistic, and religious conflict take the existence of cultural differences for granted. However, as individuals almost always possess multiple social identities (e.g. Simmel, Reference Simmel1955; Roccas and Brewer, Reference Roccas and Brewer Marilynn2002), this practice is questionable and the assumption of cultural differences that matter politically must itself be explained (Posner, Reference Posner2004). Moreover, the mechanism of cultural homophily (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Brashears, Gladstone and Harrell2014) may not be the only, or the most important, reason for the political effects of cultural identities: to have an effect, cleavages also need to be activated by political entrepreneurs (Rokkan and Urwin, Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983; Lipset and Rokkan, 1990 [Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967]).

Rationalist approaches suffer from their own shortcomings. First, all rationalist analyses take cultural identities for granted, treating them as exogenous to their explanatory apparatus, even though such identities are themselves the product of other processes and factors and may change over time and contexts. Second, although rationalists typically assume that the demand for secession emanates primarily out of instrumental – that is, economic – considerations (Sambanis and Milanovic, 2014), sometimes pocketbook issues only play a minor role (Toft, Reference Toft2012: 586). As Horowitz notes, in some cases ‘the decision to secede is taken despite the economic costs it is likely to entail’ (Reference Horowitz1985: 237, emphasis added; cf. Loveman, Reference Loveman1998). Finally, although structural constraints such as distance and topography affect network formation and limit the choices available to individuals, there is no warrant to believe that they are the sole or main determinants of political behavior, for individuals in similar structural positions can – and often do – exhibit disparate behavior.

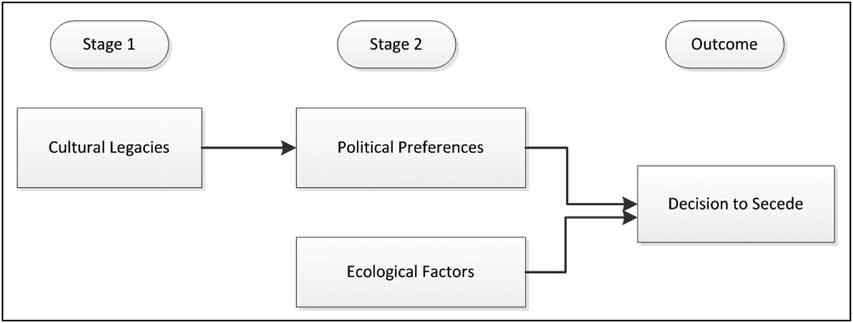

We argue that these approaches require integration, as culture explains the origin of political preferences; spatial features such as topography and distance shape interaction opportunities, thereby reinforcing or undercutting preference homogeneity; and rationality explains the choices made on the basis of the resulting preferences. Figure 1 depicts this framework schematically.

Figure 1 Two-stage theoretical model.

At the left of the figure are cultural legacies [or what Bourdieu (Reference Brubaker1977) terms habitus], which we hypothesize shape political preferences. These legacies comprise the lifestyle, values, dispositions, and expectations of particular social groups that are acquired through the activities and experiences of everyday life (Nisbett and Cohen, Reference Nisbett and Cohen1996; Alesina and La Ferrara, Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000; Talhelm et al., Reference Talhelm, Zhang, Oishi, Shimin, Duan, Lan and Kitayama2014).Footnote 2 For example, it has long been appreciated that some religious groups have more individualistic values, whereas others are more collectivist (Durkheim, Reference Durkheim1951; Davis and Robinson, Reference Davis and Robinson2012). Collectively oriented religions, such as Catholicism, tend to view the state as a vehicle that has a moral responsibility to protect the most vulnerable members of society. In general, Catholics have a greater taste for redistributive welfare policies, and for a moralistic foreign policy, than Protestants (Castles, Reference Castles1994). By contrast, more individualistic religions, like many Protestant denominations, emphasize hard work and individual responsibility, which they believe promotes independence and self-reliance, over state-provided welfare. It follows that the resulting policies from this tradition favor equality of opportunity over redistribution.Footnote 3

However, religion is far from the only source of political preferences. Language groups may also confer specific political preferences. Consider the two relevant languages in our empirical analysis: German and French. It is widely appreciated that France has a much stronger tradition of statism and centralization than Germany, a federal country with ample regional differences in wealth, policy, and history. By the same token, Francophone areas of bi-national states such as Belgium are often more left-leaning than their English- or Dutch-speaking counterparts, which helps to explain why the Socialists are the major party in Wallonia but not in Flanders (Deschouwer, Reference Deschouwer2009: 127–132). Similarly, ‘Quebecers’ collective identity is defined around specific political values mostly associated to the left of the political spectrum’ (Bühlmann and Caroni, 2013: 222). In Switzerland, too, French-speakers are regarded as more open to Europe and the world, and more in favor of social redistribution as well as state intervention, than German-speakers (Linder et al., Reference Linder, Zürcher and Bolliger2008: 63, 186; Bühlmann and Caroni, 2013).

The contrast becomes even stronger when comparing Berne Canton (predominantly German-speaking and Protestant) with Jura Canton (predominantly French-speaking and Catholic). For example, at the federal parliamentary elections of 2011 (elected using proportionality), in Jura the Christian-Democrats came first, with 33.2% of the vote, followed by the Socialists, with 30.8%. In Berne, by contrast, the national-conservative People’s party came first, with 29%, followed by the center-right party BDP (Bürgerlich-Demokratische Partei), with 14.9% [Bundesamt für Statistik (Federal Statistical Office) (BFS), Reference Bieber2015]. Also note that, particularly with regard to social welfare, Swiss Christian-Democrats have moved to the left, while right-wing parties are staunchly pro-market (Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014: 598f.). Accordingly, in Armingeon et al.’s (Reference Armingeon, Bertozzi and Bonoli2004: 35) classification of cantonal ‘worlds of welfare’, Berne belongs to the liberal-conservative type whereas Jura is predominantly social-democratic.

According to our theory, ecological factors can either enhance or detract from this effect of cultural legacies on political preferences. When ecology serves as a barrier to intra-group interaction, the effect of cultural legacies on political preferences is attenuated. For example, a mountain range may cut off an otherwise homogenous territory and produce separate ways of life and political preferences. Likewise, due to residential sorting, people born in the same city may have opposite political preferences based on exactly where they live in it (Cox, Reference Cox2002: 148). However, when ecology facilitates intra-group interaction, the effect of cultural legacies is reinforced. Research on cross-border regions confirms that ‘physical proximity […] has less to do with pure distance measured in kilometers between different actors, than with the efforts it takes for them to interact in terms of time and costs’ (Lundquist and Trippl, Reference Lundquist and Trippl2013: 53). Related to proximity are more material and practical concerns, including economies of scale and spillover effects, for example job opportunities (in public administration in Delémont, which would grow and become more influential in an expanded Jura), and exposure to common news outlets (Lundquist and Trippl, Reference Lundquist and Trippl2013).

Once political preferences have been formed, our model predicts that people then act based on those preferences, given ecological constraints. In our case, it is statist preferences that primarily shape the decision to secede. When current state policy is largely congruent with the values of particular cultural groups, these groups can be considered to be more or less politically satisfied, and they are therefore oriented toward the status quo and non-secession. But when state policies are at variance with the preferences of cultural groups, then some political tension is bound to occur (Alesina and La Ferrara, Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000). Hence, when afforded the opportunity to choose, as in secession referenda, cultural groups will prefer to be ruled by those who share their values rather than by the representatives of groups espousing different values, all else equal. Being ruled by those with different preferences about the role of government can be perceived as alien rule and therefore illegitimate (Hechter, Reference Hechter2013). It is illegitimate not only because it violates the pervasive norm of collective self-determination (as advanced, e.g., in the United Nations Charter), but also because the former group usually suffers from sub-optimal governance at the hands of alien rulers. Hence, minority language groups typically desire state recognition of their language; members of minority religions claim the same as regards their faith, and so forth. This kind of demand lies at the heart of all nationalist and secessionist movements (Hechter, 2000). Hence, were it given the choice, every distinctive cultural group should prefer to be ruled by its own kind rather than by cultural aliens. Indeed, ethnic voting around the world is pervasive, especially in multinational African and Asian countries, but also in Europe. The first elections in Bosnia in 1990, for example, were deemed ‘indistinguishable from an ethnic census’ (Bieber, Reference Bolton and Roland2006, table 2.7). Many elections around the world are similar, even in societies that are not war-torn.

Next, we apply this theoretical model to the case of Jurassic separatism.

Why Jura Bernois chose not to secede

On 24 November 2013, a majority of 72% in the Jura Bernois region of Switzerland voted to remain in the Canton of Berne. With an average turnout of 76% across the 49 municipalities concerned, and one even attaining 97%, people clearly cared enough to vote on this issue.Footnote 4 The outcome of the referendum revealed that people value the status quo, in which they are a tiny linguistic minority of 6% in a large canton with 900,000 inhabitants, over one in which they would have been a substantial religious minority of 42% in a medium-sized canton of 120,000 inhabitants after unification. This begs the question: Why was religious homophily with the rest of Berne more important for Jura Bernois than linguistic homophily with Jura, when joining Jura would have increased the group’s relative size, and presumably its political influence?

Once we take into account the history of Switzerland, the puzzle becomes even more intriguing. When the Swiss polity was reshaped in the wake of the Napoleonic wars during the Congress of Vienna in 1815, several of the pre-1798 cantonal powers were restored, but with significantly reduced territorial borders. This was particularly the case for Canton Berne, whose extensive territorial losses to the North and South were compensated by awarding it the former Prince-Bishopric of Basel in its North-West, on the border with France (Mueller, Reference Mueller2013: 94). Following a history of post-WWII political mobilization, leading up to a referendum cascade at the regional, district, and local levels between 1974 and 1975, the predominantly French-speaking and Catholic region in very North-West of that area seceded from the predominantly German-speaking and Protestant Canton of Berne to form the Canton of Jura (Laponce, Reference Laponce2012: 124–126; see also Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986). Yet, the Jura Bernois region chose to remain part of Berne rather than join the new Canton of Jura in 1974 (Crevoisier, Reference Crevoisier2012). Despite this initial rejection, the architects of the new Canton of Jura continued to campaign for a unified French-speaking canton (Rennwald, Reference Rennwald1995; Ganguillet, Reference Ganguillet1998; Pichard, Reference Pichard2004).

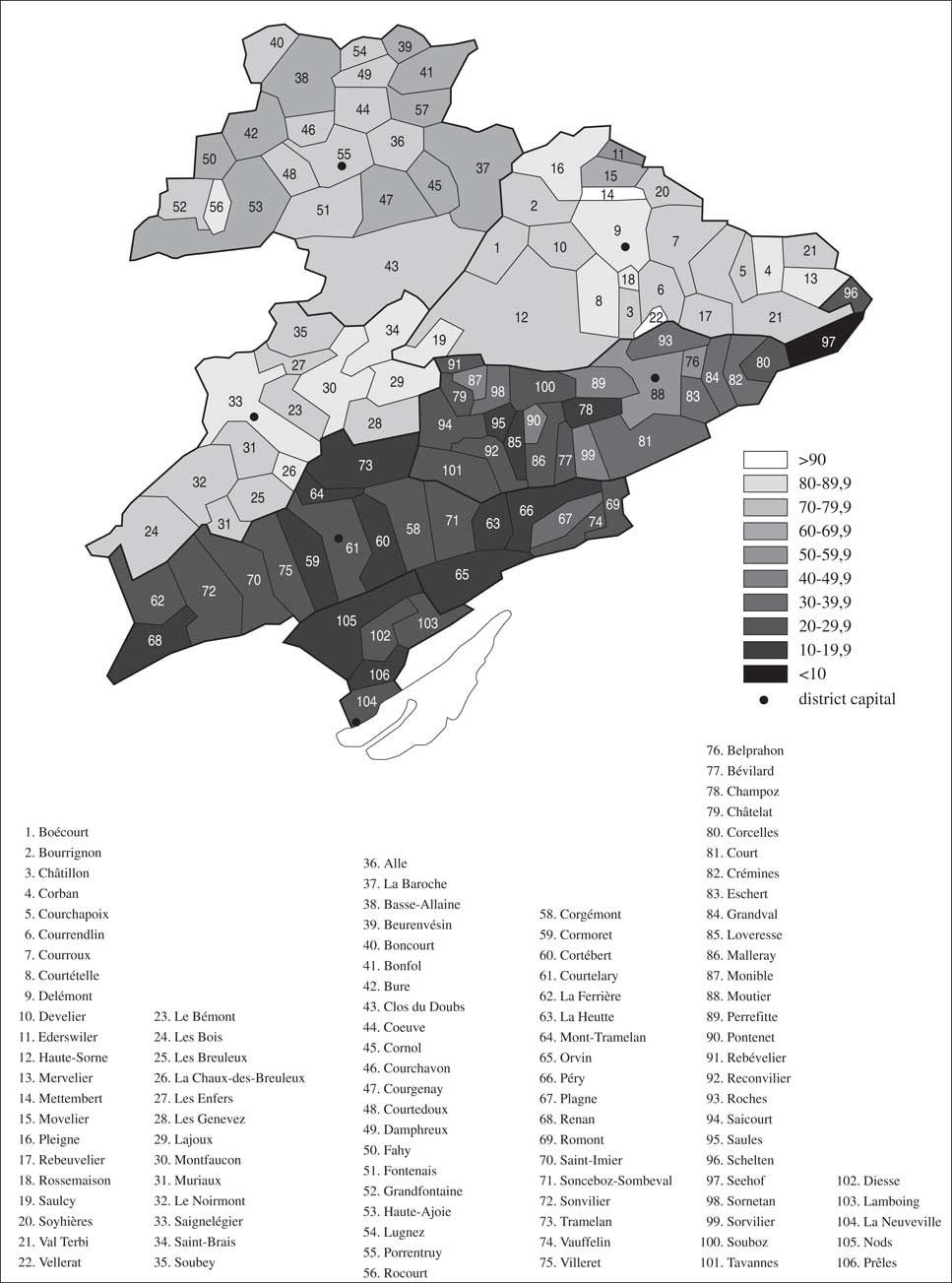

After 40 years of political struggle, the elite of Jura managed to hold a new referendum on the unification of Francophones in Jura Bernois and Jura Canton (Schumacher, Reference Schumacher2005). The 2013 referendum took place in the two areas, Jura Canton and Jura Bernois, and asked whether voters in these two regions wanted to initiate a process whereby a draft constitution for the entire French-speaking region of the former Prince-Bishopric would be launched. If accepted in both areas, the first step toward (re)uniting the two territories into a French-speaking canton of their own would have been taken. However, the plan was decisively rejected by the Francophone Protestants in Jura Bernois. Although 75% of the voters in Jura Canton supported the idea of receiving Jura Bernois, 72% of the voters in Jura Bernois voted against leaving Berne for Jura. Figure 2 displays the share of ‘yes’-votes across the two regions, North (Jura) and South (Jura Bernois), and across the 106 municipalities, the lowest level at which referendum data are available.

Figure 2 Distribution of ‘yes’-votes in the 2013 referendum (Jura and Jura Bernois).

Imagine for a moment that the referendum had passed and the two entities became united. The current majority in Jura Bernois, the French-speaking Protestants, would have become a religious minority in a reunited territory, while the French-speaking Catholics would have retained their majority position in both religious and linguistic terms. Clearly, then, unification would have been a better deal in this respect for Jura than for Jura Bernois, and this is likely part of the reason why the former voted 75% in favor of unifying, whereas only 28% voted for unification in the latter. That said, Jura Bernois is still a linguistic minority in Berne Canton, and therefore the question remains why an overwhelming majority in Jura Bernois revealed their preference to be ruled by a linguistically rather than a religiously alien group.

One reason for this might be that language is constitutionally protected in Switzerland, with its territorial borders fixed by both cantonal and federal law (Richter, Reference Richter2005: 159), in a way that religion is not (cf. Brubaker, Reference Buchanan and Faith2013). But even so, this would not explain intra-regional variation – of the 49 communes in Jura Bernois,Footnote 5 approval ranged from 2 to 55% (see also Table A1 in the Appendix). On the culturalist view, as Jura is French-speaking and Catholic, the municipalities of Jura Bernois that had more Catholics and French-speakers should favor seceding and joining Jura, as this would have resulted in native rule on both cultural dimensions. Further, if religion were more salient than language, then the two Catholic groups (French- and German-speaking Catholics) should be the most and second most in favor of joining Jura, followed by the two Protestant groups (French- and German-speaking). The Protestants should be the least in favor of joining Jura, as neither would want to be ruled by an alien cultural group. If language was more salient than religion, then we should observe the French-speakers, whether Protestant or Catholic, being more in favor of secession from Berne than the German-speakers of both religions. However, if neither language nor religion by themselves are important predictors of secession, but operate through political preferences and are constrained by ecological factors, then the models incorporating political and ecological factors should better predict the 2013 vote. This leads us to three primary hypotheses on cultural legacies, political preferences, and ecological constraints:

Hypothesis 1 Municipalities with more French-speakers and more Catholics are more likely to vote in favor of seceding from Berne.

Hypothesis 2 Municipalities with more statist political preferences are more likely to vote in favor of seceding from Berne.

Hypothesis3 Municipalities more proximate to the capital of Jura Canton (Delémont) are more likely to vote in favor of seceding from Berne.

After discussing our case selection in the next section, we operationalize and test these hypotheses.

Why Switzerland?

Before proceeding to the analysis, it is worth discussing the logic and limits of our case selection. Although there are important differences between internal and external secessions – especially, the greater amount of risk-aversion involved in an external secession (Nadeau, Martin and Blais, 1999) – there are three good reasons why testing our theory in this particular setting might be instructive. The first concerns the ostensibly clear distinction between internal and external secession, which we think has been sometimes exaggerated (Simeon, 2009; Gilliland, Reference Gilliland2012). On the one hand, secession in Western Europe rarely entails full independence. Most separatist movements do not seek total separation, but desire to remain in multinational governance units like the European Union, the European Monetary Union, or NATO (Sorens, Reference Sorens2012). On the other, federal states usually are characterized by autonomous regions that produce similar kinds of public goods that nation-states produce elsewhere. Such is the case for the Swiss Cantons: they have their own government, parliament, and courts as well as power over police, taxes, education, transport, health care, and social services, to name but the most important areas (Vatter, Reference Vatter2014). This significantly blurs the line between external and internal secession, and suggests that lessons learned from the study of internal secessions can speak to our understanding of external secessions (such as in Scotland).

Second, moving the analysis from the cross-national to the sub-national level increases the number of cases to be compared (Snyder, Reference Snyder2001). This is an important consideration for theory development, as there are only so many referenda on secession that have been allowed to take place (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014). Further, this kind of sub-national analysis affords researchers with considerable variation on the dependent variable (voting for secession) without having to control for numerous potential causal factors that differ across countries (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1971).

The third and final reason for studying the case of Jura Bernois is perhaps the most important theoretically. Overlapping identities in Jura Bernois – its majority population is French-speaking, as in the canton to be joined, but also Protestant, as in the canton to which it currently belongs – provide us with an excellent opportunity to investigate a crucial debate in the study of identity politics. In this case of cross-cutting cleavages, we can parse out the relative importance of language, ‘a pervasive, inescapable medium of social interaction’ (Brubaker, Reference Buchanan and Faith2013: 5), and religion, a key determinant of values and enduring political preferences (Jordan, Reference Jordan2014) and short-term voting behavior (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2014; Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Traunmüller, Freitag and Vatter2014). The people of Jura Bernois are faced with a choice between belonging to a political entity in which they are a linguistic minority or another in which they are a religious minority.

Analysis

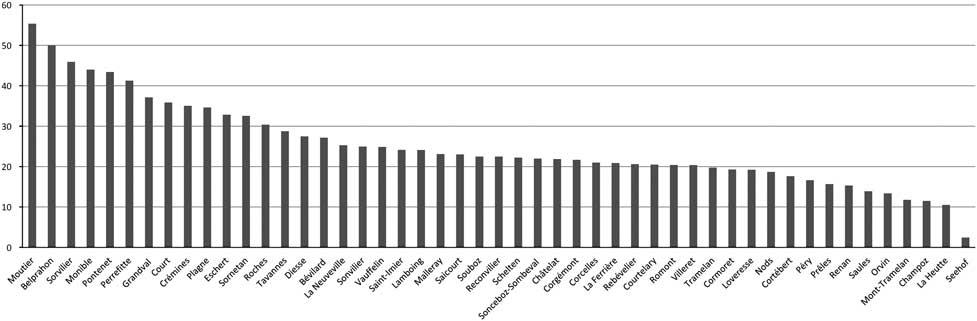

To test our theory as well as its alternatives, we have merged census with referendum and other political and socio-economic data. As the focus of this article is on secession rather than irredentism, our analysis will be confined to the political behavior in Jura Bernois. Hence, our dependent variable is the proportion of approving voters (yes-votes) in a given municipality in the November 2013 referendum, which is drawn from the official website of the Government of Berne.Footnote 6 As Figure 3 shows, there is considerable variation in the aggregate percentage in favor of unification in Jura Bernois, with one municipality – the regional capital, Moutier – narrowly approving and one other municipality – neighboring Belprahon – resulting in a tie. Data for all independent and control variables were aggregated to the level of municipalities as of November 2013 to make them compatible (for descriptive statistics, see Table A1 in the Appendix).

Figure 3 Share of yes-votes in Jura Bernois (2013).

To evaluate the straightforward culturalist explanation based on linguistic and religious homophily, we measure the proportion of French-speakers, Catholics, and French-speaking Catholics in each municipality. As Jura Bernois was deciding on whether to leave a largely German-Protestant Canton (Berne) for a predominantly French-Catholic one (Jura), on this view the more members of each of these groups in each municipality, the more it should be in favor of separation from Berne. To calculate the share of the respective groups in a municipality, we used the census data from 2000, the last year in which all residents were assessed by the BFS.

If cultural identities have enduring effects, and people carry their preferences with them to their new voting municipalities, then migration patterns should influence the vote. As French-Catholics should be most in favor of merging Jura Bernois with Jura, according to the cultural theory, we would expect those municipalities with the most French-Catholic immigration to be most in favor of joining Jura. To calculate increases in that group’s population size in each municipality, we subtracted census data from 2000 from 1970 census data (BFS, Reference Bieber1970, Reference Bieber2000).

To investigate the (economic) rationalist approach to secession, we examine pocketbook and social class issues. If people prefer to pay lower taxes and regard pocketbook issues as an important basis for their political decisions, then this should also be reflected in the 2013 referendum. To test this hypothesis, we rely on the local tax coefficients using the Government of Berne’s financial report (Finanzverwaltung des Kantons Bern, 2013). The local tax coefficient measures how much citizens in each municipality pay in addition to cantonal and federal taxes. Because local governments can autonomously decide on their tax coefficient, and because they are in competition with one another, coefficients are in principle set as low as possible. But only those municipalities that can afford to do so will have a low coefficient. Local tax coefficients are thus a measure of local wealth: the higher the tax coefficient, the poorer the local government. If this logic is accurate, we would expect that municipalities with higher tax coefficients should be more in favor of unification. Horowitz (Reference Horowitz1981, Reference Horowitz1985) has shown that poorer regions are early and frequent secessionists, whereas advanced regions are late and rare secessionists. By contrast, Ayres and Saideman (Reference Ayres2000) fails to find any relationship between economic differentials and secession. Sorens (2012) claims that the relationship depends on regime type – ‘in democracies, economically better off regions are more secessionist … in autocracies, this relationship could be weaker or non-existent’. However, as all the communes under investigation here are part of the same democratic polity, that last point can be ignored, for the moment.

To test the idea that subordinate social status will produce political salience of that cultural marker – and thereby shape the vote – we create a class variable for each of the four cultural groups (French-Catholics, French-Protestants, German-Catholics, and German-Protestants). We use Oesch’s (Reference Oesch2006) classification (cf. Oesch and Rennwald, Reference Oesch and Rennwald2010), which combines educational attainment, employment (ISCO codes), and employment status. The variable is then collapsed into three categories: upper (including Oesch’s large employers, self-employed professionals, technical experts, higher-grade managers and administrators, and sociocultural professionals), middle (petite bourgeoisie with and without employees, technicians, skilled crafts, associate managers and administrators, skilled office, sociocultural semi-professionals, and skilled service), and lower class (routine operatives, routine agriculture, routine office, and routine service). Classes are calculated on the basis of the 2000 census data. We then subtract the value for French-Catholics from that of German-Protestants in each municipality. Class-based arguments imply that municipalities where French-Catholics are subordinate to German-Protestants should express a greater desire to join Jura.

Finally, scholars have long emphasized how spatial factors, especially distance between peoples, shape network structures, identities, and preferences (Rokkan and Urwin, Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986; Lipset and Rokkan, 1990 [Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967]; Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Harmon, Werfel, Gard-Murray, Bar-Yam, Gros, Xulvi-Brunet and Bar-Yam2014), and this is also true in the case of Jura; indeed, it was the focus of the first systematic study of the Jurassien question (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1986). To measure distance, we calculated travel distance to Delémont (the capital of Jura) by car in minutes using Google Maps (2014). The variable was then recoded (46, the maximum, minus travel time) so that higher values denote proximity to Delémont. As mentioned above, the point of this variable is to capture the potential for communication as a facilitator for common ideas, norms, and preferences – and all of that with regard to the political capital of Jura Canton, the future ‘core’ if Jura Bernois had seceded.Footnote 7

Turning to the measurement of the indicators implied by our own theory, we emphasize how cultural identities (language and religion) shape political preferences, particularly in the domain of statism. To measure statist preferences, we use two indicators. The first is a measure of voting for left-wing parties in the last cantonal elections at local level (30 March 2014). Both the Social-Democrats (PS) and the Parti Socialiste Autonome were classified as left-wing parties.Footnote 8 Our second indicator of statist preferences is the share of people having voted in favor of gun control in the 13 February 2011 federal referendum. The popular initiative on which people voted that day, if approved, would have forbidden Swiss army members (technically, all Swiss men above 18 years) to store their personal weapon at home when not in service (BFS, Reference Bieber2011).Footnote 9 The right to bear arms is probably as sacred in Switzerland as it is in the United States, and thus a referendum on this issue is a good proxy for individual preferences for a larger or smaller role for government more generally [cf. Bühlmann and Caroni (2013) for a similar approach]. These political preferences, together with ecological factors, shaped the decision to secede. If true, then we should see municipalities in Jura Bernois having more statist preferences and those closer to the center of Jura being more in favor of seceding from Berne.Footnote 10

We adopt a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) approach because it captures our two-stage theoretical argument (Figure 1) better than a single-equation model.Footnote 11 SUR is a two-stage generalization of the general linear regression model (Zellner, Reference Zellner and Ando1962; Zellner and Ando, Reference Zellner2010). The first stage in an SUR is an ordinary least square (OLS) regression, the second uses the residuals from the first to estimate the elements of the matrix, Σ, via (feasible) generalized least squares regression, and the error terms are assumed to be correlated across the equations (Amemiya, Reference Amemiya1985: 198).

In the first stage, we predict political preferences as a function of cultural factors (language and religion), and in the second we predict the vote on secession as a function of political and ecological factors. The model can be written down in matrix form as follows (Zellner and Ando, Reference Zellner2010): y=Xβ+u, u

~

N(0, Ω ⊗ I), where N(

µ

, Σ) denotes the normal distribution with mean

µ

and covariance matrix Σ, ⊗ the tensor product, Ω an m×m symmetric matrix with diagonal elements

![]() $\{ {\rm \omega }_{1}^{2} ,...,\omega _{m}^{2} \} $

, and the off-diagonal ijth elements are ω

ij

, y′=(y′1, … , y′

m

),

X

=diag{X

1, … , X

m

},

β′

=(β′

1, … , β′

m

), and

u′

=(u′

1, … , u′

m

). Under the assumption of symmetric error distributions, the estimator produces unbiased coefficients and standard errors in small samples.

$\{ {\rm \omega }_{1}^{2} ,...,\omega _{m}^{2} \} $

, and the off-diagonal ijth elements are ω

ij

, y′=(y′1, … , y′

m

),

X

=diag{X

1, … , X

m

},

β′

=(β′

1, … , β′

m

), and

u′

=(u′

1, … , u′

m

). Under the assumption of symmetric error distributions, the estimator produces unbiased coefficients and standard errors in small samples.

Table 1 presents our main results. The first equation predicts political preferences on the basis of cultural factors, the second uses those political preferences, along with ecological factors, to predict the secession vote. Across all four model specifications, the results indicate that cultural factors (religion and language) help account for variation in political preferences over statism. These effects are strong and consistent across the models, and show that municipalities with more Catholics and French-speakers were much more likely than municipalities with fewer Catholics and French-speakers to vote for leftist parties promoting more statism.

Table 1 Seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) results of the cross-sectional analysis (Jura Bernois)

CDL=cultural division of labor; AIC=Akaike information criterion; BIC=Bayesian information criterion; RMSE=root mean square error.

SUR regressions; β coefficients with SEs in brackets.

*P<0.1, **P<0.05, ***P<0.01.

In the Jura vote equation, we find that these political preferences for statism (both in the form of left-wing voting and the referendum vote over gun control) are highly predictive. Those municipalities that voted more for leftist parties and more for gun control were much more likely to vote to secede from Berne and join Jura. Ecological effects were also important – municipalities closer to Delémont (the capital of Jura) expressed a much stronger desire to secede. This effect appears to be both additive and interactive. In models 1 and 2, we find evidence for an additive effect of proximity above and beyond the effect of political preferences. In models 3 and 4, we investigate an interactive effect, and find evidence for an interaction between proximity and left voting, but not for an interaction between proximity and gun control. In sum, models 1 and 2 and models 3 and 4 provide evidence for a significant joint effect on the decision to secede.

All of these models also provide reasonably tight fits to the data. R 2 numbers for the Jura vote equation all hover around 70% of the variance explained, and the figures for the first equation predicting the left vote reach a high of 55% (models 1, 3 and 4) and have a low of 47% (model 2). While Table 1 and Table A2 represent different approaches to estimating the parameters implied in the conceptual model, both methods bring us to a similar conclusion about the role of cultural, political, and ecological factors in shaping the decision to secede in Jura.

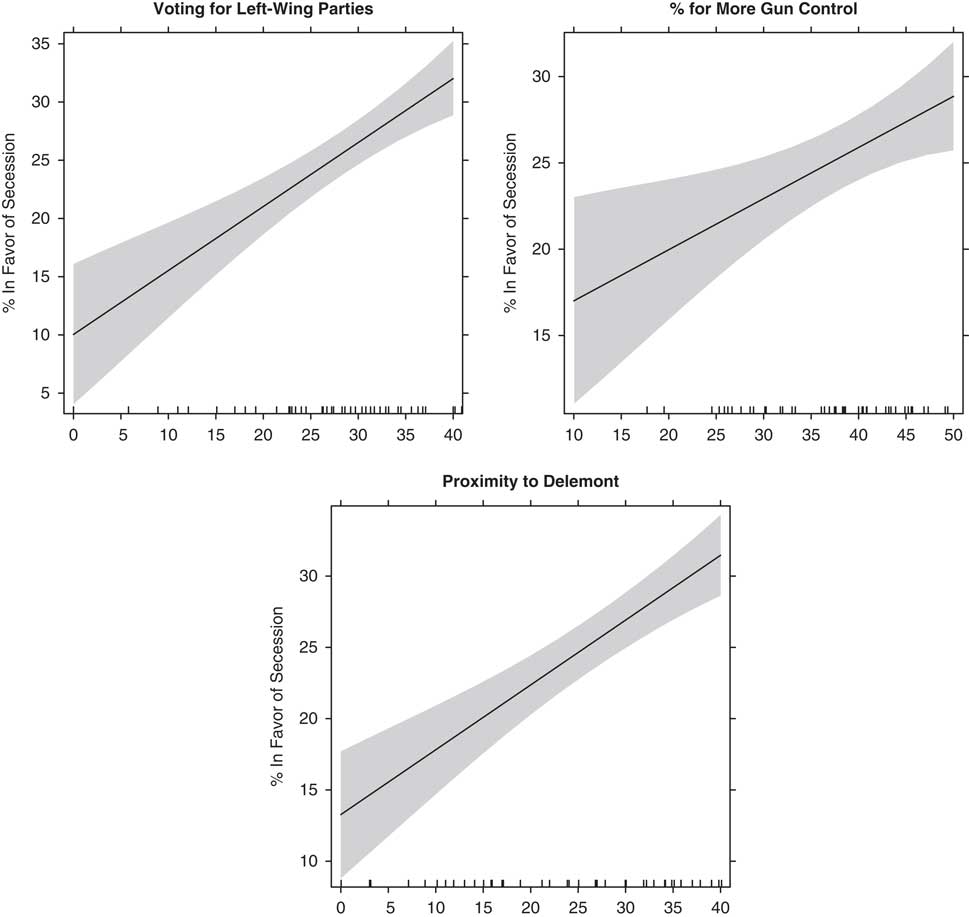

Figure 4 displays the marginal effects of these statist preferences, along with proximity, on the yes-vote. To get a sense of the range (Figure 2), recall that the minimum level of support for secession was 2% (Seehof), the maximum 55% (Moutier), and the average was 25% (La Neuveville). An increase in the proportion in favor of more state control over guns from 10 to 50% can be expected to increase the yes-vote from 17 to 30%, whereas an increase in the strength of left-wing parties from 0 to 40% leads to an increase in the yes-vote from about 10 to 32%. An increase in proximity to Delémont of 40 minutes is associated with an increase in the yes-vote from about 17%.

Figure 4 Marginal effects of left-wing voting (top), gun control voting, and proximity. The y-axis depicts the proportion of voters in favor of secession. The x-axis in the top left graph depicts the proportion of the population that voted for left-wing parties. The x-axis in the top right graph depicts the proportion of the population that voted in favor of more state control over guns. The x-axis in the bottom graph depicts the proximity to Delémont for each municipality.

To conclude, at least in Jura Bernois, the vote seems to have been about which alien ruler was preferable based on statist political preferences: a linguistically identical but religiously alien one (Jura Canton) or a religiously similar but linguistically alien one (Berne Canton). The citizens of Jura Bernois overwhelmingly voted to remain in Berne and not to join Jura. Why did Jura Bernois choose not to secede? We suggest that it was not because of religious homophily with Berne, nor because of purely pocketbook cost-benefit calculations, but because Berne offered better conditions for the realization of Jura Bernois’ political preferences – in this case, less statism.

What implications do these results have for cultural, rationalist, and structuralist accounts of separatism? This story of (non)secession, like many others around the world, has important elements of both the politics of identity and the politics of interest. Whereas a basic model with cultural variables alone (model 1 in Table A2) shows that municipalities with more French-speakers and more Catholics were significantly more likely to vote to secede, that model only explains 47% of the variance. Similarly, a straightforward rationalist model provides for about 28% of the explained variance, and a simple ecological model (not reported) explains 19% of the variance on its own. Our model, which shows that ecological factors and political preferences mattered for how people voted on secession, explains 67% of the observed variance – about 20% more than the next best model.

To investigate a further implication of our theory, we examine the extent to which the effect of political preferences mediates the influence of cultural identities. We conducted four Sobel tests (Reference Sobel1982) to quantify the possible mediation effects – that is, the extent to which the cultural effects of religion and language are mediated by our hypothesized mechanisms through statist preferences. Our results indicate that the strength of left-wing parties mediates a full 72% of the effect of language and 47% of the effect of religion on the vote. These very large mediation effects lend strong support to the notion that the effect of cultural identities is transmitted through political preferences over statism. The mediation effect of our second indicator of statist preferences – gun control – has a weaker effect: preferences for gun control mediate only 5% of the effect of language and 13% of the effect of religion on the vote. This could be because gun control merely captures one aspect of statism, namely a security vs. trust trade-off, whereas left-wing parties stand for a whole range of economic and progressive forms of statism – child care, tax breaks for the poor, education, infrastructure investments, environment, unemployment benefits, health care, and culture.

Finally, our results also indicate that geography matters. Proximity to the capital of Jura (Delémont) is statistically significant in all of the estimated models, which underpins the importance of ecology in this decision. But rather than regarding distance as a supporting factor of secession in itself, we think this result is best interpreted as a factor that enhances or undercuts the effect of political preferences. We now conclude by summarizing our findings and drawing more general implications.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the advantages of combining cultural, rational, and structural accounts of secession. It shows that each alone provides a less persuasive account than the alternative advanced here, and the empirical evidence bears this out. Specifically, in our case, Catholicism and French language confer distinct political preferences for more statism, which strongly predicted the yes-vote on the secession of Jura Bernois from Berne Canton. Adding ecological factors to this model improved it further. The 2013 referendum was less about identity as such, or about classic pocketbook issues, and more about whether Berne or Jura would be better able to satisfy Jura Bernois’ preference for less statism. On the evidence of the vote, Berne was preferred by 72% of voters.

What have we learned that is of general interest to scholars of secession? First, far from being mutually exclusive, cultural, rational, and structural logics can go hand in hand. Indeed, they need one another because culture can explain the origins of political preferences, through distinct cultural legacies, and structural factors constrain the effects of political preferences on collective action and decision-making, while rational choice can explain what people choose on the basis of those preferences. All else equal, people prefer to be ruled by their own kind, and if that is not possible they will chose the less alien of two alien rulers.

Second, the factors responsible for the political salience of different identities in multicultural societies may hinge on how these identities shape distinct political preferences for either more or less statism. That political preferences about statism trump cultural identity per se is a far cry from conventional expectations about the durability and salience of religious and linguistic distinctions in the literature on secession. In our case, identity only matters for secession via the specific political preferences that it entails.

Last, ecology matters in helping to reinforce or undercut distinct preferences among distinct cultural groups. Certain topographies facilitate contact with certain groups while obstructing relations with others. Thus, territory matters symbolically, by creating symbols of identification (‘our land’ – note that the flag of Jura Canton features seven stripes in memory of the seven districts of the former archbishopric, three of which form today’s Jura Bernois), as well as practically, by exposing people to the same news outlets whose circulation (newspapers) or reach (radio, TV) is necessarily limited; offering jobs within reasonable commuting times; and by creating ‘trust and codes of conduct, and shared organisational and technological cultures for collaboration and knowledge exchange’ (Lundquist and Trippl, Reference Lundquist and Trippl2013: 53).

If we try to generalize from this case, that Quebec is a French-speaking island in a sea of English-speakers certainly helped its claim for full independence – the referenda in 1980 and 1995 both failed, even if the second time the ‘no’ vote won by <1%. Given Quebec’s unique linguistic and religious legacies, overwhelmingly Francophone and Roman Catholic, a legacy of colonial settlement policies, a new referendum on the independence of Quebec may be merely a matter of time. Similar considerations on the actual content and level of public service delivery, and not so much the ethnic underpinning of the polity itself, have played a role in Scotland. However, as external and internal referenda are not completely comparable, our findings must await validation in a high-stakes external secession referendum.

In conclusion, secession and referenda on secession are on the rise in Europe. The case of Jura Bernois has highlighted many of the same issues that arise in other cases of secession, namely group identity, political preferences over the role of the state and geography, and the excellent empirical evidence in this study has enabled us to test rival explanations of secession in a way that is rarely possible. Nevertheless, assessing the external validity of the proposed theoretical model remains an important task for future research.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the Institute for Social Science Research at Arizona State University. The authors thank the Swiss Federal Office of Justice and the Swiss Statistical Office for giving them access to census data for 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000. The authors also thank all the participants of research workshops and conferences held in Berne, the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association in Washington, DC, a conference on ‘Self-Determination in Europe’ at the University of Berne, a workshop on ‘Ethnicity and Religion’, held at Arizona State University, the Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association, the Council for European Studies in Paris, the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture at Chapman University, and the Southwest Mixed Methods Workshop at the University of New Mexico. The authors would like to thank Liam Anderson, Marissa Brookes, Rogers Brubaker, Joann Buehler, Lenka Bustikova, Miguel Carreras, Lars-Erik Cederman, Bridget Coggins, Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, Jennifer Cyr, Lauren Duquette, Valery Dzutsati, Maureen Eger, Zachary Elkins, Tanisha Fazal, Béla Filep, Alain Gagnon, Anthony Gill, Sara Goodman, Ryan Griffiths, Chris Hale, John R. Hall, Eve Hepburn, Christine Horne, Mala Htun, Laurence Iannaccone, Jordan Kiper, Milli Lake, André Lecours, Julie Lucero, Devorah Manekin, John McCauley, Sara Niedzwiecki, Jami Nunez, Steven Pfaff, Philip Roeder, Aviel Roshwald, Andreas Schädel, Sarah Shair-Rosenfeld, Jared Rubin, Maria Saffon, Jason Seawright, Jason Sorens, Carli Steelman, Jody Vallejo, Mark von Hagan, and Carolyn M. Warner. For their hospitality and extensive discussions in Switzerland, the authors are grateful to Manfred Bühler, Marc Bühlmann, Emanuel Gogniat, Jean-Pierre Graber, Fabien Greub, Jean-Claude Rennwald, Daniel Rieder, and Maxime Zuber.

Appendix

Table A1 Variable descriptions

Table A2 Ordinary least square (OLS) results of the cross-sectional analysis (Jura Bernois)